Nearly 100, WWII veteran Ben Skardon marches on

Every spring, thousands of soldiers and civilians from across the country descend upon the desert mountains of New Mexico for the Bataan Memorial Death March, a rugged 26.2 mile marathon that some run and others walk. The event commemorates the infamous forced march of American and Filipino soldiers by the Japanese Army that killed thousands on the Bataan Peninsula during some of the darkest days of World War II.

A disproportionate number of the American prisoners were from the New Mexico National Guard. It's why the memorial march is held annually at White Sands Missile Range in southern New Mexico. Like many soldiers, past and present, Colonel Ben Skardon takes part for the historical symbolism. We first aired this story last year, and decided to run it again this Memorial Day weekend. What makes him unique is that among all the participants in New Mexico, Ben Skardon is the only survivor of the actual Bataan Death March. And one more thing: he is nearly 100 years old.

Sharyn Alfonsi: At 98 years old, what keeps you going?

Ben Skardon: It doesn't take anything to get me going, I tell ya. I wake up in the morning and say, "Let's go!"

It's become a tradition: Colonel Ben Skardon arriving a half hour before sunrise in his orange Clemson jacket, as the corrals fill up with soldiers and American flags. Many will carry backpacks weighing 35 pounds or more on the course. A few will be testing new limbs.

"That's my Mecca. It became a place where I'm supposed to think about what went on during the march."

Before the Bataan Memorial Death March begins, there is a ceremonial roll call. For those who survived the real thing in 1942 and who have come to brave the cold New Mexico morning, Ben Skardon is the only one who marched then and will march now, into the desert of white sands.

Ben Skardon: That's my Mecca. It became a place where I'm supposed to think about what went on during the march.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is it good to remember? Cause no one would blame you if you never wanted to think about that march again. But…

Ben Skardon: Oh. No, ma'am. That's indelible in my mind.

The arduous course that awaits him is an indelible reminder of the haunting procession of starving American and Filipino soldiers who were ordered to walk 66 miles by the conquering Japanese army. It was a march to the grave, thousands died along the way. The Bataan Death March, as it became known, is considered one of the most notorious crimes of World War II; 74 years later in New Mexico, Ben Skardon calmly watches as all 6,000 runners and marchers leave the starting line and then he begins his pilgrimage.

He hopes to walk the marathon's first eight-and-a-half miles as a tribute, just as he has done eight times before, under the gaze of the Organ Mountains. He's accompanied by what's called Ben's brigade, a band of 25 friends, family members and former students of this longtime English professor at Clemson University. An Army medic and an ROTC cadet hover nearby, as do support vehicles, just in case…when you're 98, walking at an altitude of 4,000 feet, every mile marker can seem like a landmark, but the colonel is in no mood to linger.

Ben Skardon: We'll rest here 10 seconds…1, 2, 3… 10…Oosh!

Oosh…it's what Ben remembers the Japanese guards bellowing when they wanted their American and Filipino prisoners to keep moving on Bataan. Ben keeps moving in New Mexico.

Over gulleys and sandpits, after passing mile two, he breaks into a rhythm and song. Water stations are named for towns along the Bataan Death March. Volunteers have learned to wait for Ben so they can pay their respects. In April 1942, in the earliest months of the war, Ben Skardon was an Army company commander in the Philippines. After four months of fighting, 76,000 outgunned and cornered American and Filipino troops were surrendered to the invading Japanese Army, the largest surrender in American military history. The prisoners massed at the bottom of the Bataan Peninsula, which sticks out like a thumb along Manila Bay.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Where did you think you were going?

Ben Skardon: I didn't have the slightest idea. I, geography-wise, I, all I knew was Manila would be at the end of the Manila Bay. And I thought we will probably end up in Manila Hotel.

The Japanese guards thought surrendering was beneath a soldier. They held their prisoners in contempt, streams of Americans and Filipinos were herded along the old national road in 95-degree heat, the sun searing their skin. Skardon was already suffering from malaria when they first started walking, but he couldn't stop or slow down, not with the threat of Japanese bayonets.

Ben Skardon: That was the greatest fear on the marches, the bayonet.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Did you see people get bayoneted?

Ben Skardon: No. But one got bayoneted right behind me. Then I was outta there, and I was terrified.

There were atrocities he couldn't miss…

Ben Skardon: There were two in the middle of the road, Americans. And they had been run over so many times.

Sharyn Alfonsi: By trucks…

Ben Skardon: So many times that they were flattened out. And it, you know how you cut out a silhouette of somebody? It looked like they were cardboard. You could pick them up.

Today, commercial traffic lines Bataan's old national road, but the death march is remembered with signposts, little monuments to the struggle the prisoners faced as they walked through the mountains and low-lying villages. Always they headed north. Skardon wondered if they would ever get there, wherever there was.

Ben Skardon: And all I was just wishin' was somewhere we could stop. That's one of the miracles that happened to me, is to be in the condition I was in and to make the march and to not even sometimes know whether it was day or night because you just trudged along.

Prisoners dropped dead by the hour. Food and water were scarcer than Japanese empathy…

Ben Skardon: But I had with me a can of Eagle condensed milk.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Where'd that come from?

Ben Skardon: And I don't know where it came from, but it was in my pocket. And I put my can of milk in there and held onto it the whole time. So at night, I pulled that out. I didn't show it to anybody. And I would suck on it a little bit. You know, saliva go down your throat. Ooh, that was great!

"Now, when I tell you somethin' saved my life, it saved my life. That's not a cliche with me."

Sharyn Alfonsi: So that milk really sustained you?

Ben Skardon: I feel that saved my life. Now, when I tell you somethin' saved my life, it saved my life. That's not a cliché with me.

Every time he marches in New Mexico, Ben Skardon carries an emblematic can of condensed milk, as if it's a family heirloom. As the temperatures rise dramatically, the long sandy path can start to seem endless. But for Ben, marching in this setting, at his own pace, with no bayonet in sight, is liberating.

Ben Skardon: Out here, you look wide, there's not a fence in sight, no guards. You could almost say there's immense freedom. It's also about people that I knew who were like brothers to me and not a single one of them got back. I'm very lucky and this is something to me that is obligatory.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Obligatory?

Ben Skardon: Yes, I'm obligated to be here, to them. They aren't here of course.

They are Henry Leitner and Otis Morgan, fellow prisoners and fellow Clemson graduates, who cared for Skardon after the death march finally came to an end, eight days after it had begun. The finish line for the American captives was a disease-infested prison camp in the Philippine countryside, where Ben Skardon became gravely ill. On top of his malaria, Ben was afflicted with beriberi due to a severe vitamin deficiency.

"I like to say, 'I'm walkin' for ya, Henry, Otis.'"

Ben Skardon: The danger of the beriberi was that it came up your legs. It got to your heart, it kills you. Your feet were so sensitive, nothing could touch 'em without you doing like that, see. Henry would get hold of my feet. And then every time I jerked, he would squeeze. Well, he would do that for hours. Time meant nothing.

Otis, who spoke some Japanese, came up with a plan: the bait was Ben's Clemson class ring of 1938. He wears a replica today. On the farm where the prisoners worked as slave labor, Otis approached a Japanese guard to make a deal.

Ben Skardon: Well, Otis let it be known through the guard that he knew of a gold ring, would trade for food. So Otis came in from the work detail and with a live chicken, pullet-size, very thin.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You ate it all?

Ben Skardon: And then they boiled it in a pail and then they take that chicken and broth and rice. Man, that's great stuff!

Nourished again, Ben recovered.

Ben Skardon: Something restoreth my soul. Things that were done for me, I could never thank 'em enough.

Ben never got to repay Henry and Otis. Late in the war, the unmarked ships they were crammed into en route to POW camps in Japan were hit by American bombers, twice. Ben survived both times, Otis did not. Henry died of pneumonia in a Japanese POW camp.

Ben Skardon: And if, if I could have cried, I would have cried.

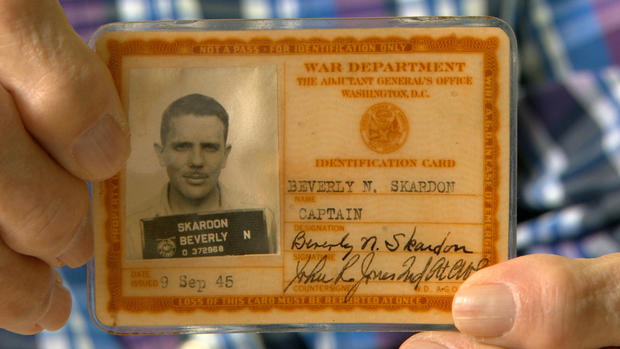

All together, Ben was a prisoner of the Japanese for over a thousand days. He was finally liberated from a camp in Manchuria, China, by the Soviet Army in August 1945. This is the first picture that was taken of him after he was freed. Beverly is his given name.

Sharyn Alfonsi: That was a happy guy in that picture. Yeah, you look very thin here.

Ben Skardon: Well, I wasn't asking for compliments.

He came home to South Carolina and taught English at Clemson, where he was beloved by his students. But few knew what he had endured.

Ben Skardon: I never spoke about it until I was 80 years old. I felt humiliated.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Humiliated.

Ben Skardon: We had surrendered. Yes, ma'am. I, that was one thing that I had a hard tug with in my own mind. We surrendered. We gave up.

It doesn't matter that he was awarded two Silver Stars and two Bronze Stars for gallantry and heroism in combat on Bataan.

Sharyn Alfonsi: When you came back to the United States, did you feel like a hero?

Ben Skardon: Don't even say that word in my presence. I'm not a hero. It's not how much you suffer. That's not, doesn't make you a hero.

Just outside Clemson's football stadium sits Memorial Park. Etched in the cobblestones, are the names of Clemson graduates who were killed in war.

Ben Skardon: They are the true heroes I suppose you could say…

Among them, Otis Morgan and Henry Leitner, the two men who saved his life. Ben likes to visit often, and plant little American flags by their names.

Ben Skardon: To me, there's a certain wonderment about my being here.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do you account for the fact that, you know, you were so sick, and you made it home and these guys didn't?

Ben Skardon: It remains a mystery. But I feel like that comes up when I walk out there. I like to say, "I'm walkin' for ya, Henry, Otis."

More than three hours after Ben started, as he approaches the seven-mile point on his journey, his own finish line within reach, there are reminders that suffering and valor in war don't belong to just one generation. All throughout the day, runners and marchers grind their way around the mountains and to the finish.

Twenty-six miles is too much to ask of a 98-year-old. Long ago, he determined that eight-and-a-half miles was his outer limit, but for the ninth time, Ben Skardon completes his personal march a half hour faster than the year before.

Ben Skardon: It's just a warm, terrific feeling…

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you think you'll do it again?

Ben Skardon: If I'm in this condition, I'll be here next year…I can't turn this place loose.

Ben Skardon did it again two months ago at age 99. He turns 100 on July 14th and hopes to march in New Mexico next spring.

Produced by Draggan Mihailovich. Laura Dodd, associate producer.