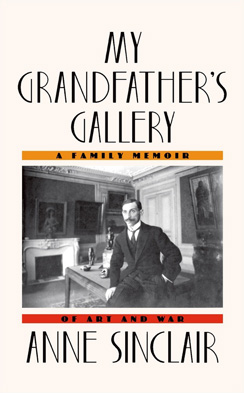

Book excerpt: "My Grandfather's Gallery"

Anne Sinclair, a journalist considered the Barbara Walters of France, was born in New York but raised by her parents in France, the country that Sinclair's grandfather, Paul Rosenberg, had been forced to flee during World War II.

An art collector, Rosenberg was the exclusive dealer for Pablo Picasso long before Picasso (or other modern artists like Braques or Matisse) became international superstars.

In "My Grandfather's Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War" (Macmillan/Farrar, Straus & Giroux), Sinclair tells the story of how Rosenberg, who was Jewish, was forced to flee France in 1940 after the Nazis confiscated his gallery and much of his art collection.

What follows are excerpts from the book's introduction.

Watch Erin Moriarty's interview with Anne Sinclair on "Sunday Morning" March 1

Introduction

A day of rain and demonstrations, early 2010.

My neighborhood has been closed off by the police, the streets are jammed around the Bastille, and I am a prisoner in a car that I can't simply abandon in the middle of the road. At last, reaching a CRS (state police force) barrier blocking off the Boulevard Beaumarchais, near the Place de la Bastille, I wind down my window and ask the soaked cop if I can slip by like the other local residents. "Your papers," he says wearily. I've just moved in, and I haven't got a driver's license or any ID with my new address on it. He's sorry, he can't take my word for it. I need proof of my new place of residence. I can't get home.

A little while later I write to the office in Nantes that issues copies of birth certificates to French citizens born abroad. When it sends me the document, I go to the police station nearest to my house, quai de Gesvres, armed with the necessary papers: the birth certificate they have asked for as well as my recently renewed identity card, valid for another seven years.

A long queue. I take my ticket and wait for an hour and a half, long enough to look around at the people who have come to pick up IDs or passports and to hear the overworked clerks bluntly questioning the assembled supplicants. "Madame, I must know whether or not you are from Guadeloupe!" an old woman is asked in a tone that sounds a lot harsher than if she were asked, "Are you originally from the Loire-Atlantique?"

At last it's my turn. I take the papers out of my file. It is then that a man behind the counter is astonished to discover that I was born abroad. I tell him that since I was born in New York, my administrative papers had to come from the offices in Nantes. He then asks for my parents' birth certificates. I spare him their story: how they met after the war when my father had been demobilized from the Free French forces. I refrain from explaining that I was born in America by chance and stayed there for only two years before coming to France to spend the rest of my life here because my father couldn't find a job. I'm an inch away from trying to find excuses for being born outside French territory.

On the other hand, I am feeling a bit surprised by his insistence on asking for my parents' birth certificates. Besides, I add that on mine -- look, monsieur -- it clearly states that Anne S. is the daughter of Robert S. and Micheline R., both born in Paris, and that I'm therefore what's known as French by affiliation. I also hand him my identity card, issued three years ago and valid until 2017, which means that it's up to the administration to demonstrate that it is fraudulent, should it have any suspicion.

But he persists: the papers are necessary; there are new directives dating from 2009 for any citizen wishing to prove his "Frenchness."

"Are your four grandparents French?" asks the man behind the counter.

Fearing I may have misheard, I ask him to repeat the question.

"Your four grandparents, were they born in France, yes or no?"

"The last time people of their generation were asked this kind of question was before they were put on a train to Pithiviers or Beaune-la-Rolande!" I say, my voice choking with rage, as I name the French camps where Jews were locked up by the French collaborating police before being deported by the Nazis to the death camps.

"What? What train? What are you talking about? I must repeat that I need that document. Don't come back until you have it in your possession."

He dismisses me abruptly, pushing toward me my file, which by the purest coincidence is yellow, the very color of the star Jews had to wear on their clothes.

No point in giving a history lesson to a clerk to whom the Vichy laws mean nothing and to whom no one responsible for the new regulations has taken the time to explain that there are unfortunate turns of phrase, reminiscent of more troubled times, that might be best avoided.

I leave, more hurt than angry with this draconian desk clerk, feeling that my birth is somehow suspect, as if there were two categories of French people, some more French than others. I'm also thinking about the absurdity of this situation, given that other officials, years ago, unaware of the doubts surrounding my origins, appointed me the model for their statue of Marianne, the symbol of France, worthy to take pride of place in their town halls. This isn't just an administrative bore. It's the revival of an unhealthy debate about national identity that has been poisoning France in the last few years.

..................

My mishap at the police station was pretty harmless in the scheme of things, but the questioning of my identity brought a tidal wave of family memories surging forward. For years I had refused to listen to the stories of the past told over and over again by my mother. Not out of a desire to reject my family, but the story of my maternal grandparents, even though I thought I knew it, never felt as if it belonged to me, as if it related to my life. It even bored me a bit. What I liked was politics, journalism; my father's world rather than my mother's. My father, who had joined the Free French in the Middle East during the war; my father, who, under the name of Jacques Breton, had delivered editorials on Radio Beirut on behalf of General Charles de Gaulle; my father, so proud to show me the agency dispatch in which Joseph Goebbels had condemned him to death and railed against "the Jew Sinclair"; my father, having returned to Paris after the liberation, paying a final visit to his own father, who had been seriously ill since Drancy. Even though my father himself built an industrial career as a business executive far from my own areas of interest, I felt closer to the war stories he recorded in his notebooks than I did to my mother's side of the family, which lived under the shadow of my art dealer grandfather, who had died when I was only eleven years old. In short, I secretly felt I was on the same side as "My Father the Hero," who gently mocked "My Mother Who Sat Out the War on Fifth Avenue."

My father, Robert Sinclair, who was called Robert Schwartz throughout his youth, was sent to the front in 1939 as a thirty-year-old soldier, on meteorological duty. He was stationed at a border post (might it have been the Maginot Line?) and played chess, one move per day with a colleague who had been sent to a different strategic location, taking advantage of their daily call to compare weather conditions on the front. They sat there and waited for the enemy, who never came because they had decided to avoid that predictable line of defense. (I like to imagine him moving his rook or his knight, occasionally sticking his hand outside and saying, "It's raining," to his friend, who would reply, "Here too!") When he was finally demobilized, he returned to Paris and, like many others, wept at the sight of flags bearing the swastika fluttering over the Champs-Élysées. He remembered the day he had stood there with his mother, on November 11, 1918, applauding Marshal Ferdinand Foch's troops as they celebrated the victory of the First World War. He was just a nine-year-old boy, but he told me he knew that he was destined to enlist from that time.

Unaware of the networks that would have enabled him to pass through England, he managed to reach the United States via a series of complicated routes, and it was there that he enrolled in Free France, which ultimately sent him to Damascus, Beirut, and Cairo. Before boarding the ship bound for the Middle East via the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, all lights extinguished so as not to alert the enemy, he was told that the Germans were aware of the surnames of French officers who had enlisted with de Gaulle and whose families had stayed in France. To protect his relatives, he was compelled to change his name. Wanting to retain his initials, he opened the New York City phone book to the letter S and stumbled upon the name Sinclair, perhaps no more unusual in the United States than Martin or Dupont in France.

I have always been a bit irritated with him for wanting to keep the name Sinclair and then legally adopting it as his surname after the war. It meant losing a part of our identity. But he had earned a name for himself under that nom de guerre; he bore it proudly and probably wanted to allow his descendants -- me, as it happened -- to avoid the dangers that a Jewish name had inflicted on his family. This was not unusual among those traumatized by the war in the years that followed the liberation, but I confess that I've always experienced it as a sort of denial. That's probably why I laid claim to my Jewish identity very early on. And why I've been distressed by those who, playing with proportional representation, allowed the extreme right Front National (FN) to exist politically in France. It's why I fought bitterly against the media access so generously granted to the FN in the 1980s and why for ten years I refused to have Jean-Marie Le Pen on my television program, 7 sur 7, which was a discussion of the previous week's political news. The pointlessness of this battle became apparent on April 21, 2002, and in the years that followed, when Le Pen came in second in the general election, the consequences of which we are still living with today.

So much for rummaging around in the cardboard boxes of family archives. As I went through all those random papers, I eventually came across my original birth certificate, rather than the copy generally required by the administrative services. What would the clerk at the prefecture, who prompted this book, after all, have said if he had seen that I had been born Anne Schwartz, dite Sinclair, and that my name was only officially changed in 1949, when I was one year old?

In my youth I was more receptive to the story of my paternal grandparents, who had stayed in France, than I was to the fate of those who, pursued by the Nazis, had managed to flee and were then dispossessed, plundered, and stripped of their nationality. Besides, I wanted to build my own life, preferring television to art galleries, the public life to the artistic one, old newspapers to old paintings.

In 2006 my mother passed away. And as always after the death of a parent, you're struck by all the things you've neglected to ask or didn't want to know, whether out of laziness or weariness at hearing the same stories again and again. In my mother's flat, I emptied cupboards crammed with dusty memories: old keys, outmoded furs, family photographs, and stacks of papers that had accumulated over the course of decades.

Then I turned sixty and happened to spend a few years in the United States, a country that constantly brought me back to my childhood and to the part of the family that had sought refuge there. And here were the French authorities, playing with dangerous ideas, reminding me that French nationality can't be taken for granted even if you've had it all your life. How fragile it is to those who bear it and how inaccessible to those who wish to lay claim to it. And reminding me that it wasn't the first time this had happened in my family.

I realized I hadn't even had time to unpack the boxes from my mother's apartment, which I'd stacked in a closet. They were full of letters and old files that I'd picked up without even giving them a thought. Suddenly unable to contain my curiosity, I plunged into the family archives, in search of the story of my past. To find out who my mother's father really was: my grandfather Paul Rosenberg, a man hailed as a pioneer in the world of painting, of modern art, who then became a pariah in his own country during the Second World War. I yearned to fit together the pieces of this French story of art and war.

I am the granddaughter of Paul Rosenberg, a gentleman who lived in Paris and who owned a gallery at 21 rue a Boétie.

"My Grandfather's Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War" by Anne Sinclair; Translated from the French by Shaun Whiteside. Published by Macmillan - Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Copyright © 2012 by Éditions Grasset & Fasquelle. Translation copyright © 2014 by Shaun Whiteside. All rights reserved

For more info:

- "My Grandfather's Gallery: A Family Memoir of Art and War" by Anne Sinclair; Translated from the French by Shaun Whiteside (Macmillan/Farrar, Straus & Giroux); Also available in Trade Paperback and eBook formats