Would Mexico "indirectly" pay for the wall?

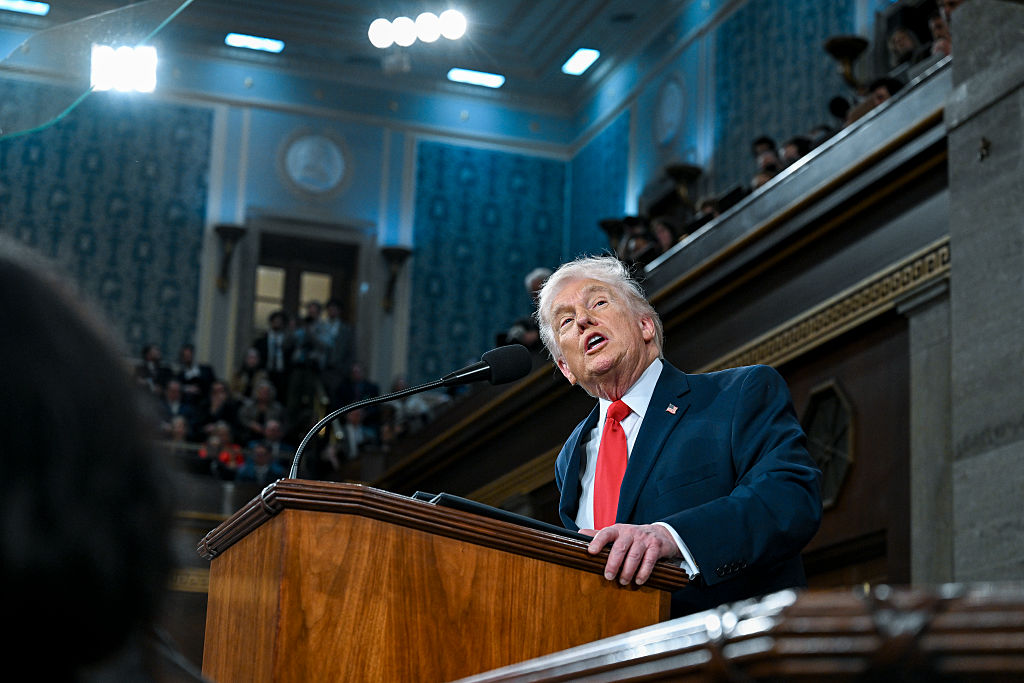

Mexico made it clear it won't pay for the border wall promised by President Donald Trump during the 2016 election campaign. Yet Mr. Trump keeps repeating the notion in various forms, most recently tying it to his newly renegotiated trade agreement with Mexico. The latest utterance came in his speech from the Oval Office last night.

"The wall will also be paid for indirectly by the great new trade deal we have made with Mexico," Mr. Trump said.

Fact check: False.

The new trade agreement reached last year, called the United States Mexico Canada Agreement, or USMCA, would replace the existing North American Free Trade Agreement, known as NAFTA, which has been in effect since the early 1990s. NAFTA eliminated most tariffs between the three signatories, with a few exceptions.

USMCA, which does little to change those eliminations, isn't yet in effect. That's because Congress still needs to ratify the deal (as do legislative bodies in Mexico and Canada).

In the U.S., USMCA ratification is far from certain and isn't likely to be taken up soon, given Democrats now control the House and the government remains partially shut down. Even if the new trade deal is enacted, it's not clear how funds in the U.S. Treasury would be earmarked to build Mr. Trump's wall.

Congress controls the purse strings

The president has previously implied that tariffs paid on Mexican imports could be used to bolster U.S. coffers and, in turn, be eventually allocated to pay for wall construction. That's also problematic: Congress drafts budgets and must approve any government spending.

"Donald Trump keeps repeating the ludicrous claim that somehow the revised NAFTA will fund his wall even though it remains unclear if the deal will be enacted," Lori Wallach, director of trade policy for advocacy group Public Citizen, said in a statement. "And if it is, the text does not include border wall funding directly nor would it generate new government revenue indirectly given it cuts the very few remaining tariffs, not raises them."

Tariffs are taxes paid at the border to the government in order to import goods and services into the U.S. for sale inside the country.

Any taxes collected into the U.S. Treasury that could be allocated for wall construction would still have to be approved by Congress, which at the moment remains at an impasse with Mr. Trump on that very topic. It's why the government is partially shut down.

Reminder: Companies, not countries, pay tariffs

Importers like Ford or Walmart pay these duties. They either swallow the cost or pass it along to consumers. That means it's often ordinary Americans who foot the bill for tariffs.

Mr. Trump's trade levies are designed to make certain goods more expensive for U.S. consumers, who in turn are likely to seek out lower-cost items made in the U.S. or from countries that aren't facing the higher tariffs.

For U.S. manufacturers, purchases are often raw materials, like steel, or finished and semi-finished parts, like seats for automobiles. The U.S. also imports food and commodities like grain and meat.

Take steel and aluminum. Mr. Trump's White House imposed tariffs on imported steel and aluminum last year. Because prices for imported metals are now higher, domestic producers have also been able to raise prices. And it's those increases that can get passed onto consumers for the finished goods.

When it comes to the USMCA, Mexico generally doesn't pay taxes on goods imported into the U.S. If there are tariffs, U.S. companies pay them. Higher tariffs can force a company to pass on that extra cost to the consumer.

Another theory is that the U.S. economy will be so good under the new agreement that the U.S. Treasury's coffers will swell, providing enough funds to pay the billions for Mr. Trump's wall. That's a lot of ifs, given the current impasse, experts have noted.

Bottom line: No matter how many times Mr. Trump says it, Mexico probably isn't paying for the wall, directly or indirectly, anytime soon. As things now stand, U.S. taxpayers would wind up with the bill.