At Stanford, Romney got his bearings in a year of change

(CBS News) PALO ALTO, Calif. -- Mitt Romney was on his own for the first time in his life when he arrived at Stanford University in the late summer of 1965.

Though 2,000 miles from his Michigan home, he wasn't far outside his comfort zone --not at first, at least.

An affable, good-looking and intellectually curious young man on a campus where many students matched that description, Romney began making friends on his very first day at Stanford.

Arriving on campus a day before the dorms opened to new students, Romney spent that first night at an administrator's house where he met a classmate, Paul Richardson, who would become a close companion.

"I remember late that night he talked about his opinion on the economy, and he could talk seriously about the Taft Hartley Act -- he was very aware of the features of it," Richardson recalled. "He had a very energizing personality. I admired him tremendously."

As a fun-loving kid who in high school had a penchant for crowd-pleasing gags, Romney would have taken note of the "Freshman's Pocket Guide to Stanford Life," which informed members of the incoming class that a "bitchin' R.F." was the colloquial term Stanford students used to describe a particularly well-played practical joke.

As the class of '69 poured into Palo Alto from around the country, there was excitement in the air over rumors that the university was on the verge of relaxing its stringent liquor policies. But as a non-drinker, Romney didn't much care about that, nor was he overly concerned about potential run-ins with "Captain Midnight" -- the pejorative term that students assigned to the campus police.

Aside from participating in the annual high jinks surrounding the big football game with cross-bay rival UC-Berkeley, Romney avoided any hints of trouble that fall.

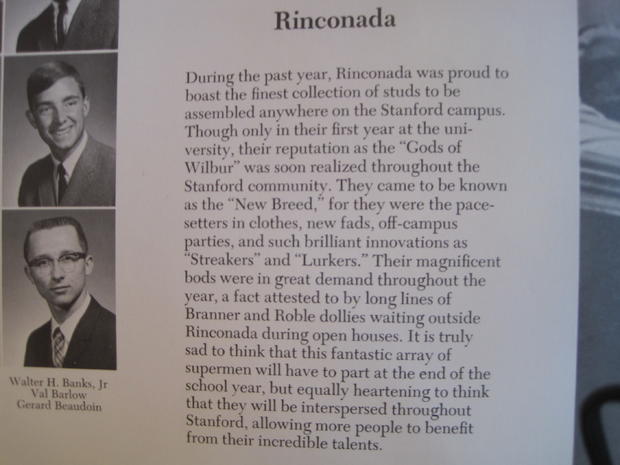

Though his tight-knit Rinconada Hall dorm mates would later wax poetic in the class yearbook about their "magnificent bods," which were allegedly "in great demand throughout the year," Romney only had eyes for his sweetheart, Ann, about whom he spoke incessantly.

From the third-floor room that he shared with Mark Marquess, a scholarship athlete who has coached Stanford's top-flight baseball team for the last 36 years, Romney did not have a clear vantage point on the sharp needle of change that was about to suddenly pop his campus bubble.

Change and Tradition

In the fall of 1965, the Bay Area was Ground Zero for a political and cultural upheaval that would soon explode nationwide and define the latter half of the decade for Romney's generation.

At a Palo Alto coffee house just down the street from Stanford, three young musicians had formed a jug band the previous year and were achieving some local popularity as a rock-and-roll outfit known as The Warlocks when Romney arrived in town. In December, the band members decided to change their name and gave their first performance in nearby San Jose as The Grateful Dead.

As Romney and his classmates attended school dances and pep rallies, Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters -- whose idea of a practical joke (dosing an unsuspecting recipient's drink with LSD) was rather different than Romney's -- were posting signs around Palo Alto to solicit new recruits for their "Acid Tests."

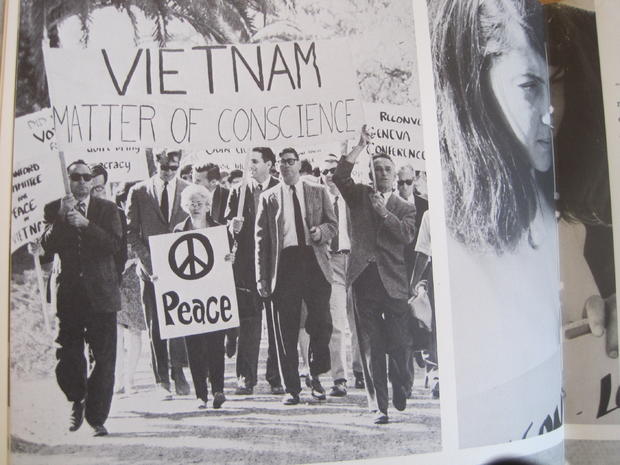

In late January, the resumption of U.S. airstrikes in North Vietnam brought with it a surge of student anti-war activity at Stanford, where a small core of radical students was starting to catch up with their Berkeley cousins in visibility and temerity, if not in numbers.

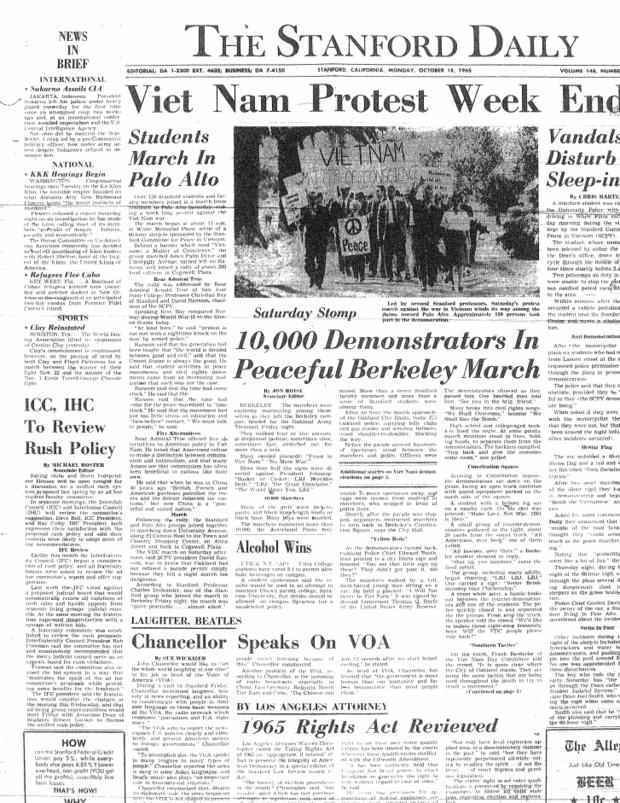

Over the course of the academic year, The Stanford Daily had documented with increasing regularity the anti-Vietnam demonstrations that were picking up steam in the region, particularly in Berkeley, where at one protest march, it was reported that "many of the girls wore jackets, pants, and black knee-length boots or black hose. Many boys were bearded."

Facial hair may have remained something of a novelty at Stanford, but sartorial norms were changing there, too.

Stanford ROTC students were being told by their superiors that they should change into civilian clothes immediately after completing their drills in order to avoid ridicule, and many of Romney's classmates were growing their hair in the bushy style of The Beatles, who visited San Francisco's Cow Palace in August.

Vietnam became the dominant political topic on campus, as students worried about whether the deferrals that their local draft boards had granted them would last as the demand for fresh inductees grew precipitously.

Meanwhile, Romney focused on integrating the traditions with which he was raised into his new life at Stanford.

As an active member of the Latter-day Saints student group, Romney met regularly with his fellow unmarried Mormon students at the church on Valparaiso Avenue in Palo Alto, where he also attended Sunday services.

His regular church attendance was unusual among his dorm mates, but his faithfulness did not interfere with his friendships with non-Mormon friends.

When he was among his religious cohorts, there were dances on Tuesday nights and three hours of services on Sundays led by Bishop Henry Eyring, who counseled Romney and his peers. (Eyring currently serves as the first counselor in the first presidency in Salt Lake City -- the second highest-ranking position in the Mormon Church.)

In March of 1966, Romney turned 19 and became eligible to serve the 30-month mission abroad that Mormonism strongly encouraged its young men to complete.

But if Romney was already planning to leave Stanford after his first year there, he didn't broadcast that information to the brothers of the Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity house.

Stanford freshmen were not permitted to rush fraternities until spring semester and could not become full-fledged members until their sophomore year.

In deciding to rush Phi Kappa Sigma, Romney chose a house that was known for hosting an eclectic mix of social, good-natured, and popular kids who liked to party but were also serious about academics.

Though Phi Kappa Sigma had some jocks in the house, the membership on the whole was not a stereotype of one thing or another and was known for its welcoming nature.

When Romney rushed that spring, he had only to endure the rituals of "Help Week" -- Phi Kappa Sigma's benign take on Hell Week, the unpleasant rite of passage at other fraternities.

"In our unbiased view, we were the best fraternity on campus -- a view shared by many women on campus, which was, of course, equally important," said Gil Berkeley, a junior-year Phi Kappa Sigma brother in the spring of '66. "We were known as the nice guys. We treated women with respect, we had a reasonably diverse membership, and we were good students."

The fraternity's membership may only have been "reasonably" diverse, but it was diverse enough to draw attention at a time when such groups were typically segregated by race.

The previous year, Stanford's Phi Kappa Sigma house had accepted two black students and became the first chapter of the national fraternity to have any minorities within its ranks, according to former members. When he decided to rush, Romney would have been well aware of that reputation for inclusiveness.

According to Bob Waterman, a junior-year fraternity brother when Romney rushed, the chapter's acceptance of minority students had made it a "fraternity non grata" in the eyes of the national organization, and the Stanford house was later dissolved sometime in the 1970s.

In separate interviews, three Phi Kappa Sigma members recalled that Romney accepted an offer to join the fraternity. They also recalled being surprised when he ended up leaving for his mission in France that summer and transferring to BYU upon his return 2 1/2 years later.

"Had we known that he wasn't coming back, I think we would've said no; we were very oversubscribed, and we had people sleeping in the attic," Waterman said. "I would assume that his decision not to come back happened after his freshman year."

Though he did not become a full-fledged Phi Kappa Sigma brother, Romney did receive at least one tangible benefit from the connections that he gained from rushing the fraternity, according to John Ashton, who was a senior in the house.

Though Romney drew disbelieving ridicule in some quarters for his 2007 recollection of having hunted as a youth for "small varmints," Ashton said that Romney did enjoy handling a gun while at Stanford.

A firearm had not been among the possessions Romney brought with him to college, and so one day that spring he came to Ashton for assistance.

"At that time, if you were under 21, you had to have a 'responsible person' who was in California sign [a document] taking responsibility for the ownership of a pistol that he was wanting to buy," Ashton recalled. "So I signed it knowing full well they wouldn't come after me -- they would come after [Romney's father] George if there were any problems!"

Ashton, who is a lawyer in Salt Lake City and has crossed paths with Romney several times since their college days, said he was surprised when the presumptive Republican presidential nominee did not recall his act of fraternal guardianship decades later.

Taking a Stand on Vietnam

As Romney was forming bonds with his would-be frat brothers, the war in Vietnam hit home emphatically as his freshman year neared its end.

Romney's Michigan-based draft board had already granted him one academic deferment the previous spring as a high school student. In October, he received a second student deferment.

Meanwhile, Romney discussed his support for the war with his likeminded friends.

"We were strongly in favor of military effort being made, based on what we knew at that time," Paul Richardson recalled.

Up until that time, the 2-S college student deferment was considered relatively iron-clad by most who received it, but with the need for more U.S. troops to wage an escalating war, a sense of uncertainty was settling in among Romney's male classmates.

On March 28, The Stanford Daily ran a front-page story under a headline intended to catch the eye of Romney and his classmates: "All Men Urged to Register for Selective Service Test."

The story explained that the Selective Service -- the government agency that managed the draft -- would be on campus on March 14 and 21 to administer a voluntary test that local draft boards could use to make decisions about the status of individual students' deferments.

The methods by which draft boards would consider the results were subjective and secretive, but the test was widely seen as an opportunity for Stanford students to increase the chances of keeping their deferments for the foreseeable future.

A student with even mediocre grades at such an academically rigorous institution, the thinking went, could offset that middling transcript by scoring well above the national average on the standardized test and thus be more likely to stay out of the draft for as long as he remained in school.

"The Selective Service test used in 1951 was designed so that a score of 70 was equal to the average score made by college freshmen who took a well-known scholastic aptitude test, and students scoring above that were recommended for deferments," John Black, the director of Stanford's Counseling and Testing Center, explained in the Stanford Daily article. "If some local boards pay limited attention to the test, they can hardly fail to be impressed by very superior scores."

As the date of the Stanford draft tests approached, a shaggy-haired, mustachioed student named David Harris launched what was widely perceived to be a quixotic campaign for student body president.

Harris was a well-known radical who had been to Mississippi as a civil rights worker and looked the part in his faded Levis, moccasins, and rimless glasses.

As the "sponsor" for the third floor of Rinconada, Harris also happened to be Mitt Romney's resident adviser, though the son of the famous politician did not impress Harris.

"It's not like George Romney was George Harrison," Harris said. "OK, his dad's a cheese . . . he made no ripple on me."

Harris' campaign began as something of a lark. "I didn't even try to win the damn thing," he recalled.

At one rally, the candidate recruited a student-led band to warm up the crowd. Lacking an adequate sound system for the event, Harris turned to a classmate who happened to be the younger brother of the lead guitarist for the Jefferson Airplane. The psychedelic rockers, who were on the verge of achieving mainstream success, agreed to let Harris borrow their equipment in exchange for an ounce of pot.

No one was more surprised than Harris in late April when he won easily in what was the largest turnout in the history of Stanford student government elections. Harris made national news for the feat, and his landslide victory was emblematic of the extent to which the university's climate had changed in the months since Romney first arrived on campus.

A couple of weeks later, a student-led group called the Stanford Committee for Peace in Vietnam (SCPV) raised its first public objection to university officials over their cooperation with the Selective Service by offering the draft tests at the university.

"There was this very big issue on campus about the decision-making process and how students were just totally cut out of that," said Nelson Bonner, who was a sophomore and active in Stanford's growing anti-war community. "The feeling was that not only do we not like the draft test itself, but we don't like the way it was foisted upon us and want some say on how decisions get made in the future."

When about 2,500 students took the test when it was first offered on May 14, SCPV members were on hand to pass out their own "Vietnam Exam," which challenged commonly held assumptions about the war.

The following week, the SCPV sent a letter to Stanford University President Wallace Sterling to demand that the university withhold information on students' academic rankings from the Selective Service, cancel the second draft test (scheduled to take place the following Saturday), and provide information to students on possible legal steps to avoid being drafted.

Sterling said that he would discuss the students' demands with them privately, but the activists were in no mood to dally.

While Sterling was at a meeting in San Francisco on May 19, the SCPV held a rally on White Plaza -- the campus' "free speech" area -- and then led a march of about 100 students to Building 10, which housed the university president's office.

With no one there to block them, the demonstrators soon moved into the lobby and hallways outside Sterling's office.

Many of them soon disbursed, but a group of about 40 settled in for a night on the chairs, couches and floor, displaying placards with such slogans as "I am just expendable" and "Uncle Sam needs cannon fodder."

As the student occupiers passed the night by doing homework, chatting quietly with one another, and singing folk songs, Sterling's secretary appealed in vain to their sense of shame and denounced their actions as "darned tom-foolery" to a student reporter who was covering the event.

Many of the students who took part in the demonstration emphasize that while taking the draft test would have helped them avoid the draft, they protested for the benefit of their peers who did not have an expensive and exclusive education to save them from their fate in Southeast Asian rice paddies.

"We weren't doing it to protect our privileges," recalled Art Eisenhon, a graduate student who took part. "We thought the draft was an abomination."

As the few dozen protesters remained encamped, hundreds of other students paid $2 for a ticket to enter Tresidder Union Deck and catch a glimpse of an up-and-coming pop band called The Lovin' Spoonful, which played an outdoor set that night.

The next morning, Mitt Romney woke in Rinconada and donned a crisp pair of light pants, a white button-up shirt, and a dark blazer.

By about 9 a.m., the crowd of anti-Vietnam demonstrators in Sterling's office suite had swelled again. They were now met by a group of about 75 counter-protesters, who carried signs reading "Support President Sterling" and "Down with Mob Rule."

The leader of the counter-protesters, Carey Coulter, recalled in a January interview with Buzzfeed.com that Romney happened upon the scene and offered to help handle the growing contingent of reporters and news photographers.

A photographer captured a picture of a visibly cheerful Romney standing among his fellow counter-demonstrators and holding a sign that read "Speak out. Don't sit in."

Romney and his cohorts engaged their fellow students in sporadic arguments into the afternoon, as some officers in the "Captain Midnight" contingent moved in to ensure the peace was kept.

As the hours ticked away, some of the remaining students inside Sterling's suite engaged in a new kind of protest that they called a "love-in." They passed candy and sodas through the guarded door to those outside and rained flowers upon officers and counter-demonstrators who were still on hand.

Some of the counter-demonstrators amused themselves by addressing the bearded anti-war protesters individually as "Moses" and "Jesus."

The scene bore little resemblance to the much larger and combustible anti-Vietnam protests that would blanket Stanford and campuses across the country in the coming years.

One campus police officer captured the relatively placid mood when he told a Stanford Daily reporter, "I'm not mad at anybody. I wish I were in Jig's Tavern or trout fishing."

A smaller group of SCPV members remained in Sterling's suite for a second night, and about 800 students took the second scheduled draft test on Saturday morning without incident. The Romney campaign did not respond to questions about whether Romney took the draft test himself.

The last remaining 27 student protesters ended the 50-hour sit-in on Saturday afternoon by exiting the building with their demands unmet but confident that they had made their point.

On Sunday, Miles Davis became the latest musical act to visit campus, as Romney and his fellow students turned their attention to final exams.

A Complicated Legacy

Many of the students who took part in at president's office sit-in have wondered as Romney's name filtered into the news over the years whether his worldview might have been affected had he remained at Stanford and experienced the coming countercultural heyday, a period when anti-Vietnam protesters would become a clear majority.

David Harris, who served over a year in federal prison for draft evasion and was for a time married to famed folk singer and activist Joan Baez, regards as telling Romney's decision to speak out against the anti-war students at the dawn of a changing era.

"He missed out on the great issue and adventure of his time," Harris said. "He was right there when it took off. He could've come to Stanford and gone native, you know? But he didn't do that, and that tells you something right there because lots of people [from conservative backgrounds] were doing that."

Romney's freshman-year classmate Mike Roake brought Romney to his home in nearby Hillsborough a few times during the academic year they spent together at Stanford.

Though he stressed in an interview that his political views remain "180 degrees" opposed to Romney's, Roake nonetheless recalled his former classmate fondly. In Roake's view, Romney's spring semester Stanford experience was the only time in the Republican's young life when he found himself outside of his comfortable boundaries.

"He went on his mission, which was its own bubble, and then to BYU, which is a bubble, and then to married student housing at Harvard," Roake said. "There was a sea change [at Stanford], and he was not influenced by it."

Roake, who was in the Naval ROTC at Stanford, went on to become a medevac pilot in Vietnam.

As it was with many members of his generation, Romney's personal relationship with Vietnam was a complicated one.

In July of 1966, the same month he left for France to serve his mission, the Selective Service granted Romney a 4-D categorization as a "minister of religion or divinity student."

This deferment status was controversial at the time, as critics argued that it allowed young Mormon men to avoid the draft disproportionately.

The practice of granting 4-D deferments to Mormons for the purpose of serving their missions sparked a federal lawsuit by non-Mormons in Utah, and the LDS Church eventually cut down on the number of missionaries it permitted to receive 4-D status.

Upon his return to the United States and subsequent transfer to BYU, Romney received two more student deferments before being declared available for military service on December 1, 1970. The high number he drew in the 1970 draft lottery (300) ensured that he would never be compelled to serve in the military.

In a May of 1970 Boston Globe story, Romney was quoted echoing the comment suggesting a dramatically altered view of the war that all but ended his father's presidential campaign before it had officially begun. "I think we were brainwashed," the 23-year-old Romney said. "If it wasn't a political blunder to move into Vietnam, I don't know what is."

Despite his own public criticism of the war while it was still raging in 1970, during his 1994 Senate campaign Romney criticized Democratic opponent Ted Kennedy for speaking out against Vietnam at the time.

"I was disturbed even then of his criticism of the effort there at a time when we had men and women on the ground in Vietnam," Romney said in an interview with The Boston Globe. "There are times to be critical, but once we have lives at risk, we stand behind the commander in chief."

As far as his own lack of service in the military, Romney told The Boston Herald in 1994: "It was not my desire to go off and serve in Vietnam, but nor did I take any actions to remove myself from the pool of young men who were eligible for the draft."

Romney's recollection appeared to change while running for president 13 years later when he told the Globe that while serving his mission in France, he had "longed in many respects to actually be in Vietnam" and that it was "frustrating not to feel like I was there as part of the troops that were fighting."

No matter what his true thinking was about putting his life on the line for his country, Romney's year at Stanford marked a critical transition in his life.

When he became an active participant in the defining debate of his generation, Romney set himself apart from the vast majority of students on campus who identified with neither the anti-Vietnam demonstrators nor the counter-protesters in those relatively early days of the war.

As the son of a nationally prominent politician, Romney knew that his public stand would draw particular scrutiny and deprive him of the relatively anonymity he had enjoyed at Rinconada Hall and among his church friends and prospective fraternity brothers, but he did it anyway.

When Romney left Palo Alto behind that summer, gone forever was an innocent youth that had been defined by fun and frivolities. In its place emerged an earnest young man who had asserted himself when challenged and found strength in committing to his deep-seated principles.

This story was reported by Scott Conroy and CBS News' Laura Strickler and written by Conroy.