Black family works to restore roughly 200-year-old cemetery in Texas to reclaim legacy, honor ancestors

The continuing fight for social justice is giving new life to community efforts to preserve Black cemeteries. Congress is considering legislation that would create a database of burial sites, and provide funding to research and protect them.

This could bolster cemetery restoration projects across the country, including one from CBS News producer Rodney Hawkins, who is embarking on a journey to reclaim his family legacy.

Deep in the piney woods of East Texas, beneath a roughly 200-year-old overgrown cemetery, is Hawkins's family history and a part of America's buried past.

"I had to work the fields just like everybody else. I had to pick cotton," Carolyn Curl-Hurd, Hawkins's grandmother, told him.

Asked why she picked cotton if she didn't grow up in slavery, Curl-Hurd said, "Well, my dad — that was part of what he did to make a living for the family."

Curl-Hurd was born in 1946 on a sharecropping farm. Her parents, Mitch and Ova Curl, raised 12 children in a tiny house in Nacogdoches, the oldest city in Texas, on their more than 100 acres. The family still owns most of the land.

Not far from the property, they found their family cemetery in disarray.

"It's tragic to see this cemetery in this state," Hawkins said. "As painful as it can be to uncover the past, it's important my ancestors, our ancestors are honored."

Hawkins's cousins Rayford and Nell Coleman want to make sure that happens. "It needs a lot of work," Rayford said about the cemetery.

Nell, who has gone through chemotherapy and had a stroke in 2016, said death has hit her "right in the face."

"We all need to think about how we want our family to not forget us," she said.

"You're the young generation," Nell told Hawkins. "And my kids. … We have to make them aware of the history before us."

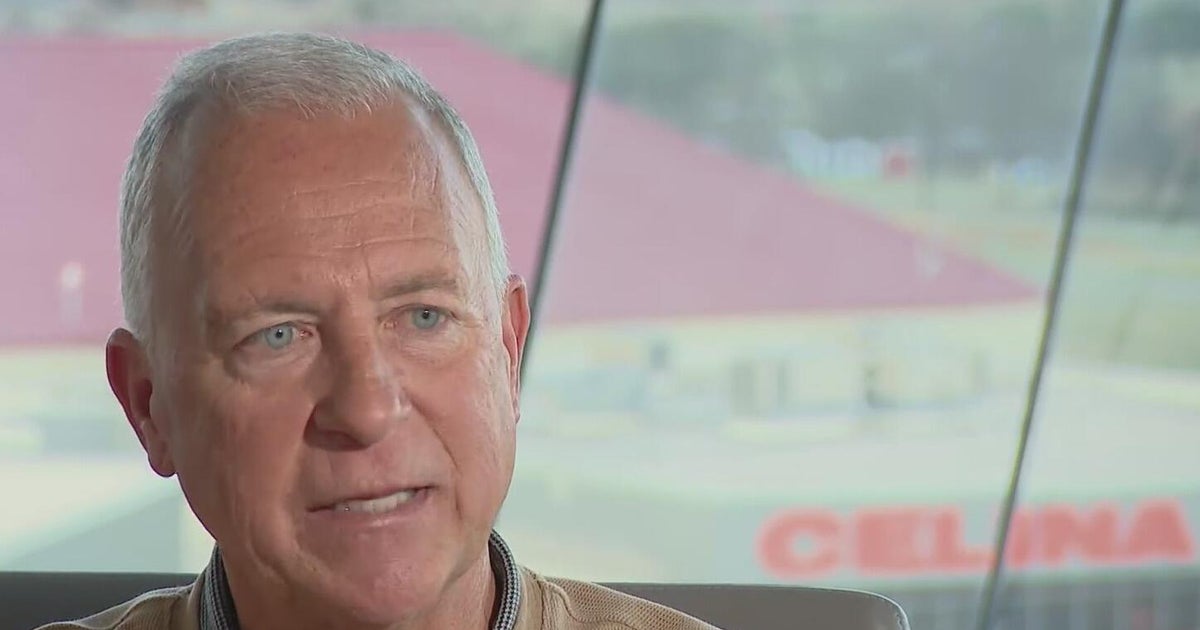

The family had to reclaim the cemetery to not lose their history. The state officially registered Old Mount Gillion this summer with the help of Archie Rison.

"It's ugly history but it's necessary that we talk about it," Rison said.

He's devoted his retirement to restoring historically Black cemeteries. "I'm connecting myself to my past. A lot of people, a lot of Black folks can't do that. And some, they tell me, my friends, they don't want to," Rison said.

Some want to forget the pain and shame of this country's past, he said.

"When slaves were free, they knew the pains that our ancestors went through," Rison said. "And the biggest thing on their minds was survival."

Rison introduced Hawkins to Perky Beisel, a history professor at Stephen F. Austin State University, who works with the Texas Historical Commission to preserve cemeteries. Beisel and her students joined Hawkins to start the restoration, a year-long project.

Beisel said a tombstone for Hawkins's great-great-grandfather Bill Curl, whose parents were enslaved, has great significance.

"This was well done," she said about the tombstone. "This is a true sign to anybody walking by this is an important person."

Curl-Hurd hadn't been to the cemetery in over 40 years.

"You don't think that when you're growing up the value of what your parents are teaching you until you look back. And it's — it was wonderful," she said.