Facial reconstructions help identify murder victims

NEW YORK -- In April of 2001, the skeletal remains of a man were discovered by New York City parks employees clearing brush near Brookville Boulevard in Queens. The man, who authorities estimated was between 18-28 years old, had wavy brown hair, and was found wearing Calvin Klein jeans and a yellow metal earring.

He had been shot multiple times in the head.

When graduate student Richard Comstock unpacked a replica of the victim's skull for his forensic sculpture class at the New York Academy of Art in January, that's all he knew. In fact, it was nearly all anyone knew about the nameless man- DNA hadn't turned up a match in national databases, there was no one to compare dental records against, and the skeletonized state of the remains rendered fingerprinting impossible.

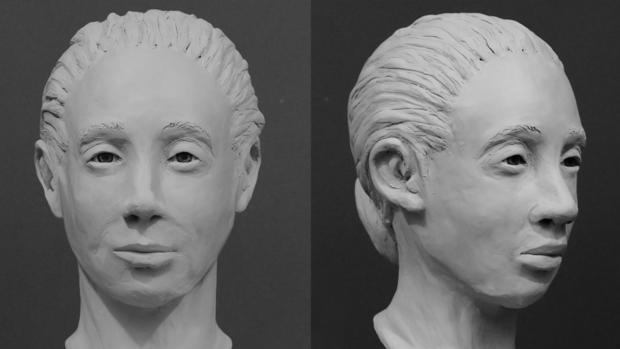

The victim was among some of the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner's most challenging unidentified remains cases, officials there say. Now, however, Comstock and his classmates are hoping to revive the identification efforts - by giving unnamed victims their faces back. Jan. 12 through 16, a class there worked under the guidance of a forensic artist from the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), sculpting facial reconstructions of 11 victims in the hopes that someone will recognize them.

"It made it a little more personal to see such a gruesome murder - it made it a little more real," Comstock said of learning how his victim died. "Obviously you wonder what happened."

Many of the reconstruction cases the students worked on were of victims whose remains were skeletal, meaning their faces weren't viewable. Some had been victims of homicide - though for others, a cause of death wasn't clear. For many, identification methods like DNA, dental record comparison or fingerprinting hadn't worked or wasn't feasible.

"We had really kind of exhausted all of the traditional means or methods of identification, which is why facial reconstruction - which some would say is a non-traditional method - could be a way to get some attention to a case," said Brad Adams, the director of the forensic anthropology department at the medical examiner's office.

Comstock said he hopes to use his artistic abilities to help his victim's family find answers about what happened to their loved one - exactly what class instructor and forensic imaging specialist Joe Mullins has been doing for the past 15 years at NCMEC.

Mullins is one of four full time forensic artists at NCMEC, specializing in sculpting facial reconstructions from skeletal remains. He's worked on hundreds of skull reconstructions and thousands of age-progression images for long-missing children, including high profile cases such as that of Jaycee Dugard, the California girl abducted at 11 who was found alive after more than 18 years.

In each case, he's hoping that his work will jog someone's memory and prompt them to pick up the phone.

"As a forensic artist, I live in a wonderful world where "almost" is good enough," Mullins said. "If somebody sees an image that kind of looks like someone they haven't seen in a long time and it sparks that recognition, we've done our job successfully."

One major challenge in Mullins' line of work is the sheer number of unidentified victims on medical examiners' shelves and the relatively small number of forensic artists that have the skill to take on a 3-D facial reconstruction. Across the country, more than 10,000 unidentified cases remain active in the National Missing and Unidentified Persons (NAMUS) system, a national database that tracks missing people and unidentified bodies.

Each year, about 4,400 unidentified remains are discovered in the U.S. and entered into the system by medical examiners and coroners. More than 1,000 of the cases remain unidentified after one year, according to NAMUS.

About eight years ago, Mullins got the idea to enlist students in the identification effort after working on several reconstructions with the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner and seeing the problem first-hand. But there was one big hurdle.

"I've always had the reservation about having to release the actual remains out of my custody," Adams said.

Releasing the skulls to students could be problematic, but having a class take on "real" cases did have its merits - it would be an opportunity to get several of the time-consuming projects done at the same time, Adams said.

It took a few years for technology to catch up with their vision. A little more than a year ago, the medical examiner's office obtained a 3-D printer through a grant from the National Institute of Justice. With it, Adams was able to 3-D print realistic replicas of the skulls of unnamed victims.

It was the perfect solution - Adam's office was able to maintain custody of the skulls, while the students could work with a replica to re-create the faces of real victims. And, Adams said, adding any kind of visual to a text-only description in a media report or a database could be crucial in uncovering an identity.

"I can tell you it's a 17-to-25-year-old white female, and that's going to narrow down the pool of individuals," Adams said. "But if we can put a face to that, it's one more bit of information that may jog someone's memory - it might draw somebody in, even if it's just enough to have someone take another look."

The New York Academy of Art was an ideal fit for the project because of the students' knowledge of anatomy and skill with sculpture, said the school's continuing education director John Volk. The Manhattan graduate school, which focuses on intensive technical training in fine arts, launched the forensic sculpture class as a way for its students to marry art with forensic science, and invited Mullins to lead the workshop.

"Our students were told right away when they came in that they were not allowed to use their artistic license with this project at all - they had to simply work with the genetics that came from the skulls themselves to make a reconstruction of what the person looked like," Volk said.

Students used averages to determine tissue depth in some portions of the facial reconstruction, but they also let the skull itself direct their work for facial aspects like placement of the cheekbone and angle of the nose, Volk said.

General demographic information like age, sex and race also played a role. But students had only a few basic descriptors to work with - for the rest, they needed to let the skull speak to them.

"I felt like her skull was telling me what to do, telling me where to add the clay, telling me how to form her face," said graduate student Stefania Panepinto of her victim, a young woman found dead in a New York field in 1983.

Two of the eleven victims given the class, including Panepinto's, have recently been identified, Adams said - not through the facial reconstruction project, but through DNA. His office isn't releasing the two identities because it's still early in the notification process for their families, he said.

At first, Volk said, it was a bit eerie for the students as they unpacked the skull replicas. But about four days into the class, something changed. Students were no longer looking at a skull - a relatively abstract concept of a human - but at a person.

"You're just kind of looking at it, and it's looking right back at you - it's an amazing thing," Comstock said.

Volk said the students began to feel a strong connection to their victims - and a strong sense of responsibility to help them get their names back.

"As their faces started to emerge, I really felt like I was resurrecting lost souls," Panepinto said.

Mullins knows the feeling well. Working alongside the class, he re-created the youngest victim - a child found shot in the head in a Vermont field next to a woman and another child in 1935.

Mullins is hoping not only to identify the victims, but to encourage students like Panepinto and Comstock to pursue forensic art professionally.

"Technically they're already professional forensic artists - they've got one under their belts," Mullins said. "But there's thousands and thousands of skulls out there - for all of them who have the forensic art bug and want to go out there and do more, there's plenty of work."

Eventually, Mullins hopes to replicate the forensic sculpture class at other schools nationally, working with unidentified cases from medical examiners' offices in other jurisdictions.

Some of the New York Academy of Art students have expressed an interest in pursuing the career professionally, Volk said. But for now, they're feeling hopeful that their work just might lead to an identification.

"They want to bring a name to that person - they want to have some closure for the families of those people," Volk said. "They'd like to have that person's story told."

If you recognize any of these victims, please call the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner at 212-323-1201.