Book excerpt: "A Fool's Errand" on what America needs to remember

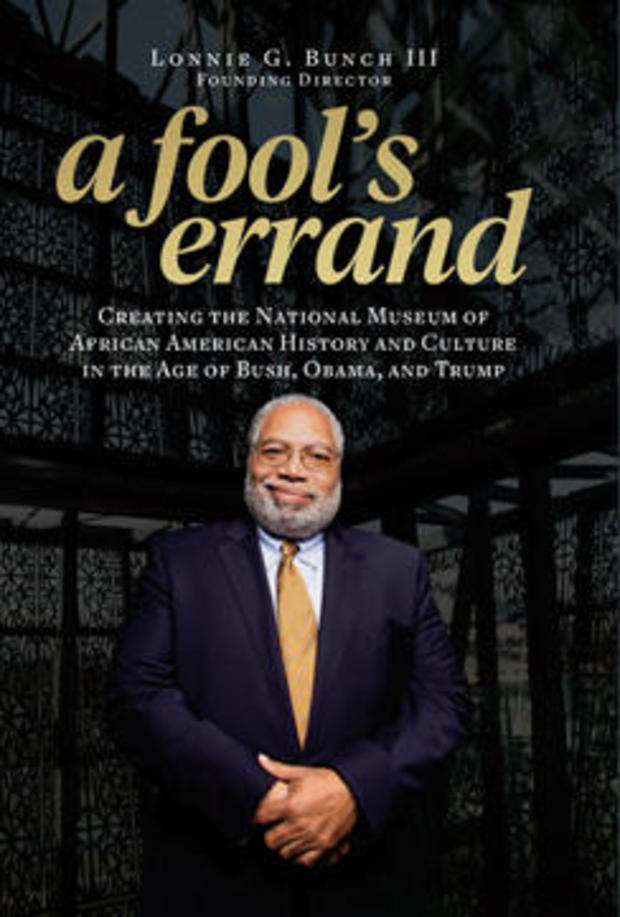

In June 2019 Lonnie G. Bunch III was named Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, which he calls "part of the glue that holds the country together." The position comes after having overseen the creation of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

In his new book, "A Fool's Errand" (Smithsonian Books), Bunch writes about a career in the pursuit of history, and the opening of the museum that was the culmination of a 14-year quest. Read an excerpt from "A Fool's Errand" below, and don't miss correspondent Chip Reid's interview with Lonnie Bunch on "CBS Sunday Morning" September 29!

Success is not final, failure is not fatal: It is the courage to continue that counts. —WINSTON CHURCHILL

My mantra for that day, September 24, 2016, was whatever you do, don't trip and fall. After eleven years of struggling, believing, convincing others to believe, threading the political needle, and surviving nearly 495 fundraising sojourns, tens of thousands had gathered on the National Mall to bear witness to the opening dedication ceremony of the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of African American History and Culture. Sitting under the museum's "porch" on a stage with President and Mrs. Obama, former President Bush and First Lady Laura Bush seated just in front of me, Chief Justice John Roberts, the Chancellor of the Smithsonian across the stage from me, the American icon John Lewis next to me, and an array of senior Smithsonian officials everywhere, I finally let myself accept the enormity of what we had accomplished and what the opening of a museum intended to help America confront its tortured racial past could mean to a nation weary of a divisive presidential campaign, and a country still struggling to define its identity in the twenty-first century. To control my nerves, I forced myself to take in the crowds, the more than 7,000 VIPs (in other words, their sup- port had earned them chairs) and the multitude who watched the ceremony on Jumbotrons from the hillside and from the grounds of the Washington Monument. I realized how much I did not want this moment to end. I did not want to forget a single second because while the success of this endeavor was due to the efforts of hundreds, the vision and the stress of leadership was mine alone.

I was gratified to see an audience more representative of America's diversity than what one commonly experiences in Washington. The crowd, while well represented by those usually associated with this company town— former President Bill Clinton, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan, Nancy Pelosi, Minority leader—also included museum supporters and visitors who just wanted to experience this moment. It felt more like a mini-Obama-like inauguration rather than the celebration of a museum opening. Even the speeches soared to match the significance of the moment. President Bush delivered what I consider to be the best speech of his career, reminding us that slavery was America's original sin and that a great nation embraces its past rather than hides from its moments of pain or evil.

I was so moved by President Obama who could not conceal his emotions as he framed the African American experience as not a separate or shameful past, but a key part of who we are as Americans. And Congressman John Lewis, standing with the moral authority of someone beaten but not broken during the Civil Rights Movement, as he sought to help a nation bind its racial wounds using the museum as part of the healing balm. What lightened my mood and lessened my fear was listening to Patti LaBelle sing the song I requested, Sam Cooke's "A Change Is Gonna Come." Her rendition reminded us that even in the most difficult time, change was possible. Her closing line that the change would be Hillary was embraced by the audience, especially Bill Clinton who leaped from his seat, would ultimately be proven wrong only a few weeks later.

As the "Voice of God" called me to speak, all I could think about was how Congressman Lewis's feet were blocking my path to the podium. After eleven years, all I could do was pray, please Lonnie, don't trip because that is all that anyone would remember. I managed to arrive at the podium, and I was choked with emotion and gripped with fear. And, once again, I was over- whelmed when I saw so many people standing, applauding, and calling out my name. At that moment, my thoughts turned to my father and grandfather, both named Lonnie. My grandfather, who began life as a sharecropper on the Perry Plantation outside of Raleigh, North Carolina, had sparked my love of history, and my Dad, a scientist and teacher whose race had limited his career options, had prepared me to be a black man in America. My mind drifted back over the years it had taken me to arrive at this setting. I could never have imagined all the experiences, disappointments, times of great joy, all the visits, and all the people I would encounter. Most importantly, I felt the spirit of my namesakes, the other Lonnie Bunchs, because in many ways the crowd was honoring them too, their struggles and their lives, as much as they were recognizing me. I could not believe that the one hundred-year-long journey— and my own eleven-year sojourn—to create a black presence on the National Mall was over.

So many experiences throughout my career had prepared me and positioned me for this, the grandest challenge of my life, what some have labeled my calling. As a young curator at the National Museum of American History, I had been tasked to lead a curatorial team to craft an exhibition that explored America during the nineteenth century. A major element of the exhibition would explore the impact and the legacy of the enslaved. To humanize the experience of slavery, I wanted to focus on a single plantation as a microcosm of the history of the peculiar institution. I traveled throughout the South in search of the perfect subject. I visited sugar plantations in Louisiana and cotton plantations in Alabama and tobacco farms in North Carolina. Eventually I was taken to the Friendfield estate, a rice plantation outside of Georgetown, South Carolina. There, standing next to a slave cabin extant since the 1840s was Princy Jenkins. In his nineties, Mr. Jenkins had once lived in one of the cabins with his enslaved grandmother.

To tap the knowledge Princy Jenkins had about the life of the enslaved on that plantation was the Holy Grail for a young historian. He told me how the enslaved did a "hard sweep" in the front of the cabin to kill the grass so there would be no vermin near their home. He took me to the rear of the cabin and explained the food that the enslaved grew to supplement the rations they were given. Next we went to one side of the cabin and he spoke about the role children played in monitoring the chimney to alert the adults in case of fires. Then I went to the other side of the cabin, but Mr. Jenkins would not accompany me. I asked him what had happened there and he again refused to come to that side of the cabin. Finally, I implored him to explain, and he just said that he would not come over because there was nothing but rattlesnakes living there. After I stopped running, I asked him why he had not mentioned how dangerous that spot might have been. He replied that people used to remember, now too much is forgotten. He then said words that have shaped my career: if you are a historian then your job better be to help people remember not just what they want to remember, but what they need to remember. Right after he said those words, he shook my hand and left me standing alone by the cabin as he returned to his work as the caretaker of the plantation. I never saw him again and I am sorry that I did not have the foresight to thank him for sharing his wisdom and his history with a stranger from Washington, DC.

The struggle to help reshape America's memory, to recenter race in the construction of the nation's identity, and in the words of Mr. Jenkins to remember what America needed to remember, not just what it wanted to recall about the role and impact of African Americans, by creating a place on the National Mall was a century-long battle. From 1915, the idea for a memorial in Washington was initiated by African American veterans of the Civil War whose presence and contributions to the Union victory had not been included in many of the commemorations that accompanied the fiftieth anniversary of the war's conclusion. At a time when racial segregation was the law of the land, when hundreds of African Americans were lynched and brutalized annually, when the images of blacks in film, in advertising, and in the media were ripe with stereotypes that denigrated and dehumanized, the idea to create a counternarrative was embraced by many in the African American community. It was hoped that this entity would not only honor the patriotism of the African American soldier but would also have a physical space for programs and presentations that would expand America's knowledge about the black community. Just at this initiative was getting organized the First World War seized the nation's attention and the monument was never constructed.

During the 1920s, a diverse array of African Americans, including Mary McLeod Bethune, W.E.B Du Bois, Mary Church Terrell, and Kelly Miller, supported the notion of a black presence on the National Mall. A campaign made visible, in part, by the African America press led to the hiring of Harlem architect Eric R. Williams, who created the preliminary design for what was called the National Negro Monument. In 1929, the US Congress would pass Public Law 107, signed by President Calvin Coolidge, that would support the creation of such a building, but it would need massive nonfederal fundraising support, something that the onset of the Great Depression made impossible.

The notion of recognizing the contributions of black Americans gained currency as the nation struggled to change during the post-World War II Civil Rights movement. To many, among them Congressman James Scheuer, a Democrat from New York, the Civil Rights struggle should also broaden American education to include the presence and contributions of blacks. In 1966, Congress created a commission to study the feasibility of a National Negro History Museum. Though there were concerns raised by the fledgling African American museums and art galleries in numerous urban centers that a national presence may hurt their efforts, many leading African American figures testified in support of this museum—baseball legend Jackie Robinson, Betty Shabazz, widow of Malcolm X, the author James Baldwin, to name only a few. Just as the commission moved forward, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in 1968, and the nation's gaze turned away from the creation of a cultural institution.

The idea for a national presence lay fallow until the mid-1980s when an African American businessman who created the most successful tour mobile company in the nation's capital, Tom Mack, contacted Congressman Mickey Leland to campaign for a national museum on the Mall. Soon joined by Civil Rights hero, John Lewis, Leland began to push for legislation that would create a stand-alone black museum. Time and time again, the bills failed to work their way through the legislative process. In the early 1990s, a bill passed the House of Representatives, but was squashed in 1993 when Senator Jesse Helms prevented it from receiving a vote in the Senate. After Leland's death in 1989, Congressman Lewis, working with a group of Congressional colleagues, introduced legislation that seemed destined to failure every year.

The Smithsonian was always ambivalent about the creation of a national museum that explored the black experience. As early as 1989, the leadership of the Smithsonian in the presence of Secretary Robert McCormick Adams opposed a separate museum and instead proposed that "just a wing" of the National Museum of American History be dedicated to this history. This remark generated a great deal of negative criticism and led the Smithsonian to bring one of the leading African American museum professionals in the nation, Claudine Brown, to assess the Smithsonian's efforts at interpreting and preserving black culture by conducting a study of the issues involved with creating a museum. Brown brilliantly evaluated the need for this work and explored the challenges to this task, including the limited number of professional people of color at the Institution. After a careful and detailed analysis, Brown encouraged the Smithsonian to create a national museum. Though new leadership arrived at the Smithsonian in 1994 with the appointment of I. Michael Heyman as the tenth Secretary, the Institution still questioned the need for "ethnic" museums on the Mall, but as a concession to the growing interest in a museum in Congress, Brown received the institutional support to create the Center for African American History and Culture, not as a stand-alone museum but as a unit housed within the aging Arts and Industries Building. This would allow Ms. Brown and her colleagues to enhance and enrich the African American presence on the Mall in ways that the National Museum of American History did not have the staff or the space to accomplish.

In 2001, legislation introduced by John Lewis and Representative J. C. Watts Jr. to create a twenty-three-member Presidential Commission to evaluate issues of location, cost, and collections was enacted and signed by President George W. Bush. Led by Dimensions International CEO Robert Wright and Claudine Brown, the commission released its report strongly advocating for a national museum on April 3, 2003. Six months later in November 2003, legislation crafted by John Lewis, J.C. Watts, Senator Sam Brownback, and Senator Max Cleland, the "National Museum of African American History and Culture Act" (Public Law 108–184) was enacted. Nearly ninety years after the idea was first broached, legislatively, the museum existed. As my father used to say, "patience is a virtue." But ninety years was a long time to be virtuous.

During the years leading to the passage of the museum legislation, I was blissfully distant. In January 2001, after thirteen years as a curator and later as the Associate Director for Curatorial Affairs at the National Museum of American History, I left Washington to become the President of the Chicago Historical Society (CHS, now the Chicago History Museum), one of the nation's oldest museums that was venerated but not visited. Leaving the Smithsonian was extremely hard and I had to come to grips with the fact that I would probably never return to the place where my career had begun and flourished. So as I settled into my first job as a museum director I never thought about the National Museum of African American History and Culture—much.

Once the legislation was passed and the Smithsonian was in search of institutional leadership, I was startled by the number of board members of the CHS and university and museum colleagues and friends at the Smithsonian who assumed that the job of founding director was mine or, at least, that I would want to be considered for the position. And during my time at the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), I came to realize this job was my calling, but in late 2004 when I was first approached about the possibility I was less than interested. In fact, I turned down the chance to compete several times. There were many factors for my reluctance. The sheer enormity of the task was such a daunting challenge. The charge of conceptualizing and building a national museum, one potentially on the National Mall, was frightening enough, but even more unsettling was the reality that this was a museum of no: no staff, no site, no architect, no building, no collections, and no money. And it carried the weight and the burden of history. It was both the pressure of fulfilling dreams that had been deferred for nearly a century and the realization that this museum would became the national arbiter and legitimizer of African American culture and history in ways that would overshadow all the years of amazing scholarship emanating from the nation's universities and colleges. I was not John Hope Franklin, Benjamin Quarles, Letitia Brown, Marion Thompson Wright, Sterling Stuckey, or any of the other pioneering scholars whose work and creativity forced the academic canons to make way for African American history and culture. I did not know if I could create a museum that was worthy of their efforts and talents.

I was also not sure that I was willing to make the personal and professional sacrifices needed to make real the hopes of so many generations. And I was uncertain whether I wanted to spend a decade or more of what could be considered the prime of my career to take on a project that even the most ardent supporters doubted would be realized in their lifetimes. When Hill Hammock, chair of the board of trustees at the CHS, learned that my name was being bandied about, he suggested that it would be better to be the second director of the museum because the burden of being the founding leader would be too great.

There was no denying that the pressure, the visibility, and the risks would be huge. I wrestled with the impact of taking this job would have on my family and my health. If I did return to Washington, it meant that I would have to commute for at least a year. When I left Washington to head the Chicago Historical Society, my oldest daughter was entering her last year in high school and my family had to stay in the area so she could graduate with her class. The family remained and I commuted each week. I hated the commute. The 6 a.m. Monday morning flights. The rush to attend early morning meetings. And the loneliness of coming home to an empty apartment with the only activity of the evening being the choice of which microwavable dinner to blast. I did not fancy having to repeat that experience since my youngest daughter would complete her senior year in high school while I commuted to the Smithsonian. And though I have been labeled a "public historian," the reality is that I am quite private. I wondered if I wanted or could handle the media scrutiny that would accompany being the face of a museum that did not yet exist. Though at that point I had no idea just how much attention I would attract.

The most important factor in my hesitation was the symbolism of an African American as president of a major cultural institution in a city like Chicago. Throughout my career I have always been critical of a museum profession that was awash in whiteness. The lack of diversity, especially in leadership positions, means that museums have not made the commitment to their communities or to their colleagues to be institutions that grapple with our differences. To see culture, history, and the arts as more than sources of beauty, exoticism, and nostalgia, but to use them as tools that help the audiences navigate the challenges of contemporary America. In an article I wrote twenty years ago, "Flies in the Buttermilk: Museums, Diversity, and the Will to Change," I challenged the museum profession to train, promote, and hire people of color as leaders of institutions. In Chicago I had the chance to demonstrate how diverse leadership can make an organization better. Our nearly five years of success included increased visitations and visibility, and exhibitions and programs that mattered. And our institution was being seen as a museum valued by an array of communities. I hoped that I had opened doors at other institutions to appreciate and nurture people of color. In essence, my fervent hope was that my work in Chicago would provide greater access to positions of influence and ensure that future generations of diverse scholars and museum professionals would not have to refight the battles I had fought. I worried that taking the helm of what some people felt was another "black museum" would be taking a step back, that I would be retreating from the struggle that had shaped my whole career.

Ultimately, the possibilities and the challenges of creating a national museum proved too alluring to resist. Being president of the Chicago Historical Society nurtured my soul. Yet being part of the birth of the National Museum of African American History and Culture nurtured the souls of my ancestors. Until I returned to the Smithsonian in 2005, I had never written about or mentioned ancestors. But the museum should be about more than an individual's dream. This endeavor was more important than anything I could ever do. To me success was doing work that would make my ancestors smile. And the opportunity to make them smile was part of what convinced me to pursue this position. I was, however, also moved by the potential to put in place ideas, values, and stories that mattered to me, that were often overlooked. The museum would not be about me, but it would be a laboratory to test and to implement my hopes for what a museum could be in the twenty-first century. I wanted a museum that was a tool to help people find a useful and usable history that would enable them to become better citizens; a museum that would explore and wrestle with issues of today and tomorrow as well as yesterday. I craved to be part of an institution that was of value both in the traditional ways of curating exhibitions, enriching education opportunities, and preserving collections and in nontraditional ways, such as being a safe space where issues of social justice, fairness, and racial reconciliation are central to the soul of the museum.

Excerpt from "A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump" by Lonnie G. Bunch III. Copyright 2019 by Lonnie G. Bunch III and Smithsonian Institution. Republished by permission. All rights reserved.

For more info:

- "A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump" by Lonnie G. Bunch III (Smithsonian Books), in Hardcover and eBook formats, available via Amazon

- Book tour info – New York City (Oct. 1); Philadelphia (Oct. 15); Cambridge, Mass. (Oct. 23); New Haven, Conn. (Oct. 24); and Los Angeles (Nov. 16)

- Smithsonian Institution