Boeing failing to keep track of non-conforming parts, whistleblower says: "It's like Russian roulette"

When a panel known as a door plug blew off an Alaska Airlines flight minutes after takeoff earlier this year, a quality investigator at the factory where the Boeing plane was manufactured says he wasn't surprised; he said he was almost expecting something like this would happen.

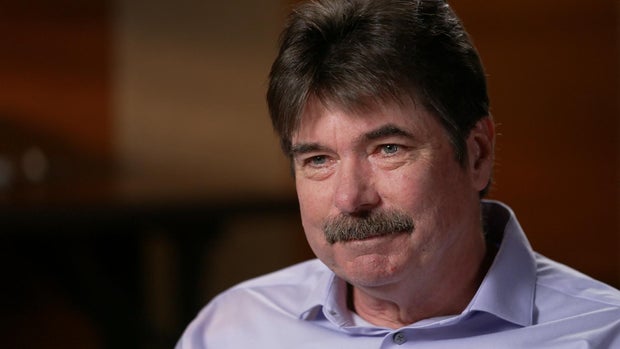

Whistleblower Sam Mohawk is speaking publicly for the first time about the problems he's seen during his 13 years working in quality assurance at Boeing's commercial airplane factories. Months before the door plug incident, Mohawk said he warned both Boeing and federal regulators about lapses in safety practices inside the company's Renton, Washington factory, which is responsible for building about 30% of the world's commercial jet fleet. Mohawk believes defective or "non-conforming" parts are not being properly tracked there and could be making it onto Boeing planes – a concern he said could lead to a catastrophic event without a proper investigation.

"It might not happen within the first year, but down the road they're not going to last the lifetime that they're expected to last," he said. "It's like Russian roulette, you know? You don't know if it's going to go down or not."

"A desperation for parts" at Boeing's Renton factory

A month after the Alaska Airlines incident, the National Transportation Safety Board investigation concluded the four bolts required to secure the door plug that blew off the Boeing 737-9 Max were removed during production at that Renton facility and never reinstalled. After an extensive search, NTSB investigators determined the records to document the removal of those four bolts don't exist. Boeing said it can't find any paperwork to explain how a plane left its factory without the bolts.

Mohawk said he started noticing problems at the Renton facility during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Boeing was ramping up production and dealing with supply chain issues.

"The idea is to keep those airplanes moving, keep that line moving at all costs," he said.

As a quality investigator, part of Mohawk's job is to keep track of defective airplane parts in what some employees call "the parts jail." It's called that, Mohawk said, because the parts are meant to be under lock and key and tracked like a chain of evidence. But Mohawk says that amid pressure to keep production moving, some employees sidestepped Boeing protocol and took bad parts out of the "parts jail" when his team wasn't looking.

Mohawk's concern is that those bad or "non-conforming" parts he says are getting lost or taken, could be ending up on planes.

"There's so much chaos in that factory," Mohawk said. "There's a desperation for parts. Because we have problems with our parts suppliers. So there's, in order to get that plane built and out the door in time, I think unfortunately some of those parts were recycled back onto the airplanes in order to build, keep building the airplane and not stop it in production."

Mohawk believes it's happening repeatedly.

"We have thousands of missing parts," he said.

It's not just parts like bolts that are going missing, according to Mowhawk, but also rudders, one of the primary tools for steering planes. Mohawk said 42 flawed or "non-conforming" rudders, which he says would likely not last the 30-year lifespan of a jet, have disappeared..

"They're huge parts," he said "And they just completely went missing."

NTSB safety reports show the number of Boeing plane accidents has declined over the last two decades, but Mohawk is still concerned.

"Right now, the Max is a new program," he said. "So these airplanes that are having the quality issues are brand new to the fleet. We don't know what's going to be coming in the future."

The Max line, certified by the FAA in 2017, has drawn scrutiny since its first year in service.

Workers at the Renton factory, where they make the Max, returned to work last month after a seven-week strike, After their return, there was a focus on training and making sure the factory had "the supply chain sorted out." Production has now resumed at Renton.

Mohawk still works there. In June, he filed a federal whistleblower claim to protect himself from potential retaliation. Mohawk also reported his concerns to the FAA, which is investigating his claims, and hundreds of others directed at the company.

"I put a big target on my back in there," he said.

Despite that, he felt it was important to come forward.

"At the end of the day my friends and family fly on these airplanes," he said.

Stories out of Renton echo those in Charleston

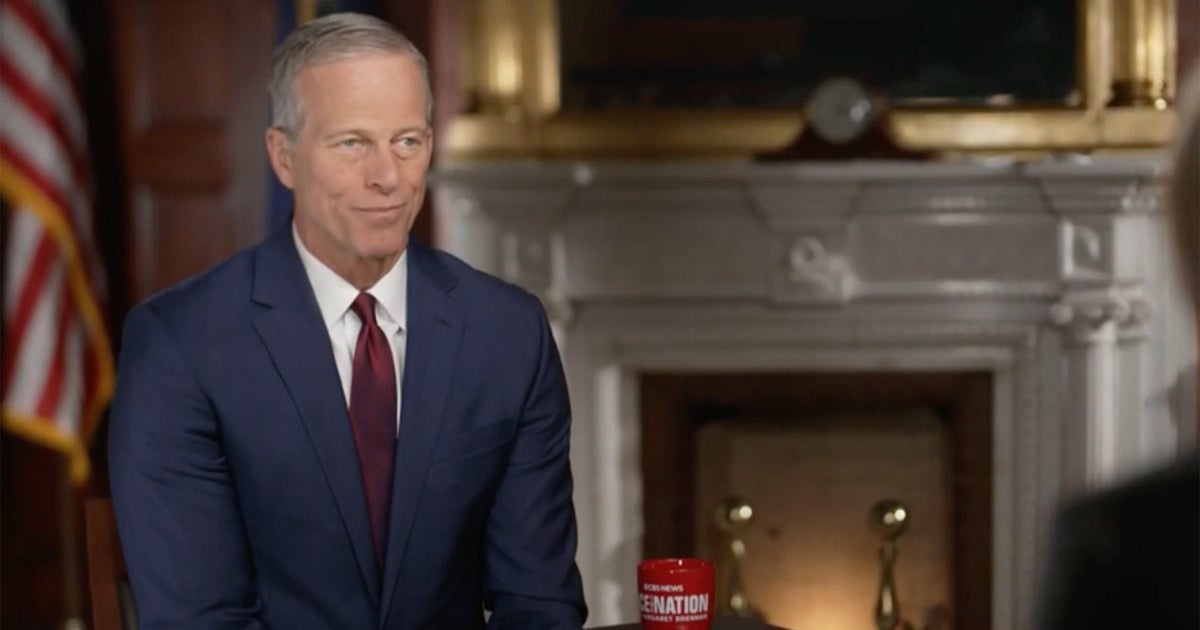

According to the Federal Aviation Administration, whistleblowers at Boeing submitted more than 200 reports over the last year. Their safety concerns include mismanagement of parts, poor manufacturing and sloppy inspections at Boeing.

Mohawk's story echoes another Boeing whistleblower at another Boeing plant, John Barnett. He spent three decades at Boeing and began working as a quality manager on the long-haul 787 Dreamliner at the company's South Carolina factory in 2010.

Barnett said managers there pressured workers to ignore FAA regulations, such as not tracking defective parts properly. He said Boeing then retaliated against him for speaking up. Boeing has denied his claims.

In 2017, Barnett retired and contacted Charleston attorney Rob Turkewitz, who's worked with dozens of Boeing employees over the last decade. Turkewitz said Barnett had more than 3,000 internal documents — emails and photos from Boeing — to support his whistleblower claims.

Seven years later, Barnett was in the final stretch of his case.

"I think that John Barnett was probably the best witness I have ever seen testify," Turkewitz said. "He knew the facts up and down."

Barnett was scheduled to complete his final day of depositions on March 9. He never showed.

Turkewitz went to Barnett's hotel to search for him and learned the 62-year-old whistleblower had been found dead inside his truck. Police said it was a suicide.

Turkewitz called Barnett's family, including his mom, Vicky Stokes, and his brothers, Rodney Barnett, Robby Barnett and Michael Barnett.

"He put up a good front with us, but you, you know, times when we really had heart-to-heart conversations, you could tell it just wore on him," Michael Barnett said. "You know, I'd ask him, 'Why do you want to — why do you just keep pursuing it?" And he's just, like, 'Because it's the right thing to do. Who else is going to do it?'"

The Barnett family is continuing his legal fight.

More Boeing workers speak up

Barnett's death also inspired other Boeing workers to speak up. Merle Meyers, who'd worked with Barnett, said he was angry when he learned how Barnett was allegedly treated.

Meyers started his 30-year career at Boeing as a parts inspector. He worked as a quality manager at the company's largest plant, located in Everett, Washington, before he left last year. Meyers' concerns first began in 2015, when he said he discovered defective 787 landing gear axles that had been scrapped, back at the factory.

"They were corroded beyond repair," Meyers said.

Meyers said workers, driven by schedule pressure, took the axles to avoid stalling production.

Photos provided to 60 Minutes show the axles spray-painted red and clearly marked as "scrap." Meyers said he learned scrap parts marked like this had been taken without authorization for over a decade. Sometimes people used chemical cleaners to remove the paint, Meyers said.

Boeing says it thoroughly investigated Meyers' claims and that the defective axles did not make it onto airplanes. But Meyers says the competition for airplane parts continued.

"They would talk openly about it at the stand-up meetings, senior managers," Meyers said.

They'd compete for parts, both good and bad, he said.

"They're not too picky," he said.

Meyers alleges company vice presidents were at those meetings and would do nothing about what they heard.

"Speak up until my face is blue"

Boeing employee Sam Salehpour worked in aerospace as an engineer for 40 years. Earlier in his career he worked on rockets, including for companies supporting the Challenger Space Shuttle, which exploded in 1986, killing seven people, though Salehpour didn't work on the Challenger.

"Ever since that explosion I have promised myself, 'If I see problems that they are concerning, or safety-related, I am going to speak up until my face is blue,'" Salehoupour said.

He now works on the 777 line in the Everett factory, where Meyers worked. Salehpour says when the jet is assembled, pre-drilled holes are supposed to line up to join pieces together. Salehpour told federal investigators that when they didn't, he witnessed Boeing employees trying to force them to line up.

"They were jumping up and down like this," Salehpour said. "When I see people are jumping up and down like that to align the hole, I'm saying, 'We have a problem.'"

Salehpour described how he believes that kind of pressure on parts could impact the lifespan of a plane.

"That's like going one more time on your paperclip, OK? And we know that paper clip doesn't break the first time, the second time, the third time," Salehoupour said. "But it may be breaking on the 30th or the 40th time."

Salehoupour alleges this is still happening at Boeing.

Boeing responds to whistleblowers

In a statement to 60 Minutes, Boeing said it carefully investigates all quality and safety concerns, including those of the whistleblowers 60 Minutes spoke with. Boeing said:

"Every day, thousands of Boeing airplanes take off and land around the world, and we are dedicated to the safety of all passengers and crew on board. Our employees are empowered and encouraged to report any concern with safety and quality. We carefully investigate every concern and take action to address any validated issue.

The current and former Boeing employees interviewed by 60 Minutes previously shared their concerns with the company. We listened and carefully evaluated their claims, and we do not doubt their sincerity. Some of their feedback contributed to improvements in our factory processes, and other issues they raised were not accurate. But to be clear: Based on investigations over several years, none of their claims were found to affect airplane safety.

Commercial air travel is the safest form of transportation – and our industry continues improving its exceptional safety record – in part because people do speak up about potential issues. We encourage and welcome employees' feedback and will continue to incorporate their ideas to make Boeing better."