Blue Origin stages spectacular abort test of spacecraft

In a simulated launch emergency, Blue Origin successfully tested the abort system built into its New Shepard sub-orbital spacecraft Wednesday, firing its escape motor 45 seconds after liftoff. The unpiloted spacecraft then deployed three parachutes as planned and settled to a gentle landing in a convincing demonstration of a critical safety system.

The New Shepard booster, meanwhile, surprised onlookers by continuing its ascent to the edge of space, despite predictions the abort motor’s powerful exhaust likely would overwhelm the rocket’s flight control system, leading to an expected crash landing.

Instead, the rocket continued what appeared to be a normal ascent, shutting down its main engine while passing through an altitude of 240,000 feet. The booster then plunged back into the atmosphere, deployed drag fins and aero brakes, re-ignited its engine and settled to a smooth, on-target touchdown two miles from its launching stand.

“There it is! There you go, New Shepard, look at her! What a test!” exclaimed launch commentator Ariane Cornell. “What an extraordinary test, and a tremendous final flight for both craft. As we very optimistically aimed for, our crew capsule successfully executed its in-flight escape test, and the booster brilliantly continued to space and came home for a fifth landing.”

Blue Origin, owned by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is developing the reusable New Shepard system to routinely carry up to six space tourists, researchers and/or experiments on brief sub-orbital flights above the discernible atmosphere some 62 miles up, the somewhat arbitrary “boundary” of space.

Once separated from the booster, passengers will experience four to five minutes of weightlessness before falling back to Earth, enjoying a spectacular view of of the planet’s curved limb through the largest windows ever designed for spaceflight.

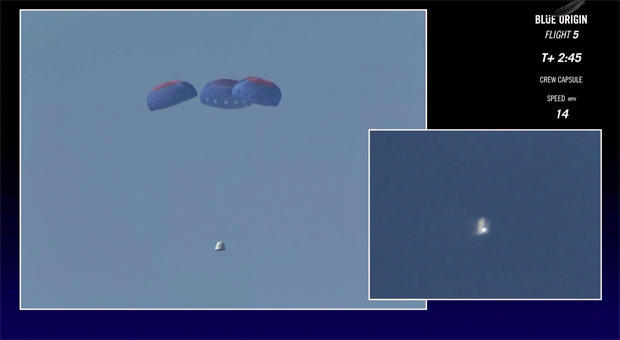

As the capsule slams back into the dense lower atmosphere, passengers will experience up to 5 Gs of deceleration before three small drogue chutes deploy to stabilize the spacecraft. Then, three main chutes deploy and small retro rockets fire an instant before touchdown to reduce the landing velocity to just a few miles per hour.

The reusable New Shepard booster, powered by a single hydrogen-fueled BE-3 engine developed by Blue Origin, is designed to release the capsule near the apex of its trajectory and then to descend back to the launch site, re-igniting its engine for a powered vertical touchdown on deployed landing legs.

The test Wednesday got underway at 11:36 a.m. EDT (GMT-4), about a half hour behind schedule. The rocket climbed smoothly away from its firing stand and quickly accelerated as it consumed its propellants and shed weight. Just 45 seconds after liftoff, at an altitude of about 16,000 feet, the abort system was triggered.

It was the first test of the capsule’s abort rocket during an actual flight, during the most dangerous portion of the trajectory when atmospheric pressure on the vehicle is at its maximum.

The abort motor quickly pushed the crew capsule away from the New Shepard booster. Bezos wrote earlier this month that he expected the abort motor’s exhaust plume to destabilize the booster, making a crash landing likely. But the booster appeared remarkably stable throughout the test and continued its ascent.

NASA’s Mercury and Apollo spacecraft, along with Russia’s Soyuz crew capsule, were designed to utilize throw-away solid-rocket motors mounted above the crew capsule that could pull a crew to safety. Unused escape motors and towers were jettisoned late in the ascent.

New Shepard also relies on a solid-fuel motor, but one that is built into the capsule and pushes from below, generating a near-instantaneous 70,000 pounds of thrust during a two-second burn. The design means the abort system does not have to be replaced between flights if it is not activated.

Blue Origin has tested the abort system before, launching a capsule from the ground using the pusher motor. But Wednesday test was the first carried out from a climbing rocket under actual flight conditions.

When the abort motor burned out, the capsule deployed three small drogue chutes and then its three main parachutes, allowing it to settle to a picture-perfect landing, apparently none the worse for the wear.

While detailed analysis of telemetry is not yet complete, the “pusher” abort system appeared to work as designed, demonstrating how a crew could be propelled to safety in the event of a major booster malfunction -- a key milestone in the spacecraft’s development.

It was the sixth test flight of a reusable New Shepard booster overall -- the first test rocket did not survive its landing attempt -- and the fifth in a row by the rocket launched Wednesday.

“We’d really like to retire it after this test and put it in a museum,” Bezos wrote earlier this month. “Sadly, that’s not likely. This test will probably destroy the booster.”

Remarkably, the booster survived its final test with no apparent difficulty.

“The booster is very robust and our Monte Carlo simulations show there’s some chance we can fly through these disturbances and recover the booster,” Bezos wrote. “If the booster does manage to survive this flight – its fifth – we will in fact reward it for its service with a retirement party and put it in a museum.”

The New Shepard sub-orbital rocket is just one of the space projects being financed by Bezos and Blue Origin. The company is in the process of building a sprawling factory just outside the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to build much larger rockets designed to boost payloads, and eventually people, into orbit.

The New Glenn rocket will be powered by Blue Origin’s more powerful BE-4 engine, burning liquid oxygen and liquefied natural gas. Seven of the engines will power the New Glenn booster’s first stage while a single engine will power the second stage. A three-stage version, standing 313 feet tall, will use a BE-3 powered third stage.

Blue Origin has leased a retired launch complex at the nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station to test the new engine and to launch the New Glenn and follow-on boosters. The sub-orbital New Shepard will remain based at the company’s McGregor, Texas, flight test facility.

The BE-4 at the heart of the New Glenn rocket is the leading candidate for powering the first stage of United Launch Alliance’s new Vulcan booster, which ULA is developing to replace the company’s workhorse Atlas and Delta rockets. Initial test firings of the BE-4 are expected before or just after the end of the year.

Like the New Shepard rocket, the New Glenn will feature a reusable first stage that will fly itself to touchdown on an off-shore barge or on a landing pad near the launch site. SpaceX already has successfully demonstrated both milestones using its Falcon 9 orbital rockets.