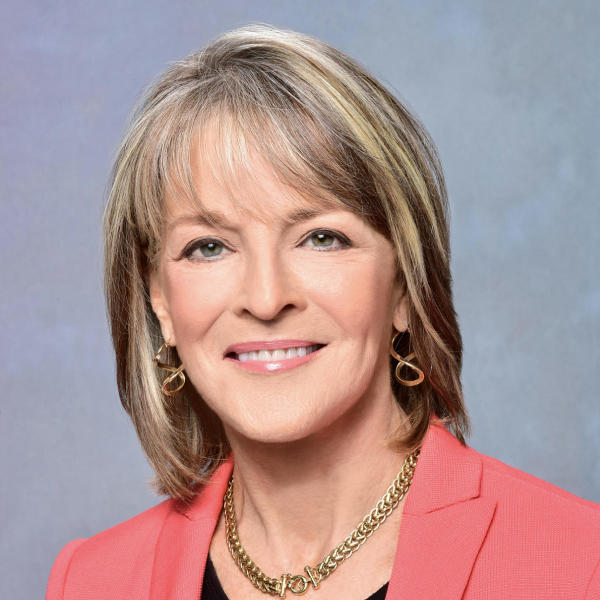

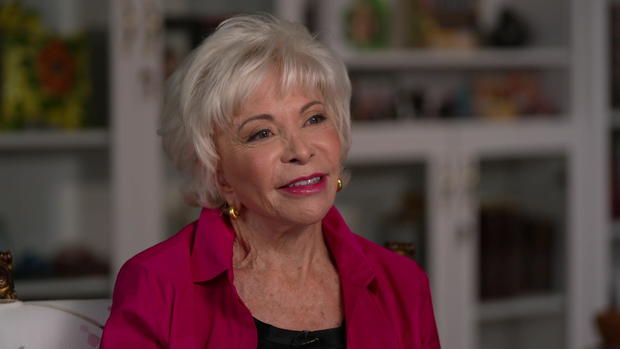

Author Isabel Allende on how writing "gave me a voice when I had no voice"

If anyone knows what it takes to capture readers' attention, it is Isabel Allende. The 80-year-old writer has filled more than two dozen books with passionate and courageous characters, selling more than 74 million copies, translated into some 40 languages. "I have the book in my head, the characters in my soul, all the time," she said. "You need crazy people, and you need people capable of doing extraordinary things out of impulse or passion or courage."

Braver noted, "Your women are particularly strong; they take over the books."

"Do you know any weak women, Rita?" Allende replied.

"Not ones I really like!"

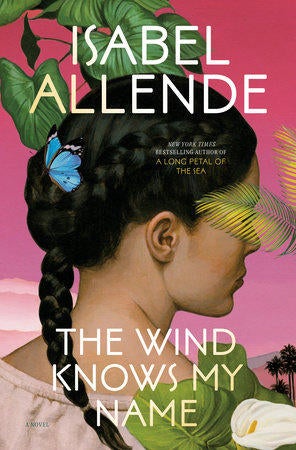

Women and girls play key roles in "The Wind Knows My Name," Allende's latest novel, which draws parallels between Jewish children sent to safety by their families during World War II, and Latin American children separated from parents while trying to cross into the U.S. "The Jewish families had to make the horrible choice of sending their kids alone to save them from the Nazis, not knowing who would receive them on the other side," Allende said. "And when we had this horrible policy of separating the families at the border in 2018, I immediately thought of what those families had gone through then, and how history repeats itself."

Allende's own history is tumultuous. Her father abandoned the family when she was three, and her mother had to return to her parents' home in Santiago, Chile. "She had not been trained to work," Allende said, "because she belonged to a social class and a generation in which women didn't work. She was stuck."

Braver asked, "You didn't want to be like the women you saw around you; you knew that in your heart at a very young age?"

"I wanted to be like my grandfather, who had a car, who had the keys of the house, who had money, who made all the decisions. I wanted to be him," she replied.

"How did the family react to you?"

"I was a lunatic!" Allende laughed. "I was expelled from the nuns at age six, so it wasn't an easy childhood, as you may imagine!"

She married and had two children, but always worked – as a TV personality, journalist, and school administrator.

Braver asked, "Did you ever think, What I really want to do is be a writer?"

"I was afraid to say that," Allende replied. "I never thought that I could. There were no role models. The great writers of Latin America were all male."

Then, in 1973, her world was upended, as the Chilean military seized power from the elected government of her cousin, Salvador Allende. "My country changed in 24 hours," she said. "Try to imagine what it would be if, in the United States, the armed forces attacked the democratic institutions, [and] the president would die in the coup.

"And then I learned that I was on a blacklist. I got out."

She and her family would flee to Venezuela. "I felt very unhappy, very frustrated. I was going to turn 40 very soon. And my grandfather was dying in Chile, and I started a letter for my grandfather to say goodbye."

The letter would turn into Allende's first book, called "The House of the Spirits." Published in 1982, it is a fictionalized account of her own family, Chile's oppressive class system, and the terror of the military coup d'etat. The novel became an international sensation, often called one of the most important books of the 20th century.

"How did the success of 'House of the Spirits' change your life?" asked Braver.

"It gave me a voice when I had no voice,' Allende said. "I realized that this is what I want to do."

Her life would change in other ways, too, as she left her first marriage and Latin America. She has lived in California since 1987. When asked why she moved there, Allende said, "Because I fell in lust with a guy. Came, he was living here, we married, stayed married for 28 years."

But in 2015 Allende's second marriage ended in divorce. She did not think she would fall in love again, yet in 2019, she married attorney Roger Cukras.

And she is comfortable talking about her own sexuality. In her 2021 book, "The Soul of a Woman," she writes: "In candlelight, I might be able to fool a distracted guy who has had three glasses of wine, is not wearing his glasses, and is not intimidated by a woman who takes the initiative."

Is that true? "It is true," Allende said, "and also helps some marijuana. Marijuana blueberries. One blueberry, and you can have wonderful sex. I shouldn't be saying this on camera actually, because I know that Roger's children will listen to this!"

And though she can be lighthearted, Allende is still mourning the death, in 1992, of her daughter, Paula Frias, at age 29 after an attack of porphyria, a hereditary blood disease. "She got the wrong medication, she got severe brain damage, and died a year later," Allende said.

The proceeds from Allende's bestselling book about her daughter, "Paula," helped launch a foundation (now run by Allende's son, Nico, and his wife) that supports groups trying to help young girls at risk around the world. "If you can save a few of those little girls, well, I feel rewarded," she said.

She also continues to feel rewarded by her writing. With no plans to retire, she comes to her office every weekday, where she lights a candle and sits down at the computer, usually thinking and writing in Spanish.

Braver asked, "Is writing still hard for you, or does it just flow?"

"Yeah, the process is always hard, but I know now, which I didn't know before, that if I spend enough time, I will be able to do it."

And as for the impact of Isabel Allende's books on her readers, work that so often deals with injustice and suffering?

Braver asked, "Do you think, when people read your work, that it might bring about change?"

"It can happen," Allende replied. "But I cannot plant those ideas in anybody's head. I don't change people. I just make people realize who they are."

READ AN EXCERPT: "The Wind Knows My Name" by Isabel Allende

For more info:

- "The Wind Knows My Name" by Isabel Allende, translated by Frances Riddle (Ballantine), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Indiebound

- Isabel Allende Foundation

Story produced by John Goodwin. Editor: Remington Korper.