Boeing Starliner hatch closed, setting stage for unpiloted return to Earth Friday

With its problematic mission finally winding down, Boeing's Starliner capsule was rigged for re-entry and its hatch closed Thursday, setting the stage for undocking and an unpiloted return to Earth overnight Friday in the final chapter of a disappointing test flight.

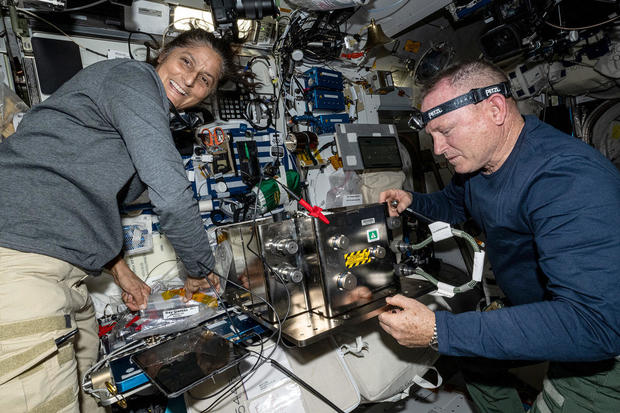

Ninety-two days after launching aboard the Starliner — a mission originally expected to last a little more than a week — commander Barry "Butch" Wilmore and co-pilot Sunita Williams kept their thoughts to themselves as the hatch was closed at 1:29 p.m. EDT.

Leaving Wilmore and Williams behind, the Starliner is expected to undock from the International Space Station's forward Harmony module just after 6 p.m. Friday. Five hours and 15 minutes later, the spacecraft's powerful braking rockets are programmed to fire for about 59 seconds to drop the ship out of orbit.

After a fiery southwest-to-northeast plunge across the Baja Peninsula, the Gulf of California and northern Mexico, the Starliner is expected to descend under its three main parachutes to an airbag-assisted 4-mph touchdown just after midnight at White Sands, N.M., where Boeing and NASA recovery teams will be standing by.

Astronauts' return delayed until February

Wilmore and Williams will return to Earth next February, hitching a ride home aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon ferry ship scheduled for launch Sept. 24. When they finally get back next year, they'll have logged 262 days in space.

On Wednesday, as she worked inside the Starliner helping arrange return items to ensure the right balance and center of gravity, Williams said "it's bittersweet to be packing up Starliner and putting our simulators in our seats. But, you know, we want to do the best we can to make sure she's in good shape."

She assured flight controllers "we'll tidy it all up tomorrow (Thursday), make sure everything's squared away and do a last couple of things for the closeout before hatch closure. Thanks for backing us up, thanks for looking over our shoulder and making sure we've got everything in the right place. We want her to have a nice, soft landing in the desert."

When Williams and Wilmore blasted off aboard the Starliner on June 5, they expected to be at the controls when the ship returned to Earth to close out its first piloted test flight. Boeing was equally confident the ship would be certified to carry long-duration crews to and from the station starting in early 2025.

But during rendezvous with the space station the day after launch, the Starliner suffered multiple helium leaks in its propulsion pressurization system and five maneuvering jets were "deselected" by the flight computer after exhibiting degraded thrust.

Boeing and NASA then began an exhaustive series of tests and analyses to determine what caused the problems and whether they might get worse or otherwise pose a threat to a safe re-entry and on-target landing.

Based on the test data, Boeing engineers concluded the problems were understood, would not get worse and that the Starliner could safely bring Wilmore and Williams back to Earth. They argued the departure and re-entry maneuvers would be much less stressful than what the thrusters experienced during the rendezvous.

But those jets are critical. They must fire as needed to safely move the Starliner away from the space station and then to keep it properly oriented and stable during the de-orbit rocket firing that will drop the ship out of orbit.

In the end, NASA managers did not accept Boeing's flight rationale, deciding too much uncertainty remained to risk bringing Wilmore and Williams down aboard the Starliner.

"We view the data and the uncertainty that's there differently than Boeing does," said NASA Associate Administrator Jim Free.

While different, more powerful thrusters are used for the actual braking burn, the smaller reaction control jets are needed to ensure the ship stays on the right trajectory to reach the White Sands landing site.

"Spaceflight is hard. The margins are thin. The space environment is not forgiving," said Norm Knight, director of flight operations at the Johnson Space Center. "And we have to be right."