Bernie Sanders has a way to raise $2 trillion -- tax Wall Street trading

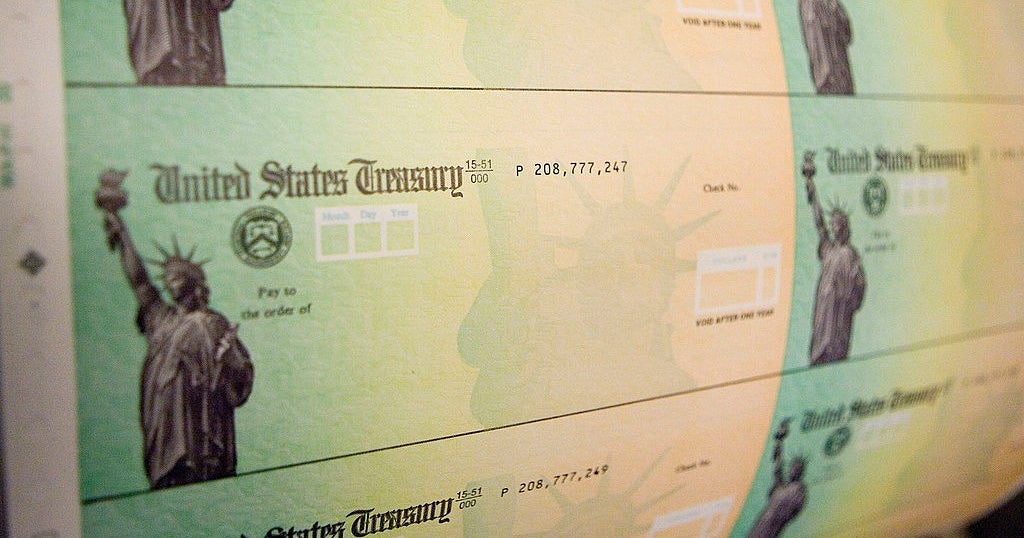

- Sen. Bernie Sanders has introduced a bill that would tax trading of stocks, bonds and derivatives at rates ranging from 0.005% to 0.5%.

- A so-called financial transactions tax could raise between $776 billion and $2.4 trillion over 10 years, economists estimate.

- The U.S. hasn't taxed financial trades since the 1960s, although the 2008 financial crash brought the idea back in vogue.

Sen. Bernie Sanders has put "Medicare for All" and free public college at the center of his 2020 presidential campaign, and he knows just who should pay for the federal programs: Wall Street. The Vermont independent this week proposed a bill that would impose a small tax on trades of stocks, bonds and derivatives.

Under the measure, any stocks traded would be taxed at a rate of 0.5%, bonds at 0.1% and derivatives at 0.005%. So selling $1,000 of stock would incur a tax of $5. Such a tax could conservatively raise tens of billions of dollars per year, according to the Congressional Budget Office, which estimated the potential revenue at $776 billion over a decade. A 2017 study by the University of Massachusetts concluded a so-called financial transactions tax could yield a far bigger bounty -- $2.4 trillion over 10 years.

"While the top 23 banks in America received over $20 billion in tax breaks last year as a result of the Trump tax plan, hundreds of thousands of young people are unable to go to college because they can't afford it, 34 million Americans have no health insurance, one out of five Americans can't afford to buy the medicine prescribed by their doctors, over 40 million Americans are living in poverty," Sanders said in introducing the legislation.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand is a co-sponsor of the bill; Rep. Barbara Lee, D.-California, is sponsoring the legislation in the House, where it enjoys support among the Democratic party's left flank.

The idea of a financial transactions tax isn't new. Dozens of such proposals have been bubbling since Wall Street's meltdown in 2008 plunged the U.S. into a multi-year recession, with a similar bill introduced this past March. But the policy goes back much further.

Sanders noted that Great Britain has levied such a tax since the late 17th century, while dozens of other countries also use one. In more recent years, France started taxing trades in 2012, and a wider tax went into effect in the European Union in 2017. The U.S. itself employed a transactions tax from 1914 until 1966, when it was eliminated as part of a broader tax cut. Meanwhile, the Securities and Exchange Commission, which regulates some financial products, funds itself via a small tax on entities that trade these products.

Tamping own speculation?

Economists from Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz to former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers have made the case for such a tax. The finance industry opposes it, arguing that it would hurt average investors who would have to pay more to invest or have to make fewer trades.

In fact, research suggests a transaction tax would have the greatest impact on hedge funds and other speculators, which make hundreds or thousands of trades a second, profiting from faster technology or advance information. (In one such instance, high-speed traders paid tens of thousands of dollars in monthly fees to Business Wire in order to get direct access to market-moving press releases, giving them a split-second advantage over competitors.)

While each trade might yield only a fraction of a cent in profit, the sheer volume of trades make it lucrative. Nearly half the volume on a given day is made up of this type of speculative activity, MarketWatch reported in 2017.

Supporters of a Wall Street tax point to this reduction in speculation as a benefit. It's "skimming the fat off of a sector of the economy that can afford to pay it," the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research wrote during the Great Recession. A Forbes contributor likened it to a cigarette tax: "It would pick up some revenue while discouraging dangerous activity," she wrote.

For the relatively few middle-class investors who might get dinged, the Sanders bill has a carve-out. Any taxpayer earning less than $50,000 whose investment adviser passes on the cost of the trading tax could get the full amount back as a tax credit.