President Biden talks tough about winning on green energy. But China is already ahead in one critical area.

When speaking about competition with China, President Joe Biden can sound as if he's taken the mic at a pep rally.

"They think they're gonna win. Well I got news for them, they will not win this race. We can't let them," Mr. Biden said during his remarks Tuesday at the Ford Rouge Electric Vehicle Center in Dearborn, Michigan.

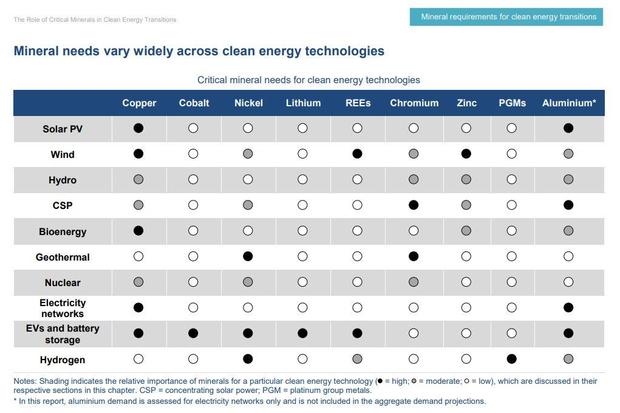

The "race" is the competition to produce green energy technologies. Global superpowers are vying to dominate the critical minerals market — the raw materials such as copper, nickel, lithium, zinc and rare earth elements that are the building blocks of this century's energy sector. These minerals are used in electric vehicles, solar panels and wind turbines, as well as smartphones, robotics and military equipment.

"We've got to take over the world market," Mr. Biden told one employee while touring the Ford facility Tuesday. But experts say America is far behind.

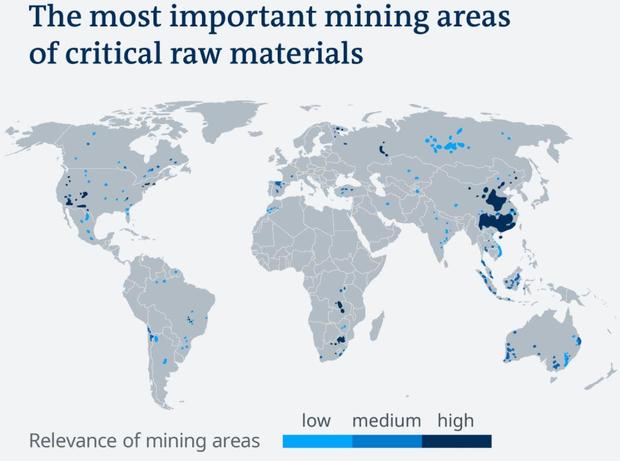

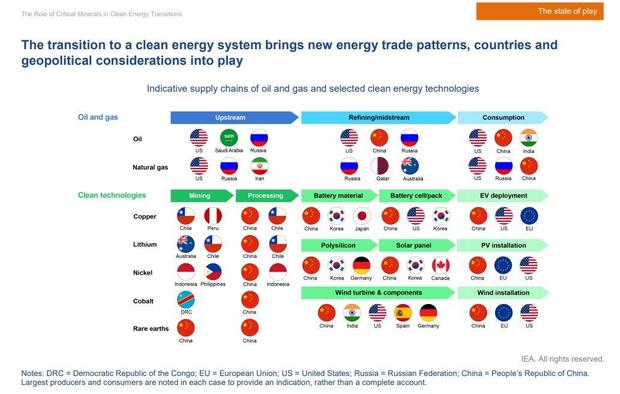

The United States is the world's second leading supplier of critical raw materials, supplying 7% of the global market, according to the European Commission. But China, with mining access to two-thirds of the world's critical minerals, leads by far, supplying 45%.

China also leads in processing these materials, commanding the supply chain upwards to manufacturing and downwards to consumers. Their power is fortified by putting African children and political prisoners to work, while adhering to poor environmental standards.

Given the economic opportunity as green technologies become more popular, many nations, most notably the U.S., are beginning to try and challenge China. That change could fortify and diversify supply chains, but add tension to geopolitics.

An International Energy Agency report from earlier this month showed the "looming mismatch between the world's strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals," said Fatih Birol, the agency's executive director.

Electric vehicles use six times the mineral resources of traditional cars. An onshore wind plant needs nine times the mineral input than a comparable sized gas-powered facility. And demand for lithium batteries alone could grow 30 times current rates by 2040. The agency predicts that for world economies to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the need for critical minerals in the energy sector could increase sixfold.

In order to bridge that gap, the report stated major powers should cooperate and work together to mine and process critical minerals, not against one another.

"The challenges are not insurmountable," said Birol. "By acting now and acting together, they can significantly reduce the risks of price volatility and supply disruptions."

Attempting to merely counterbalance China's dominance is a lofty challenge for the Biden administration, a point stressed in a report from the bipartisan nonprofit Energy Innovation Reform Project.

"Alone, either the energy transition or growing competition would be sufficient to preoccupy U.S. officials and members of Congress across multiple administrations. Together, these two challenges will test the United States even as they offer opportunities to renew America's role as an innovator, accelerate economic growth, strengthen national security, and sustain U.S. international leadership."

The project's report advocated working with U.S. allies such as Japan, South Korea, India and the European Union to build more critical mineral supply chains. Paul Saunders, the group's president, said establishing a multilateral organization, similar to the International Energy Agency, which emerged in the wake of OPEC's 1973 oil embargo, could facilitate coordination among the U.S. and other advanced economies, increase standards, and level the competitive playing field with China.

While a February executive order aimed at fortifying the country's critical minerals supply chain included collaboration with allies, Mr. Biden's public statements have positioned the U.S. and China in opposing corners on energy innovation.

Saunders told CBS News that Mr. Biden's language has been "careful" and could be a tool used to unite policy makers and sell his plans by advertising their pro-American benefits.

"The problem, of course, is that many other people are also going to use those arguments. And many of them will be less careful in their use of language," he said. "Competing with China: Yes. Having constant crises and conflicts with China: No."

But the U.S. has long framed the future green energy transition "in bipolar terms," said Sophia Kalantzakos, an environmental and public policy professor at New York University, calling Mr. Biden's repetitious anti-China sentiment "counterproductive".

The American approach to fortifying the critical mineral supply chain has ramifications economically in the U.S. and abroad, and geopolitically as the world shifts to green-based economies. Kalantzakos said these goals make nations more interconnected than ever, making it impossible for the U.S. to entirely decouple from China and dominate the critical mineral industry.

An example of that interconnectedness is China's "Belt & Road'' initiative, created in 2013 to forge trade relationships with nearly 70 countries throughout Eurasia, Africa and South America.

At a White House event on domestic semiconductor and battery supply chain resilience last month, the president said lagging behind on technologies of the 21st century was "not American."

Mr. Biden's blunt anti-China rhetoric could be a means to corral congressional support, said Jane Nakano, senior fellow in the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. But Nakano said the president's rhetoric could place stress on U.S. allies.

"Certainly the European economies are quite concerned this bilateral tension between Washington and Beijing could really damage their own economy, but also [their] climate agendas," she said.

Ultimately, anti-China rhetoric and policy can have national security ramifications. The U.S. can work with allies to build supply chains that rival China's, but that will take decades. In the meantime, a disgruntled Chinese government could withhold materials from other countries — as they did with Japan in 2010 — potentially bringing the president's plans to install green energy technology across the country to a halt.