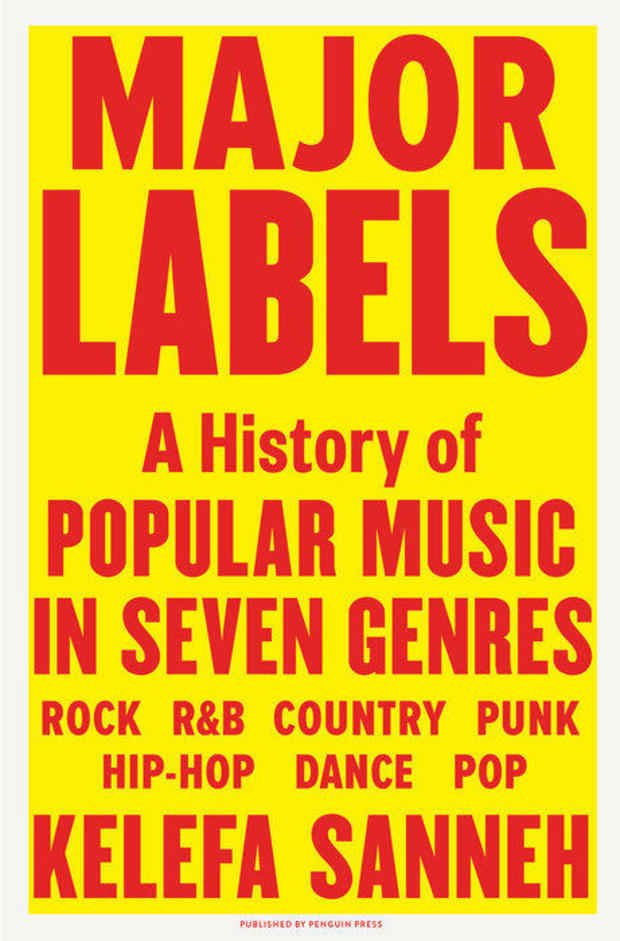

Book excerpt: Kelefa Sanneh's "Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres"

In his new book, "Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres" (Penguin), New Yorker writer and "Sunday Morning" contributor Kelefa Sanneh examines the genres that have dominated popular music over the last half-century.

You can read an excerpt below, and also listen to Kelefa Sanneh narrate his introduction of "Major Labels," from the audio book release. You can also watch Sanneh's report on "CBS Sunday Morning" October 3!

To listen to an excerpt from the audiobook of "Major Labels" click on the embed below:

Literally Generic

I am always a bit puzzled when a musician is praised for transcending genre. What's so great about that? In visual art, "genre painting" refers to works that depict normal people doing normal things. In publishing, "genre fiction" is the down-market counterpart of literary fiction. And moviegoers talk about "genre films," a term applied to films that fulfill the basic obligations of a certain genre, like horror movies or heist movies—and, it is often implied, do no more than that. But in popular music, genres are all but inescapable. In the old days of record stores, every record in the store had to be filed somewhere. And even streaming services find it useful to rely on these categories; if you want to explore Spotify, the first option you are offered is to browse by "Genres & Moods." The idea of transcending genre suggests an inverse correlation between excellence and belonging, as if the greatest musicians were somehow less important to their musical communities, rather than more. (Did Marvin Gaye transcend R&B? Did Beyoncé?) Sometimes musicians are praised for mixing genres, although I'm not convinced that mixture is necessarily better than purity, or a more reliable route to transcendence. It is strange, anyway, to praise genre mixing without also praising the continued existence of the genres that make such mixing possible.

Musicians, I have learned, generally hate talking about genres. And reasonably enough: it's not their job. Virtually every music interview I have conducted has elicited some version of the sentence "I don't know why it can't just be 'good music.'" No doubt this sentiment captures something true about many musicians, especially accomplished ones. They hate being labeled. And they think more about the rules they break than about the ones they follow, reveling in a sense of freedom—especially in the recording studio. (I wouldn't know firsthand: although I eventually moved from playing violin in my high school orchestra to playing guitar and bass in bands, I never achieved anything beyond rudimentary competence, and that only sometimes.) But typically, musicians have a sense of who their peers are, even if they insist that comparisons are worthless. Typically, too, they have a sense of industry and audience expectations, even if they say they love to confound them. Often their comments, like their albums, reflect a series of assumptions that they're scarcely even aware of: about what qualities might make a track acceptable to radio programmers; about what sorts of collaborations might be considered valuable, or surprising; about how songs are made and when they are finished. Country singers, for instance, have sometimes bucked country tradition by recording their albums with members of their touring bands instead of Nashville session musicians. But most noncountry singers probably didn't even know this tradition existed. You can't really rebel against a genre unless you feel part of it, too.

In many conversations and books about music, genre obsessives are the enemy. They are the mercenary record executives, intent on fitting each new act into a neat little box, just to make life easier for the marketing department. And they—we!—are the myopic music critics, too busy categorizing music to truly listen to it. Still, this book is a defense of musical genres, which are nothing more or less than names we give to communities of musicians and listeners. Sometimes these have been physical communities, revolving around record stores or nightclubs. More often, they have been virtual communities, sharing ideas and opinions through records and magazines and mixtapes and radio waves; especially in the era before social media and before the Internet, fans sometimes had to take it on faith that there were other people out there listening, too. I think the story of popular music, especially over the past fifty years, is a story of genres. They strengthen and proliferate; they change and refuse to change; they endure even when it looks as if they are dying out or blending together. (It seems that every decade or so, a genre becomes so popular that people worry it is disappearing into the pop mainstream.) The persistence of genres—the persistence of labels—has shaped the way music is made and also the way we hear it. And so, this book aims to acknowledge that. This book is literally generic.

It can be slightly deflating to view popular music this way, and I don't think that's a bad thing. Pop music, broadly defined, has a tendency toward irreverence, and yet it is often discussed in worshipful tones, as the product of a succession of charismatic geniuses. And indeed, many of those familiar geniuses play a role in these histories, from Johnny Cash to the members of N.W.A. But if you emphasize genres, you inevitably find yourself thinking about the other stars, too—the hitmakers who don't tend to get celebrated in blockbuster movies. Like Grand Funk Railroad, for a time one of the most popular rock bands in America, even if many critics couldn't figure out why. Or Millie Jackson, an R&B trailblazer who couldn't quite reconcile herself to disco. Or Toby Keith, who epitomized so much about what people loved, and hated, about country music in the 2000s. Many of the musicians in this book didn't transcend their genres, sometimes because they didn't care to try, and sometimes because they tried and failed. Some of them battled the perception that their music was "generic" in a pejorative sense—as if any musical act embraced by a particular community must therefore be unimaginative. But this criticism of "generic" music is merely a restatement of the most common criticism of popular music in general: that there is something corrupting about certain kinds of popularity. Over the past half century, many musicians and listeners have belonged to tribes. What's wrong with that?

From "Major Labels" by Kelefa Sanneh. Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Kelefa Sanneh, 2021.

For more info:

- "Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres" by Kelefa Sanneh (Penguin), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available October 5 via Amazon and Indiebound

- Kelefa Sanneh at The New Yorker