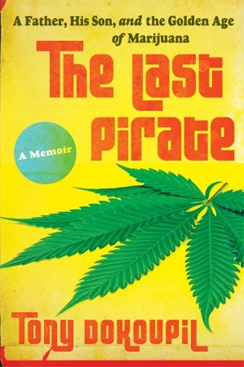

Book excerpt: "The Last Pirate"

The following is an excerpt from "The Last Pirate: A Father, His Son, and the Golden Age of Marijuana" by Tony Dokoupil (Random House). Reproduced with permission.

We hit Florida's Redland region to pick up a pair of collectible cars, which Mom loaned to the makers of "Miami Vice." We hit Long Island in pursuit of other coolers stuffed with cash and buried behind a house in the suburbs off I-495. But by far the richest prize was the one in Albuquerque, half a million dollars dropped into a hillside at my cousin's house. Sure, my mother loved the open road. She also knew you couldn't take more than $10,000 on an airplane without telling the authorities.

The man who buried the money began to amass it in his mid-twenties, selling a few baggies of pot. By his late twenties, he sold bricks of Mexican reefer every weekend, sometimes from the window of a Good Humor ice-cream truck. By the time he was thirty, he moved hundreds of pounds a month in the trunk of an old Buick, crisscrossing the mid-Atlantic states under the guise of delivering concert tickets. When he'd saved enough money, he flew to Miami, uninvited and alone, to knock on the door of a former car mechanic who imported tons of Colombian marijuana. He pitched himself as the most reliable black marketeer on the East Coast, "the best there is from box to box" (drugs to cash). He drove mobile homes packed with weed out of Key West, secured a fleet of pickup trucks from New England, and began to transport acres of South American mountainside up the I-95 "reefer express."

This was the late 1970s, I should add, which was also about the same time that he decided to start a family. He became a father the year he graduated to loads of ten and twenty thousand pounds of marijuana, transported on freighters and tugboats from the extreme northeastern edge of Colombia to sailboats near the Virgin Islands and ultimately to New York City wholesalers, vacation markets, and college towns along the East Coast.

In the years that followed, he buried nearly a million dollars, invested more than half a million more in a Yukon gold mine, and prepared the paperwork of escape, should he ever have to hit the reset as a card-carrying union welder and avid user of the Monmouth, New Jersey, library system. At his peak in the mid-1980s -- which was also the peak of the drug war, and an impossibly late date for pot smuggling -- he broke a weeks-long national dope panic, a drought that New York magazine dubbed "Reefer Sadness." In a single load he supplied enough marijuana to levitate every college-age person in America and send them sideways to the store for snacks.

By that time the Old Man, as he'd come to be called in the business, ran stateside operations for one of the most successful marijuana rings of the twentieth century. In careers that spanned the drug war from Nixon to Reagan, the Old Man and his friends slipped every major counter-narcotics operation, and came within one week -- one idiot with a lead foot and a Ferrari, in fact -- of getting off forever. In all they hauled and sold hundreds of thousands of pounds of marijuana, and the Old Man distributed at least fifty tons of it, an environmentalist's nightmare of plastic baggies, enough bud for thousands of part-time dealers, and millions of left-hand cigarettes, pinched and passed between friends.

At a certain point he grew into a "marijuana millionaire," as the press dubbed his kind, and the Old Man decided he needed to start acting more like a drug dealer. He bought a succession of inky-blue Mercedes sedans, a thirty-five-foot cruising yacht, and a hundred-acre swath of pristine Maine forest, dotted with lakes and capped by a dome of powder blue sky. He moved from Connecticut to Miami, the Wall Street of American weed, where he paid cash for a three-bedroom home south of the city and doted on the son he'd always wanted.

Together they toured the real pirate forts of the Caribbean and had a pillow fight beneath the gilded ceilings of the Plaza Hotel in New York. But perhaps their most blissful adventure came in late 1986, when family and friends gathered for a kind of retirement bash in the U.S. Virgin Islands. During the previous two years the gang had pulled off massive deals, netting the Old Man and his partner a million-dollar payday.

What followed was not your average cake-and-wine send-off but a weeklong bacchanalia culminating on an eighty-six-foot schooner near St. Thomas. The Old Man and his son were there, along with three other smugglers, distributors and dealers, two other kids, two unmarried mothers, and an escort turned girlfriend (because that's how dope dealers roll). Because he wasn't sure what pharmaceuticals were needed to fuel this exit to Eden, the Old Man packed everything he could sneak onto an Eastern Air Lines flight. Cocaine behind his belt buckle. Cocaine in film rolls. He brought a shaving satchel of rare herbs with heavy names like Oaxaca Red. He figured security wouldn't search a man traveling with his family, even if President Reagan had recently "run up the battle flag."

They sailed along, a dozen people partying on a boat designed to accommodate forty-nine. The parents drank Heinekens. The kids quaffed orange juice. Everyone ate lobster sandwiches and red snapper fillets. They napped on the white-pine deck and read Carl Hiaasen and Curious George in the cozy cabins below. The three kids -- ranging from six to twelve years old -- took turns steering the ship. And when they reached one of the area's lush, uninhabited cays, they slid off the stern and snorkeled right where they fell.

They swam to the shallows, where manta rays glided beneath them. And they nearly became fish food -- or so they were thrilled to think -- when a pair of plump, prehistoric-looking barracudas floated over for a look at their fathers' gold chains and shiny watches. When they went ashore, they fed hibiscus leaves and dahlias to wild iguanas and army-crawled beneath the decks of beachfront bars, where drunks and sun-stroked tourists dropped change between the floorboards.

Each day ended with the ocean smeared purple, the men holding their ladies close, and the kids clustered on the bow, dreaming of shipwrecks, pirates, and buried treasures. The world around was fenceless and so was the future. But the Old Man was restless in this paradise.

He had broken a cardinal rule of dealing and become an addict himself. Coke and hookers, mostly. He left the party early in search of both.

I know all this because the Old Man was my old man and when I was six I watched him go.

For more info:

- "The Last Pirate: A Father, His Son, and the Golden Age of Marijuana" by Tony Dokoupil (Random House); Also available in eBook and Unabridged Audio Download formats

- Follow Tony Dokoupil in Twitter