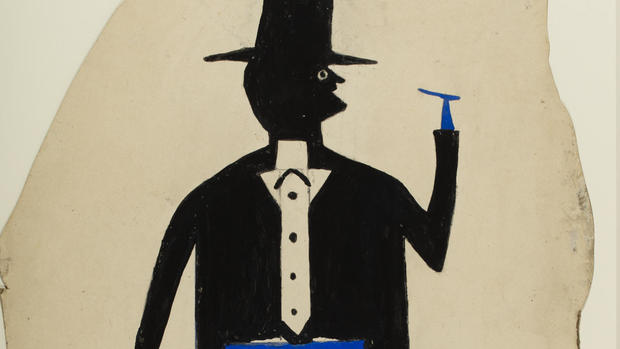

Bill Traylor: The imaginative art of a freed slave

Bill Traylor had a story to tell, so he put it down on paper. He was born into slavery around 1853 in rural Alabama, and after the Civil War and Emancipation he remained on a plantation working as a sharecropper for nearly five decades. In his 80s, he moved to the city of Montgomery, but soon found himself without work and homeless.

Around the age of 86, when most people have slowed down, Traylor – unable to write anything other than his name – began to paint and draw.

"It was a hard-earned life," said Leslie Umberger, curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., which is holding a retrospective of Traylor's art – 155 paintings and drawings, much of it created on paper, paperboard, pieces of found packing, candy boxes, or anything he could find.

"It's a brilliant body of work, because it records this time in a place, but it's more than a record; it's this personal expression, and it's lyrical and it's beautiful and it's incredibly moving."

"This is a man who lived through slavery, extraordinary oppression, Jim Crow, the Great Migration," said correspondent Chip Reid.

"That's true; Traylor really spanned this incredible moment in American history," said Umberger. "Slavery and civil rights get a lot of attention, and then that time period between often gets less. But that is the peak years of lynching in America. This is Ground Zero where Traylor lived, where all of this is happening around him."

Yet, despite one drawing of a lynching, Traylor was usually not precise in depicting violence. "Most of the time he backed off of that kind of really clear-cut narrative," Umberger said. "For a black man to be making a commentary on things that he had been witness to in this time and place, this would have been an image that could have gotten him in a lot of trouble."

Instead, he depicted flat, simplified forms, none as straightforward as they seem at first glance. "Dogs are recurring characters in Traylor's work," said Umberger. "Sometimes they're very little and they're very sweet, and other times they're this big, hulking, scary animal. What I think is going on here is maybe this metaphor for slavery, or disempowerment in general, the black population kind of always being held in bondage by social agency and wealth."

Reid asked, "What do you say to people who say, 'It looks so simplistic, it looks like a child could do it'?"

"Well, Traylor taught himself," she replied. "His forms are arguably simple. But that's also the power of the work. He's putting down what he needs to, and not very often more than that. He's coming up with his symbolisms and his ways of distilling the very complicated things around him in a way that's personal and unique, but absolutely innovative, and his."

During his lifetime Traylor's work gained some local attention, but failed to gain traction with the larger art world. He died in 1949 around the age of 96, leaving behind hundreds of works. Seventy years later people are lining up to hear the story he needed to tell.

Umberger said, "In his final days, he took it upon himself to leave a record saying, 'I was important. I had a point of view and I did matter.'"

For more info:

- "Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor" at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (through April 7)

- Exhibition Catalogue: "Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor" by Leslie Umberger (Princeton University Press), in Hardcover format, available via Amazon

- Bill Traylor (artnet.com)

Story produced by Sara Kugel.