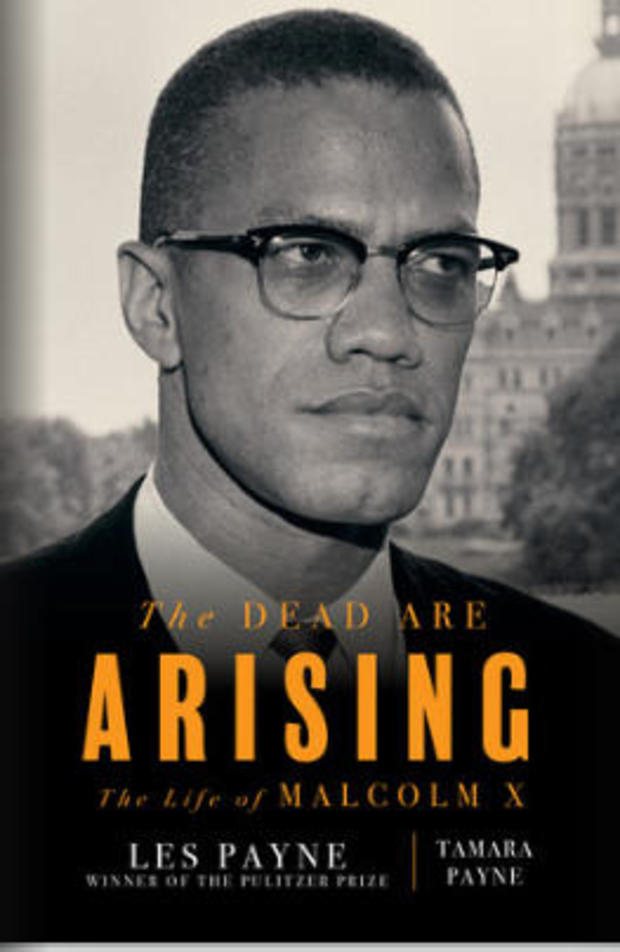

Book excerpt: "The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X"

A National Book Award winner for Best Nonfiction of 2020, "The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X" (Liveright) was begun nearly three decades ago by Les Payne, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and completed by his daughter, researcher Tamara Payne.

The book sets the story of Malcolm Little's life against the backdrop of American history, and through hundreds of hours of interviews the authors conjure a biography that rewrites the known arc of the human rights advocate's life and death.

Read the introduction to the book below.

Introduction

by Tamara Payne

When my father, Les Payne, began his research in 1990 for "The Dead Are Arising," Malcolm X was very much alive in the consciousness of the Black community. Walking down Harlem's 125th Street, you would hear Malcolm's emphatic voice resounding from the speakers of sidewalk vendors selling his speeches and you would see his countenance emblazoned on T-shirts.

This generation of hip-hop embraced Malcolm X because he spoke directly to them. His messages provided clear, direct analyses of what was happening around them in their communities. Point by point, he outlined how state-sanctioned racism is not new, but a continuation of the coordinated destruction of Black people in America. Malcolm changed the way they viewed themselves and gave voice to their struggles; numerous rappers and activists quoted Malcolm in their lyrics and interviews on radio and television.

Malcolm also changed the way Les Payne viewed himself. As a college student in 1963, he had heard Malcolm speak in Hartford, Connecticut. On that June night, my father came face-to-face with his own self-loathing. Malcolm X addressed the race issue head-on:

"Now I know you don't want to be called 'Black,' " he said. ... "You want to be called 'Negro.' But what does 'Negro' mean except 'black' in Spanish? So what you are saying is: 'It's OK to call me 'black' in Spanish, but don't call me black in English."

Later, in "The Night I Stopped Being a Negro," an essay that was first published in a collection titled "When Race Becomes Real," Payne wrote that he had entered "Bushnell Hall as a Negro with a capital 'N' and wandered out into the parking lot—as a Black man."

Born in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Payne had moved to Hartford with his mother and two brothers at age twelve:

I'd never met a White person, South or North, who did not feel comfortably superior to every Negro, no matter the rank or station. Conversely, no Negro I'd met or heard of had ever felt truly equal to Whites. For all their polemical posturing, not even Baldwin, Martin Luther King, Jr., or the great Richard Wright, with all his crossed-up feelings, had liberated themselves from the poisoned weed of Black self-loathing with its deeply entangled roots in the psyche.

The lightning strike of Malcolm's sword released the "conditioned sense of Negro inferiority" that was housed in the college junior's psyche. Hearing Malcolm's piercing analysis forced him to think about the Jim Crow South he was born into: remembering how he was told that Negroes were "just as good" as Whites, but seeing Negroes rise only to janitors, cooks, cotton pickers—not to landlords or owners of lumberyards. By the end of the lecture, Payne was irrevocably changed. "Whites were no longer superior. Blacks ... were no longer inferior," he wrote.

Always inspired by Malcolm X, Payne would reread his dog-eared copy of the "Autobiography" every five years. So he was naturally curious when his high school buddy Walter O. Evans, who had become a successful surgeon in Detroit, introduced him to Philbert Little, one of Malcolm X's brothers. Payne discussed this meeting with Gil Noble, a friend and fellow journalist who at the time hosted the weekly Sunday show "Like It Is" on WABC-TV in New York. In addition to his work as a renowned broadcaster, Noble was an admirer of Malcolm X. Every year, he dedicated episodes of "Like It Is" to the life and assassination of Malcolm X. Noble suggested that Payne also meet Wilfred Little, Malcolm's oldest brother and best friend.

At the time, Payne was an editor at Newsday, a daily newspaper on Long Island. He had won a Pulitzer Prize in 1974 as part of a reporting team investigating the international flow of heroin from the poppy fields of Turkey, through the French connection, and into the veins of New York drug addicts. He was renowned for his investigative persistence and his skill in obtaining the truth from reluctant sources. As he often told his three children—Jamal, Haile, and myself—he could not abide the phrase "We may never know."

After sitting down in Detroit with the two siblings, he was shocked to realize how much he did not know about the man whom he had admired and studied. For such a persistent seeker of the true story, the fact that so much remained unknown about Malcolm proved irresistible. It set my father on a journey that would last twenty-eight years, until his untimely death in 2018.

Excerpted from "The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X" by Les Payne and Tamara Payne. Copyright © 2020 by the Estate of Les Payne. Used with permission of the publisher, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

For more info:

- "The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X" by Les Payne and Tamara Payne (Liveright), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon and Indiebound