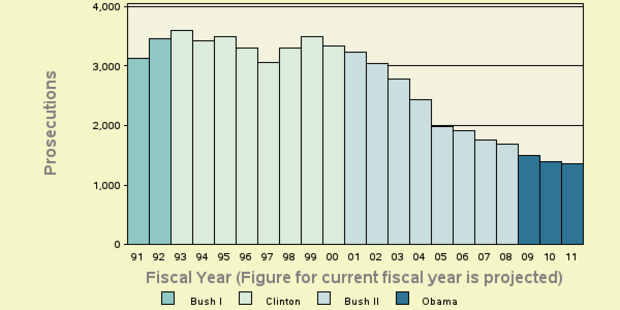

Bank prosecutions drop as bank failures rise

COMMENTARY: Don't hold your breath waiting for someone to get charged in the collapse of MF Global, or any other financial institution. In the last 10 years, prosecutions for fraud at financial institutions has dropped by nearly 58 percent. In the last five years, as bank failures have skyrocketed, prosecutions have dropped 28 percent.

In 2000, Bill Clinton's last year in office, there were more than 3,000 federal prosecutions for fraud at financial institutions, according to a report by Syracuse University's Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). That year the FDIC reported seven bank failures. Prosecutions have dropped every year since then. In 2010, when there were 157 failures, the number of prosecutions had dropped below 1,500.

During the first 11 months of the 2011 fiscal year, the feds filed 1,251 new prosecutions. If that pace continues, TRAC projects a total of 1,365 prosecutions for the fiscal year. So far this year, there have been 88 bank failures.

Although the rate of decrease has slowed slightly under the Obama administration, this looks like yet another area where he is continuing the policies of his predecessor.

It's worth keeping in mind that these prosecutions aren't limited to banks. Federal law defines a "financial institution" as anything from a bank to a pawnbroker to a car dealer to someone involved in real estate closings and settlements.

Many reports have shown this is the result of an increasing unwillingness to prosecute these cases. Some of this is because they are very complex and federal prosecutors frequently don't have the resources to build a case. However, there is also plenty of anecdotal evidence that prosecutors have been told not to go after bankers because of perceived risk it might pose to the already-shaky financial system. (What, does someone really think the public's opinion of bankers could get worse?)

A few months ago we were told that criminal investigations of IndyMac, and New Century Financial and Washington Mutual were officially going nowhere. Earlier this year, the U.S. Attorney's office in Los Angeles closed its investigation of Countrywide Financial with no charges filed.

But wait, there's more - well, make that less. The Justice Department has brought exactly three cases against employees at large financial firms and 0 (zero) against executives at large banks. (It is worth remembering that the feds didn't catch Bernie Madoff; he turned himself in.) Apparently federal prosecutors are playing the same role for large banks that the ratings agencies once played.

We now have the privatization of white collar crime, where the only punishments handed out come as a result of private civil actions. Unfortunately, as New York Times reporters Louise Story and Gretchen Morgenson wrote, "The lack of criminal inquiries by the government means that restitution is often paid by innocent parties -- shareholders -- who have already been hurt by the questionable conduct."