Book excerpt: The power of "2001: A Space Odyssey"

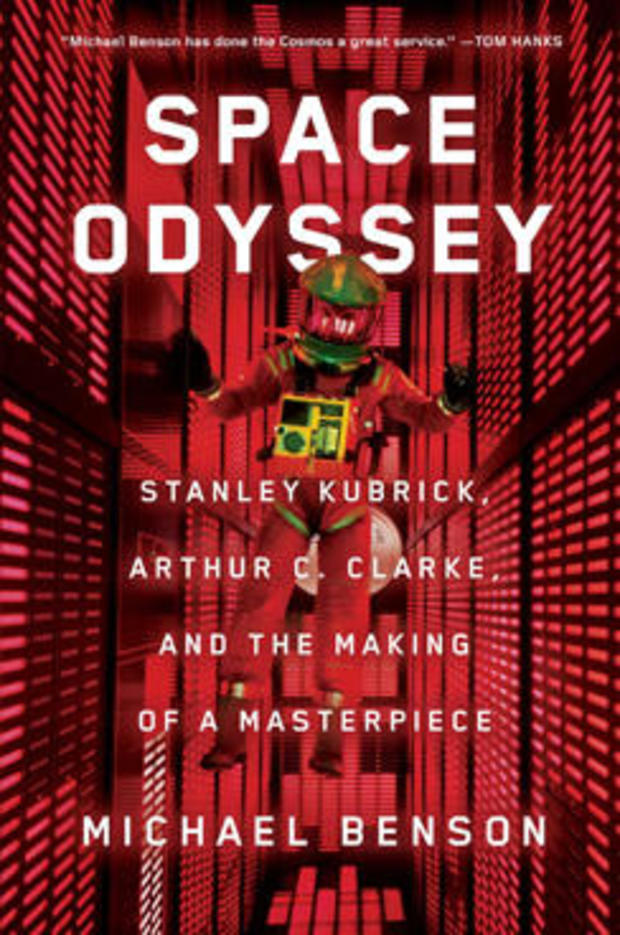

In this excerpt from "Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece" (Simon & Schuster), author and "2001" fan Michael Benson writes about his lifelong fascination with Kubrick's masterwork, and his discussion with co-screenwriter Arthur C. Clarke about the enigmatic film which has inspired generations of moviemakers and movie fans.

Don't miss Susan Spencer's interview with Michael Benson on CBS' "Sunday Morning" May 27!

My own lifelong engagement with "2001" started in the spring of 1968 at the age of six. My mom, a confirmed Clarke fan, took me to an afternoon matinee within weeks of the film's premiere. Whether it was in Washington (where we then lived) or New York (as I remember it) is unclear. While I was already excited by the jump into space as then best represented by the Apollo program—which had already launched two of its towering Saturn V Moon rockets on unmanned test flights—it was no preparation for my first exposure to such a powerfully ambiguous, visually stunning work.

At six, of course, your receptors are about as open as they'll ever be, and I consider myself fortunate to have seen the film at that age. The Dawn of Man prelude was both riveting and disturbing, and the mysterious appearance of the monolith, accompanied by the unholy keening of György Ligeti's "Requiem," reverberated in my childish imagination with almost overpowering overtones of mystery, wonderment, and horror. The ecstatic discovery by the lead man-ape that a heavy bone could be used as a weapon, which Kubrick conveyed with a wordless cinematic assurance, needed no explanation and didn't even require conscious understanding. It spoke in its own language; as with much of the rest of the film, the authority and power of the images themselves didn't necessitate literal comprehension.

The lunar, spaceflight, and space-walk scenes were mesmerizing. The effects of zero gravity on the human body were conveyed with utterly convincing realism. Bowman's methodical lobotomization of HAL couldn't have been more disturbing and frighteningly strange. And the film's abstract "Star Gate" sequence, which led to Bowman's multistage transformation into an elderly man, seen on his deathbed in a phantasmagorical hotel room—and then finally his transformation into that ethereal floating fetus—was spellbinding.

Much of it was also incomprehensible, however, and afterward, I trailed my mom across the pavement of whichever city it may have been, exhausted by a surfeit of wonderment and squinting in the dazzling late-afternoon sunlight. "But what did it mean?" I wailed. "I don't know!" she replied, to her great credit. Mom was always honest with me—and is to this day.

Much later, I grew to understand that "2001"'s power over me then and thereafter came about at least partially due to personal circumstances. As the child of foreign service parents, I had already lived in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, as well as Hamburg, West Germany—two countries that no longer exist. Although an American by birth, my world was the world, and my nascent identity was global by default. What I'm getting at is that I believe that even at the age of six, I grasped, in a preconscious, precocious kind of way, that we live in a complex world surrounded by multiple contradictory cultures, perspectives, and ways of being. Unfortunately, an unwanted side effect of changing countries so regularly can be a sense of not belonging to any one place—the so-called third-culture syndrome of the expat kid.

It would risk both cliché and oversimplification to suggest that "2001: A Space Odyssey" helped me be at home in the world. But there's no doubt that as with any major work of art that has a decisive impact on a person, it did so for a very good reason. As the years passed, I saw the film again many times, and it always struck me as an extraordinarily prescient account of the human situation in a mystifyingly grand, seemingly indifferent cosmos. The visual magnificence and uncompromising artistic integrity of Kubrick's and Clarke's achievement made the accuracy of its individual details beside the point. In the decades since the film's release, paleoanthropologists have largely discredited its depiction of the transition from vegetarian man-apes to carnivorous killers, which was based on the work of paleontologist Raymond Dart. And, at least to date, we don't have credible evidence of even microbial life beyond Earth, let alone superpowered extraterrestrial interlopers with an uncanny interest in our evolutionary progress. (Of course, the surest sign that intelligent life exists out there may well be that it hasn't come here—as Clarke used to joke.)

And, unfortunately, "2001"'s vision of the Moon and planets being colonized by human beings simply hasn't come true—or, at least, not nearly in the way its authors had envisioned. The film was made when NASA's budget was at its peak, so their extrapolation is understandable. (Clarke even predicted to Kubrick, "This is the last big space film that won't be made on location.") In fact, no human being has ventured beyond low Earth orbit since the return of the last Apollo crew from the Taurus-Littrow Valley on the Moon in 1972, just four years after the film's release. Since then, true space exploration has been conducted exclusively by automated spacecraft. But even if we consider HAL's attempts to kill off Discovery's crew and continue on to Jupiter without pesky human interference as predictive of these circumstances (and it's a valid interpretation), the film's deviations from literal accuracy are beside the point. Like Joyce—like Homer himself—"2001"'s authors were crafting a story. As a fiction, it created its own reality and demands to be viewed within that frame.

In any case, Kubrick's and Clarke's portrayal of twenty-first-century humanity suspended within an evolutionary trajectory spanning millions of years, and their placement of that story within a universe potentially filled with ancient civilizations—not to mention their depiction of human beings as desensitized parts of the machinery they've created, and their evocation of an artificial intelligence brought into being through human genius, yet driven through human error into conflict with its makers—it all had, and still has, a perspicacious, even ominous ring of truth to it. Ask not for whom the monolith tolls.

• • •

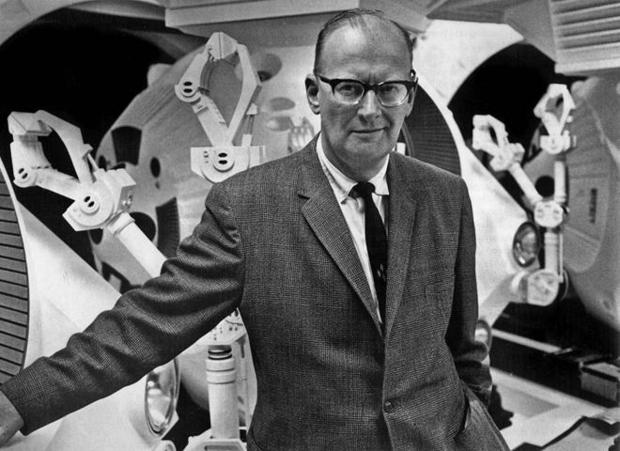

I never met Stanley Kubrick, though I've had the privilege of spending many entertaining hours in discussion with his widow, Christiane, at their impressive estate and manor in Childwickbury, a hamlet north of London. I did get to know Arthur Clarke during the last decade of his life, and visited him three times in Sri Lanka, the last with my family in tow. When I first met him, in the year 2001, no less, he was already confined to a wheelchair due to a progressive neurological ailment called post-polio syndrome, but I found him to be an alert, cheerful, wickedly humorous presence, always up for an in‑depth discussion and gratifyingly willing to mobilize a small motorcade and show me around the southern part of the island. We discussed "2001: A Space Odyssey" at some length, and though most of what he had to say he'd already published in one form or another, he would occasionally come up with an unexpected glint of insight that has proven valuable in the writing of this book. It was Clarke, for example, who told me about Kubrick's instant antipathy to his friend Carl Sagan—something I might not have known otherwise.

At one of our first meetings, I had the temerity to ask who had written perhaps "2001"'s most powerful scene: the one where Dave Bowman, having forcibly gained reentry to his ship, proceeds to HAL's Brain Room and deprograms the computer. "Who do you think wrote it? I did!" he boomed in mock indignation. While I accepted his statement, the reason I asked—and I told him this—was that the sequence has a chilly intensity that I recognized as more Kubrickian than Clarkean. In fact, as with any good collaboration, the truth lies somewhere in-between. While Clarke appears to have conceived of the scene up to a point—or at least put forward the Cartesian proposition that an artificial intelligence is alive and therefore can be hurt—Kubrick did, in fact, write it, as he did most of "2001"'s dialogue. Of which there isn't much: the film has less than 40 minutes of spoken words in its 142 minutes of running time. You could say that in this case, Kubrick handled the lyrics and Clarke the tune—something the latter wasn't particularly prepared to adjudicate more than three decades later to a whippersnapper such as myself, understandably enough.

Of course, this presents a paradox. Clarke was the writer and Kubrick the filmmaker, so one might be excused for assuming that what words there are in "2001" must have chattered from his portable typewriter at some point between 1964 and 1968. Not so. Almost every scene was rewritten multiple times by the director during live action production, which—if we exempt the wordless Dawn of Man sequence—extended for just over six months, from late December 1965 to mid-July 1966. (The prehistoric prelude was shot in the summer of 1967.) And throughout the film's production, but in particular during editing, Kubrick's instinct was to remove as much verbal explication as possible in favor of purely visual and sonic cues. Much to the consternation of his collaborator, this included Clarke's voice-over narrations, which were originally intended to frame the story.

Kubrick thereby lifted away what would have been a superstructure of overtly stated truths. He did so without necessarily losing them altogether; they were now implicit rather than explicit. The result was a masterwork of oblique, visceral, and intuited meanings. "2001"'s conscious deployment of a mythological structure, its insistence on first-person experiential cinema, and the inherent opacity of its "true" messages permitted every viewer to project his or her own understandings on it. It's an important reason for the film's enduring power and relevance.

Finally, "2001: A Space Odyssey" is about our situation as creatures conscious of our own mortality, aware of inherent limitations to our imaginations and intellectual capacities, and yet perpetually striving for more exalted states and higher planes of being. And that's where it best reveals itself as a profoundly collaborative work. While obviously Kubrick's film, it's Clarke's as well, and represents a grand synthesis of themes the writer had been working on for decades. These include the rebirth of the species into a transcendent new form. While it took Kubrick's brilliance to recognize it and make it so, it's no accident that the single most optimistic vision in his entire body of work—"2001"'s Star Child—was Clarke's idea. The alliance between these two gifted, idiosyncratic men during the four years it took to bring "2001: A Space Odyssey" to the screen required great patience and sensitivity on both sides. It was the most consequential collaboration in either of their lives.

From "Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece," by Michael Benson. Copyright 2018 by Michael Benson. Reprinted with permission.

For more info:

- "Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece" by Michael Benson (Simon & Schuster); Available via Amazon

- "2001: A Space Odyssey" is now playing in re-release nationwide in 70mm engagements (Official site)

- "2001: A Space Odyssey" (novel) by Arthur C. Clarke (Ace); Available via Amazon

- "2001: A Space Odyssey" (in70mm.com)

See also:

- "2001: A Space Odyssey" returns to theatres in 70mm (CBS News, 05/29/18)

- "2001: A Space Odyssey" turns 50 (CBS News)

- Reissue poster

- Bold vision of "2001: A Space Odyssey" commemorated ("CBS This Morning," 07/09/14)

- "2001" Original Cinema Program