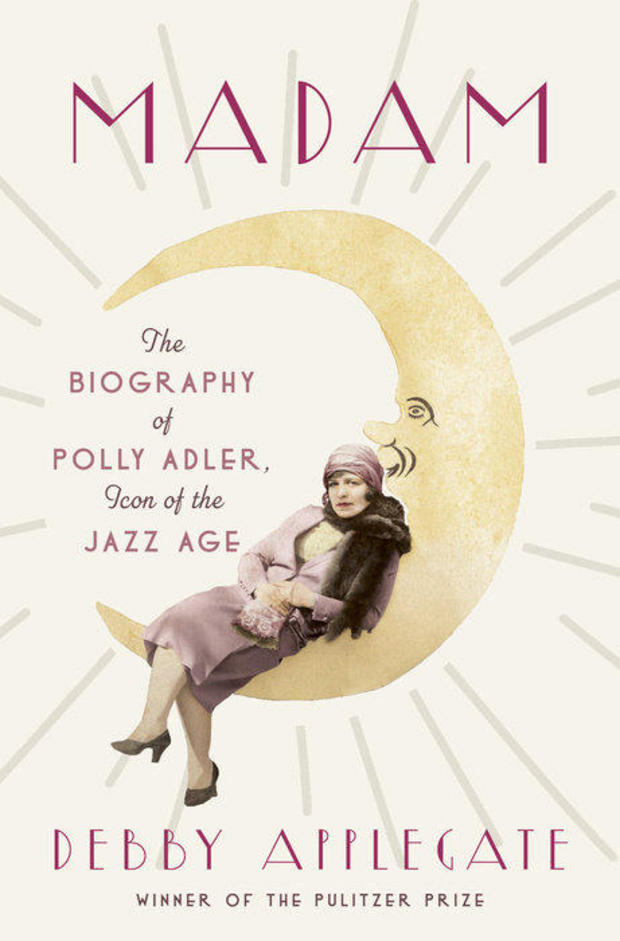

Book excerpt: "Madam," the story of renowned brothel owner Polly Adler

In "Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age" (Doubleday), Debby Applegate, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of "The Most Famous Man in America," traces the rise and fall of one of the Prohibition Era's most renowned figures: Polly Adler, Manhattan's most successful brothel-owner, who catered to politicians, celebrities, and the mob.

Read the excerpt below, and don't miss John Dickerson's interview with Debby Applegate on "CBS Sunday Morning" November 7!

Whore is a word that jars the ear and tastes bitter on the tongue. The English language abounds in more polite, poetic, and precise terms to describe a woman who trades sex for money: prostitute, sex worker, lady of the evening, working girl, fallen woman, call girl. Many more are unapologetically rude: hooker, gash, c**t, and piece of hide were all commonly heard in the dives of New York after the Great War.

Women who made a business of sex in those days often turned up their noses at the term prostitute, preferring to call themselves hustlers, party girls, or regulars. But everyone in the sex trade used the word whore. "In those days prostitutes weren't called chippies or tarts or call girls or any other fancy names," remembered the columnist Danton Walker. "They were known, quite properly, by the Biblical name: whores, and their establishments were called whorehouses." It was, after all, one of the world's oldest words, used to describe the world's oldest profession.

No one meeting Pearl Adler on the street would have taken her for a fallen woman, let alone the proprietress of Manhattan's most renowned bordello. "She was homey," remembered the journalist Irving Drutman; "one would have placed her, and how mistakenly, as the ubiquitous mama in a family-run delicatessen." Only twenty-seven years old, give or take, and tiny—barely five feet tall in her highest heels—she had a kewpie doll face and a sweet smile that revealed a girlish little gap between her two front teeth. She dressed conservatively in beautifully tailored clothes, often of her own design. Her hair was fashionably bobbed at the neck, her hands tastefully manicured. No ankle bracelets, heavy makeup, or the jungle-red nail polish associated with women of the night. Her jewelry was a tad showy and she had a well-known weakness for mink coats, but no more so than any ambitious Manhattan gold digger.

It was easy to underestimate her, at least until she opened her mouth. She was blessed with "the voice of a longshoreman" in the words of Oscar Levant—naturally husky and roughened by cigarettes, scotch, and a thousand late nights. It was so deep that telephone callers frequently mistook her for a man, much to her annoyance. "I can still hear her hollering over the phone, 'This is Polly Adler, God damn it. Stop calling me mister,'" remembered one friend with amusement. Thirteen years after fleeing the Jewish Pale of Russia, she still spoke with Yiddish inflections, generously sprinkled with immigrant malapropisms and Broadway slang.

Not everyone liked her, of course. Rival madams didn't care for her upstart ambitions. Some of the Broadway butterflies who worked for her chafed at her ban on drugs and pimps, her insistence that they go to bed with whoever came through the door, and her frequent lectures on social etiquette. Men who were touchy about their own social status often took comfort in belittling her. "I knew Polly Adler," sniped the famously combative writer John O'Hara; "she was a noisy bore, who looked like Mike Romanoff in drag" (a reference to the infamous Russian-born con man–turned–Hollywood restaurateur). She'd been snubbed in public more times than she could possibly remember, even if she had wanted to.

Nonetheless, her fans outnumbered her foes. Slumming intellectuals and Broadway bohemians were tickled by her blunt realism and lightly louche wisecracks. Fellow Jews from the old country found her house haimish, a cozy home away from home. Many in the underground gay community—both male and female—found her parlor a retreat where they could relax and be themselves. Everyone, from Park Avenue aristocrats to Lower East Side hooligans, appreciated her ironclad discretion.

"Polly Adler was one of the most fascinating females I ever knew," recalled the playboy songwriter Jimmy Van Heusen. "How the hell do you explain why you like someone? Polly was warm and funny, smart and gutsy and fun to be around. We liked each other and didn't take the time to think about it much."

There were plenty of other madams in Manhattan, but none of them seemed to have the combination of charisma and brains that made Polly one of the "authentic Big Shots" of the town, as one Broadway columnist dubbed her.

Polly was more modest. "I was a creation of the times, of an era whose credo was: 'Anything which is economically right is morally right'—and my story is inseparable from the story of the twenties," she wrote later. "In fact, if I had all of history to choose from, I could hardly have picked a better age in which to be a madam."

She'd opened her first brothel in 1920—a self-styled "house of assignation" in a two-bedroom apartment across from Columbia University—the same year the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution, banning the sale or transportation of all intoxicating liquors, became the law of the land. For over a decade, the forces of moral order had been busy shutting down brothels and gambling halls. Now the final piece was in place. "It is here at last!" declared the triumphant Anti-Saloon League. "Now for a new era of clean thinking and clean living!"

Maybe so in Middle America, wherever that was. But in "Gotham and Gomorrah," as that bible of the middle classes, The Saturday Evening Post, dubbed New York City, they were having none of it.

By the time Polly was marking her first anniversary in business, Manhattan had become the blazing eastern front of the first great culture war of the twentieth century. In one of the most spectacular examples of the law of unintended consequences in American history, Prohibition gave the world of vice a cachet it had never had before.

"From the parlor of my house I had a backstage, three-way view," remembered Polly with pleasure. "I could look into the underworld, the half-world and the high." Her house became a favorite oasis of the bootleggers and bookmakers who were eager to blow their ill-gotten gains. But Polly had even bigger ambitions, requiring her to master the art of publicity. She cultivated gossip columnists and influential newspapermen and she frequented the chic nightclubs and late-night rendezvous with a rotating posse of glamour girls.

By 1924, her house had become an after-hours clubhouse for the adventurous Broadway bohemians who gathered at the Algonquin Hotel for lunch; writers, performers, and publicists like Dorothy Parker, Robert Benchley, Donald Ogden Stewart, and the king of the Broadway wisecrackers, George S. Kaufman. Their imprimatur led her to the heavy hitters of Madison Avenue, Park Avenue, and Wall Street.

Executives in the garment industry and the flourishing fields of radio, motion pictures, and advertising employed her girls to woo clients. Wall Street traders passed along stock tips on their way to the bedroom. Racketeers used her parlor as an informal headquarters where they could confer with politicians and judges, away from prying eyes. Gamblers found it a safe haven for high stakes poker and crap games. Entertainers knew they'd hit the big time when they could afford an evening with her girls. Crooked cops of every rank made her place their home away from home—a decidedly mixed blessing.

There was danger in such notoriety, however. That spring she'd caught the attention of the undercover investigators of the Committee of Fourteen, a coalition of moral reformers committed to stamping out prostitution and sexual deviancy in New York. They'd tracked her to the Kentucky Club, where she was an avid fan of Duke Ellington and his sizzling jazz band. They'd traced her to the Dover Club, where comedian Jimmy Durante had hired one of her occasional call girls to work as a hostess and comic performer. If the Committee decided to stir up the wrong people, she could be in for trouble, no matter how many palms she greased.

Then there was the problem of her parents. With her newfound fortune, Polly had brought her father and two of her brothers to New York from eastern Europe. In June 1927, Moshe Adler filed his naturalization papers to become a citizen, and she planned to bring her mother and three youngest brothers to America in the coming months. Much as Polly longed to see her mother again, she dreaded the prospect of lying to her face. Her father might have understood her career—he was a man of the world—but her mother would be devastated if she learned the truth.

At this point, Polly could have declared victory and retired from the life. In an era when well-paid women made about thirty dollars a week, she was pulling in at least $60,000 a year, well over $900,000 in today's currency. She was heavily invested in the stock market and had saved a fine nest egg—enough to buy into a legitimate business or go back to school. She'd spent enough time around horseplayers and dice-tossers to know the golden rule: the only way to beat the odds was to quit the game when you are winning.

But that wasn't so simple. It was an axiom of the underworld: once in the rackets, always in the rackets. Her career was deeply intertwined with syndicated crime, and the mob didn't look kindly on retirement. As one gangland titan warned her, "Once you're tagged as a madam it's for keeps."

Besides, she wasn't sure she was ready to retire. She was only twenty-seven, but she'd seen enough of human hypocrisy to know that in the square world, she'd be just another nobody, or worse. "As Miss Pearl Adler, the reformed procuress and honest citizen, I was a social outcast," she said tartly. "As Madam Polly, the proprietress of 'New York's most opulent bordello,' society came to me."

The way her luck was running, she just needed to stick it out a little longer, until she had so much money that she'd never have to work again and no one would dare look down on her. Ask any gambler: only a rank sucker would drop the dice when she had a hot hand.

From the book "Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age" by Debby Applegate. Copyright © 2021 by Debby Applegate. Published by Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

For more info:

- "Madam: The Biography of Polly Adler, Icon of the Jazz Age" by Debby Applegate (Doubleday), available in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats via Amazon and Indiebound