Challenges loom as tech takeover grows

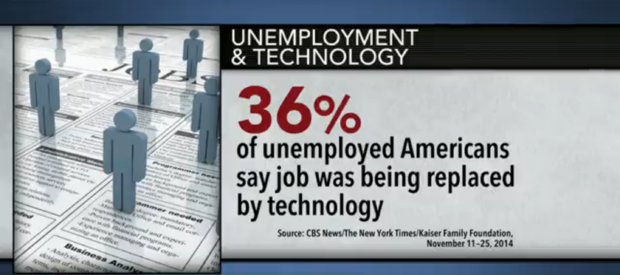

More than 30 percent of unemployed Americans cite technology as the reason they are out of work, and in 2013, Oxford researchers predicted machines could take 47 percent of U.S. jobs over the next 20 years.

In "A World Without Work," Atlantic senior editor Derek Thompson explores the future of American jobs as technology continues to encroach on the workforce.

"This is a piece about taking seriously the possibility that technology replaces enough jobs that it challenges the availability and the psychology of work," Thompson said Wednesday on "CBS This Morning."

- How many companies replace workers with tech?

- Is technology making workers less productive?

- Does technology make people happier?

It's a possibility that is becoming more real every day. Drones may replace the need for delivery workers, contact lenses could revolutionize the health care industry and apps are filling holes for nearly every need.

"In 2005, who would have predicted that cell phones would have threatened hotel jobs? It's a connection nobody would have made, and now Airbnb is the second largest startup in America," Thompson said.

In his piece, Thompson visits Youngstown, Ohio, a once-thriving factory-town-turned-case-study. The technological revolution not only left its mark on the community's economy but also on its psychology.

"Depression, spousal abuse and suicide all became much more prevalent; the caseload of the area's mental-health center tripled within a decade. The city built four prisons in the mid-1990s," Thompson writes.

To some, a world without work represents romanticized relaxation and liberation from stress, but Thompson warned freedom from jobs may not feel so freeing.

"We are somewhat ironically happier complaining about bad jobs than not to be working at all," Thompson said.

That's what psychologists Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Judith LeFevre observed in their 1989 Chicago study. They tasked 78 adult workers to track their positive emotions and anxieties for one week.

"[Csikszentmihalyi] asked people at work, 'Do you wish you were somewhere else?' and asked people at leisure, 'Do you wish you were somewhere else?' Everyone at work said they wished they were somewhere else, and everyone watching TV said, 'No, I'm great right here,'" Thompson said.

But according to their self-reported data, adults at leisure experienced fewer positive emotions and more anxiety than those at work.

"I think that work is more important than money. I think that work isn't just a paycheck. Work is meaning, it's purpose, it's esteem, it's a community," Thompson said. "So what this piece tries to look at is how can we replace some of the structure of work outside of the office if we truly believe some of these jobs are going to go away."

One possible solution to that threat, Thompson said, is "universal basic income."

"This has been a popular idea in U.S. economics and international economics since the 1960s and 1970s," he said. "It essentially says that everybody gets a certain amount of money every single month from the government."