Boeing whistleblower says "thousands" of faulty or nonconforming parts go missing during plane production

Most of you watching tonight have probably flown on an airplane made by the Boeing Company. That's why you may have been more than a little rattled when a panel blew off the side of one of its airplanes in January, leaving a gaping hole and a lot of questions for the renowned American company.

Since then, four federal investigations have been launched and Boeing hired a new CEO to quote "restore trust."

But that hasn't stopped a steady stream of Boeing whistleblowers from coming forward. The FAA says over the last year, it's received more than 200 reports from whistleblowers. Their safety concerns include mismanagement of parts, poor manufacturing and sloppy inspections at Boeing.

You're about to hear from some of those whistleblowers. They told us why they weren't surprised when a Boeing airplane blew open in the Oregon sky.

This was the view from the cabin thousands of feet above Portland. for 14 terrifying minutes…nothing stood between the 177 people on the Alaska Airlines flight and the cold evening sky.

The distress call came shortly after take off when a panel over an exit that's only opened for maintenance…called a door plug...blew off three miles above the ground.

The plane…a Boeing 737-9 Max, just a few months old, landed safely and remarkably, no one was seriously injured.

A month later, the National Transportation Safety Board's investigation revealed four bolts required to secure the "Max's" door plug were removed during production at Boeing's factory in Renton, Washington and never reinstalled.

Boeing says it can't find any paperwork to explain how a plane left the factory broken.

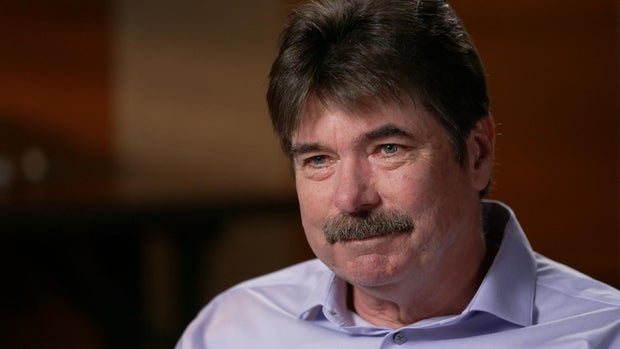

Sam Mohawk works at that Renton factory. This is his first television interview.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So in January when you heard about the lost door plug incident? What was your reaction?

Sam Mohawk: Um I was not surprised. I was almost expecting something to happen. I was actually happy that it wasn't a cata--catastrophic event that took down an airplane. That kind of put visibility, what was going on internally out to the public.

Mohawk has worked for Boeing for 13 years on three different airplane programs. Months before the door plug incident, Mohawk says he warned Boeing and federal regulators about lapses in safety practices inside the Renton factory, which makes about 30% of the world's commercial jet fleet.

Sam Mohawk: The idea is to keep those airplanes moving, keep that line moving at all costs.

Sharyn Alfonsi: At all costs?

Sam Mohawk: At all costs.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Even safety?

Sam Mohawk: Unfortunately, yes. Yeah.

Mohawk says he started noticing problems during COVID when Boeing was ramping up production and dealing with supply chain issues.

Part of his job as a quality investigator is keeping track of defective airplane parts in what employees call quote "the parts jail."

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why parts jail?

Sam Mohawk: Because they're supposed to be under lock and key. And it's supposed to be, like, a chain of evidence. We're we're following that whole part to make sure that that is not a bad part going to the back to the airplane.

But Mohawk says in an effort to keep production moving, some Boeing employees sidestepped protocol and took bad parts out of "the parts jail" when his team wasn't looking.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Where do you think the parts are going?

Sam Mohawk: There's so much chaos in that factory that um there's a desperation for parts. Because we have problems with our parts suppliers. So, there's, in order to get the plane built and out the door in time, I think unfortunately some of those parts were recycled back onto the airplanes in-- in order to build keep building the airplane and not stop it in production.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You think that the faulty parts could be on Boeing airplanes?

Sam Mohawk: Yes, I do. yeah.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Are you talking about a couple bad parts being put on a plane, or is this happening repeatedly?

Sam Mohawk: I think it's happening repeatedly. We have thousands of missing parts.

And it's not just bolts but rudders, one of the primary tools for steering an airplane. Mohawk says 42 flawed or "non-conforming" rudders – that he says would likely not last the 30 year lifespan of a jet – went missing.

Sam Mohawk: Those parts came into the-- our system. They're huge parts. And they just completely went missing. Somebody, not through our group, moved all those parts away.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If they're using non-conforming parts and they're putting them on airplanes, what's the concern?

Sam Mohawk: I think without a proper investigation it could-- it could lead to a catastrophic event. It might not happen within the first year, but down the road they're not gonna last the lifetime that they're expected to last. It's like Russian roulette, you know? You don't know if it's gonna go down or not.

Sam Mohawk's story echoes another Boeing whistleblower, at another Boeing plant, John Barnett. He appeared on NBC's "Today Show" in 2019.

John Barnett spent three decades at Boeing. In 2010, he began working as a quality manager on the long haul 787 Dreamliner at the company's South Carolina factory.

Barnett said managers there pressured workers to ignore FAA regulations such as not tracking defective parts properly, then retaliated against him for speaking up. Claims Boeing denies.

In 2017, he retired and reached out to Rob Turkewitz, a Charleston attorney who's worked with dozens of Boeing employees over the last decade.

Rob Turkewitz: John Barnett walked into my office and told me about what was goin' on. And I asked him, I said, "Do you have documents? And he said, "Actually I do." He said, "I've got thousands of documents."

Turkewitz says Barnett had more than 3,000 internal documents, emails and photos from Boeing to support his whistleblower claim. Seven years later, John Barnett was in the final stretch of his case.

Rob Turkewitz: I think that John Barnett was probably the best witness I have ever seen testify. He knew the facts up and down. And the defense lawyer objected and said, "He's-- he's not even looking at the documents." And if I remember right, John said, "I don't need to. I live this."

Sharyn Alfonsi: He knew every detail of his case.

Rob Turkewitz: Absolutely.

John Barnett was scheduled to complete his final day of depositions on March 9 of this year.

Rob Turkewitz: And I tried calling John to see if he needed a ride and, you know, let him know I could pick him up at the hotel. And I got no answer. And when I got to the deposition at about 10 o'clock, he didn't show up.

He drove to John Barnett's hotel and learned the 62-year-old was dead inside his truck with what police said was a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Turkewitz called John Barnett's family, brothers Rodney, Robby, Michael and mom, Vicki.

Vicki: He was used to people caring and listening, and if somethin' was wrong, they fixed it. And when he started in Charleston, that wasn't the case. And he would try to go to his boss, who would not listen. And I guess that's when he felt under siege, you know. He would be embarrassed at meetings.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What did the fight do to him?

Michael: He put up a good front with us, but you, you know, times when we really had heart-to-heart conversations, you could tell it just wore on him. You know, I'd ask him, "Why do you want to-- why do you just keep pursuing it?" And he's just, like, "Cause it's the right thing to do. Who else is gonna do it?"

The Barnett family is continuing John's legal fight. His death inspired other Boeing workers to speak up.

One of them is Merle Meyers. He worked with John Barnett years ago.

Merle Meyers: When the stories came out about how he was treated by managers, some of whom I knew, I was really angry. And um he was just a really, uh, solid airplane man.

Meyers began his 30-year career at Boeing as a parts inspector. He was working as a quality manager at the company's largest plant in Everett, Washington before he left last year.

He says his concerns first began in 2015, after he discovered defective 787 landing gear axles that had been scrapped were taken by workers and brought back to the factory.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Why were they just taking things?

Merle Meyers: Schedule driven. So that's-- that's really, um, that's the order of the day.

Sharyn Alfonsi: They needed a part, they didn't wanna wait for it?

Merle Meyers: Right. Right.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What condition were these landing gear axles in?

Merle Meyers: They were corroded beyond, uh, repair.

In these photos provided to 60 Minutes, the axles are spray painted red. Meyers says he learned scrap parts marked like this had been taken without authorization for over a decade.

Sharyn Alfonsi: If the faulty parts are spray-painted red, would you be able to look at a part on a plane and go, "that's faulty?" Are they still red when they get on the plane?

Merle Meyers: Yeah, or it, it would get cleaned up.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do they clean it up?

Merle Meyers: Well, just cleaner. You know, chemicals. Chemical cleaners.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Like wash it off?

Merle Meyers: Uh-huh (affirm). Yeah.

Boeing says it thoroughly investigated Meyers' claims and that the defective axles did not make it onto airplanes. But Meyers says the competition for airplane parts continued.

Merle Meyers: And they would talk openly about it at the stand-up meetings, senior managers-- that-- that flap on that plane ahead of mine is supposed to be on mine, and that was taken by a competing manager. So managers compete.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So they're fighting for faulty parts?

Merle Meyers: Yeah. And good parts. They're not too picky.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Wow.

Merle Meyers: Yeah.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And they talked about that openly?

Merle Meyers: Uh-huh (affirm). Yeah. And vice presidents would attend that meeting often, and they would hear this and do nothing about it.

Sam Salehpour might have more reason than anyone to do something about it. He's worked in aerospace as an engineer for 40 years.

Sam Salehpour: I come from a Space Shuttle background. I don't know if you'd remember the Challenger explosion, where we lost seven people. Ever since that explosion I have promised myself, "If I see problems that they are concerning, or safety-related, I am gonna speak up until my face is blue."

Salehpour works on the 777 line in Everett. He says when the jet is assembled, pre-drilled holes are supposed to line up to join pieces together. When they didn't, Salehpour told federal investigators he observed Boeing employees trying to make them line up.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What were people doing to get the holes to align?

Sam Salehpour: Force. Crane forces, people jumpin' up and down to align the holes.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Jumping up and down?

Sam Salehpour: Yeah. They were jumping up and down like this. When I see people are jumpin' up and down like that to align the hole, I'm sayin', "We have a problem."

Sharyn Alfonsi: What happens then if you've got that pressure on these parts?

Sam Salehpour: That's like going one time more on your paperclip, okay? And we know that paper clip doesn't break the first time, the second time, the third time. But it may be breaking' on you the 30th or the 40th time.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You're saying this is-- was happening over and over again?

Sam Salehpour: It's still happenin' right now. Even right now it's still happening.

In a statement to 60 Minutes, Boeing said it carefully investigates all quality and safety concerns, including those of the whistleblowers we spoke to, telling us:

"Some of their feedback contributed to improvements…and other issues they raised were not accurate. Based on investigations over several years, none of their claims were found to affect airplane safety."

Sharyn Alfonsi: NTSB safety reports show Boeing plane accident numbers have declined over two decades, that they're safer than they've ever been.

Sam Mohawk: Yeah.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do you view that?

Sam Mohawk: Right now the MAX is a new program. So these airplanes that are having the quality issues are brand new to the fleet. We don't know what's gonna be coming in the future.

Workers at the Renton factory...where they make the Max..... returned to work last month after a 7-week strike... but the FAA says- they have not resumed production and are focused on training and quote "making sure they have the supply chain sorted out." Sam Mohawk still works there.

In June, he filed a federal whistleblower claim to protect him from possible retaliation.

Sam Mohawk: I put a big target on my back in there.

Sharyn Alfonsi: So why'd you do it?

Sam Mohawk: 'Cause I'm concerned with safety. Like, at the end of the day my fam-- my friends and family fly on these airplanes.

The FAA is still investigating Sam Mohawk's claims along with hundreds of others related to the Boeing company.

Produced by Lucy Hatcher. Associate Producer, Jessica Kegu. Broadcast associate, Erin DuCharme. Edited by Robert Zimet.