Boeing, SpaceX to team with NASA on space taxis

Aerospace giant Boeing and newcomer SpaceX will share $6.8 billion in NASA contracts to build commercial space taxis to fly astronauts to and from the space station starting in 2017, ending reliance on Russia for access to low-Earth orbit and kick starting a new era of commercial space transportation, agency officials said Tuesday.

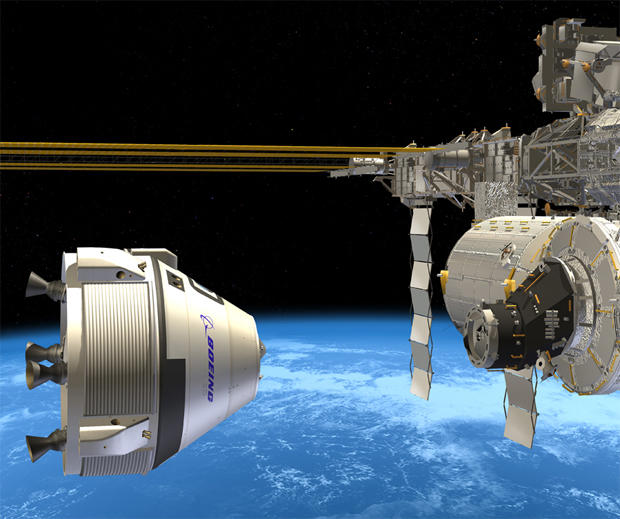

Boeing will receive a $4.2 billion Commercial Crew Transportation Capability (CCtCAP) contract to continue development of the company's CST-100 capsule while SpaceX will receive $2.6 billion to press ahead with work to perfect its futuristic Dragon crew craft.

"Today's announcement sets the stage for what promises to be the most ambitious and exciting chapter in the history of NASA and human spaceflight," said NASA Administrator Charles Bolden.

"From day one, the Obama administration has made it very clear that the greatest nation on Earth should not be dependent on any other nation to get into space. ... Today we're one step closer to launching our astronauts from U.S. soil on American spacecraft and ending the nation's sole reliance on Russia by 2017."

Left out in the cold was defense contractor Sierra Nevada Corp., which is developing an innovative winged spaceplane known as the Dream Chaser that, unlike its competitors, is designed to glide to a runway landing like a mini space shuttle.

Company officials have said they hoped to continue development of Dream Chaser with or without NASA money, but the company's near-term plans are not yet known.

It also is not yet known whether Congress will appropriate enough money to fund the development of two spacecraft or whether NASA will be forced to down select to a single provider at some point down the road. But Bolden said he was confident Congress will provide the funding necessary to keep SpaceX and Boeing on track for maiden flights in the 2017 timeframe.

Congress has appropriated about $2 billion for the commercial crew program since 2011, about a billion dollars less than NASA requested. The agency hopes to get around $800 million for the program in its fiscal 2015 budget.

In any case, the space agency now plans to begin NASA-sanctioned flights carrying astronauts to the space station in 2017, using either the CST-100 or a Dragon V2. Or both.

"Once NASA determines SpaceX and Boeing have met our requirements, the systems will be certified for NASA human spaceflight missions," said Kathy Lueders, manager of NASA's commercial crew program. "They will then conduct at least two and up to six missions under these contracts to deliver a crew of four to the International Space Station.

"These missions will also carry powered cargo and vital science experiments to the station and safely return them to U.S. soil. These missions will enable NASA and its international partners to perform more research, nearly doubling today's scientific research potential."

The new spacecraft also will be able to serve as lifeboats for station crew members, remaining attached to the station for up to 210 days at a stretch and "keeping our crew members safe in the event of an emergency," Lueders said.

Before regular missions begin, "Boeing and SpaceX will run their systems through rigorous ground tests," she added. "They also will perform at least one crewed flight test to the station with a NASA crew member aboard. During that flight test, they will demonstrate the ability to safely deliver crew and cargo, dock to the station and then return the crew safely home."

The new spacecraft will be the first American vehicles to carry astronauts on NASA-sanctioned flights since the space shuttle's last mission in 2011. And they will be the first built as a commercial endeavor that represents a break with normal NASA practice in a bid to lower the cost of access to space.

Just as important, supporters say, the spacecraft will end America's reliance on Russian Soyuz spacecraft for access to the $100 billion International Space Station. While NASA's use of Soyuz spacecraft will not end with the advent of U.S. space taxis, the agency will once again have independent access to low-Earth orbit using U.S. spacecraft launched from U.S. soil

"You can't really be a serious leader in space if you can't get your people there on your own spaceship," space historian John Logsdon, former director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, said in an interview. "The relationship with Russia has been successful, it's cost us less money than doing it on our own. If we were still flying shuttles, we'd be paying a hell of a lot more than the cost of seats on a Soyuz."

The commercial crew program "is both a real and symbolic indication that the United States is one of the leading space countries," he said.

Astronaut Barry "Butch" Wilmore is scheduled for launch next week aboard a Soyuz spacecraft bound for the station. In a telephone interview from Moscow last week, Wilmore told CBS News "it's vitally important to our nation going forward in space exploration. We want to be able to build our own rockets and launch from our own (soil)."

While the Russians have been good partners for NASA in the absence of a U.S. spacecraft "certainly we want to get back to that, we want to be able to do those types of things ourselves and we're working hard to get there. That's the big picture. From a personal standpoint, hopefully I get assigned for the first one!"

Boeing's CST-100 spacecraft is a state-of-the-art capsule incorporating weld-less fabrication, flight proven navigation software, powerful "pusher" escape rockets to propel the capsule away from a malfunctioning booster and a parachute-and-airbag landing system.

The spacecraft can carry up to seven astronauts and will be launched atop a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket, one of the most reliable boosters in the U.S. inventory.

SpaceX, owned and operated by entrepreneur Elon Musk, already holds a $1.6 billion contract to deliver supplies to the International Space Station with its uncrewed Dragon cargo ships.

Musk has made no secret of his personal ambition to help launch astronauts to low-Earth orbit and, eventually, to Mars, using a futuristic spacecraft known as Dragon V2 that he unveiled in July.

The crewed Dragon also would carry up to seven crew members, featuring pull-down flat-screen instrument displays, a powerful escape rocket system and sophisticated computer control.

"SpaceX is deeply honored by the trust NASA has placed in us," Musk said in a statement. We welcome today's decision and the mission it advances with gratitude and seriousness of purpose. It is a vital step in a journey that will ultimately take us to the stars and make humanity a multi-planet species."

The Dragon crew craft would launch atop SpaceX-built Falcon 9 rockets, boosters that Musk advertises for sale at around $60 million each. The United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket is powered by a Russian RD-180 first stage engine and goes for around $150 million per vehicle.

How that price disparity played into the unequal contract awards was not immediately clear.

But Musk has launched a wide-ranging attack on the Atlas 5, arguing its reliance on the Russian-built RD-180 makes it vulnerable to politics at a time when superpower relations are deteriorating. Musk also has filed a lawsuit protesting SpaceX's exclusion from Air Force contracts for near-term military missions using ULA's Delta 4 and Atlas 5 boosters.

How the RD-180 concern might have played into NASA's decision is not known, but Reuter reported Tuesday that United Launch Alliance and Amazon-founder Jeff Bezos' Blue Origin company planned to develop a new engine for the Atlas 5 that could replace the RD-180.

Both Boeing and SpaceX envision customers beyond NASA.

Boeing has partnered with Bigelow Aerospace, which hopes to build a commercial space station using inflatable modules that could serve as a base of operations for university researchers, space tourists and astronauts from non space-faring nations. Boeing managers have said the CST-100 would support Bigelow's ambitions if the company won the contract.

SpaceX also has grand plans for commercial exploitation of space, including eventual flights to deep space. Musk has said on multiple occasions that his long range goal is nothing less than the colonization of Mars.

"It's very important, not just that the United States is getting its independence back and is not going to be relying on the Russians, but we are, I don't know, what, 50 years kind of overdue getting the private sector involved in space," Joan Johnson Freese, professor of national security affairs at the U.S. Naval War College, said in an interview.

"To me, that's the bigger part of this puzzle. Anything related to space development that can be moved out of government hands and into the private sector is a step toward normalizing space. ... Anything that takes us closer to a normal pattern of development I think is a big deal."

The commercial crew and cargo programs are a direct result of the 2003 destruction of the shuttle Columbia during re-entry. In the wake of the disaster, the Bush administration ordered NASA to complete the space station and retire the shuttle by the end of the decade. In their place, the agency was tasked with developing new rockets and spacecraft for eventual flights to the moon and establishment of semi-permanent research stations on the surface.

NASA came up with the Constellation program to carry out those directives and began development of a Saturn 5-class super rocket to loft lunar landers and habitats and a smaller booster to launch crews on moon-bound missions or to the space station.

But the Obama administration ordered a dramatic change of course, opting to cancel Constellation and bypass the moon in favor of a "flexible path" architecture that called for two families of rockets and spacecraft with two different objectives.

NASA is now developing a heavy-lift rocket known as the Space Launch System, or SLS, that will boost the Constellation program's Orion capsule on crewed missions to retrieve and explore a small asteroid before eventual flights to the vicinity of Mars.

The first unpiloted test flight of an Orion capsule is planned for December. The first crewed mission is not expected before 2021.

But the SLS/Orion system is too expensive for routine use to low-Earth orbit. The Obama administration, in a bid to encourage development of commercial crewed spacecraft, supported a competition using NASA contracts to finance private-sector spacecraft that the government would then lease, or rent, for flights to the station.

"It's a little bit different than our traditional space flight programs in that we are transitioning some of the responsibilities over to the private sector," Phil McAllister, a senior NASA manager, told CBS News in a recent interview. "It used to be in a traditional NASA program, NASA would make almost all the decisions about the design, we would own and operate the hardware and we would be primarily responsible for its operation.

"In this context for commercial crew it's pretty much a public, private partnership," he said. "NASA is providing financial investment and our expertise and lessons learned to the companies who are really responsible for developing the hardware. It's really them making the decisions about the design. They are going to own and operate these systems and through this partnership, we hope to get safe, reliable and cost effective U.S. access to space, hopefully very quickly."

As the shuttle program was winding down, NASA envisioned a two-year gap between the end of shuttle operations and the debut of a replacement vehicle. That gap has stretched into six years, and possibly more, because of funding shortfalls and conflicting priorities in Congress.

Between 2011 and 2014, NASA requested $3 billion for commercial crew. Congress appropriated only $1.927 billion, according to Space Policy Online, a billion-dollar shortfall that has stretched out development and pushed the initial NASA-sponsored flights to 2017.

NASA has requested $848 million in its fiscal 2015 budget, but it's not yet clear how much the agency ultimately will receive. The House and Senate have not yet settled on a final number, but another shortfall of $50 million or more is expected.

Developing multiple crewed spacecraft -- Orion and now, the CST-100 and Dragon V2 -- has led to conflicting priorities on Capitol Hill. Supporters of the Orion/Space Launch System want to ensure steady funding to permit deep space exploration while protecting jobs in states like Alabama where the hardware is built.

Supporters of the commercial crew initiative argue it is crucial for NASA to end its reliance on the Russians for basic space transportation. Given the high cost of flying on a Soyuz -- more than $80 million a seat under the current contract -- and deteriorating superpower relations in the wake of Russia's actions in Ukraine, supporters say it is vital for the commercial crew program to receive full funding.

NASA started the competition to build a commercial crewed spacecraft in 2011, with the first in a series of contracts intended to encourage innovative designs for reliable, affordable transportation to and from low-Earth orbit.

The most recent contracts, awarded in 2012, gave SpaceX $440 million to develop detailed plans for launching the crewed Dragon capsule. Boeing won $460 million to develop plans for its CST-100 capsule while Sierra Nevada received $212.5 million to continue development of a winged lifting body that would land on a runway.

Many space insiders believed SpaceX would offer the least expensive alternative and a more innovative design while Boeing would provide the most reliability based on decades of space experience.

"Human space flight has been at our core since day one," John Mulholland, Boeing's commercial crew program manager, told CBS News in a recent interview. "In fact, every (U.S.) capsule that has taken United States astronauts to space has been a product that Boeing has developed in partnership with NASA."