Are robots or Mexicans to blame for U.S. job losses?

The vanishing of those fabled factory jobs that once lifted so many blue-collar Americans into the middle class is a tragedy. President Donald Trump rode malaise over this sorry situation to victory -- and he has put the issue front and center by pledging to turn U.S. manufacturing’s fortunes around.

To do so, his administration will need to answer the central question regarding the decline of manufacturing: What is primarily to blame for fading factory employment? Is it mostly the siren song of inexpensive labor that enticed American companies to ship jobs to countries like China and Mexico, and American consumers to buy cheaper foreign imports? Or is the bigger culprit automation, which has been replacing human hands with technology at least since the Industrial Revolution, and even before?

The answer is important because it will help shape how -- or if -- the U.S. government and corporate America can remedy the job-loss quandary. The truth is that both automation and offshoring are powerful, and perhaps even equal, factors.

“It would be naïve to attribute it all to technology,” said economist Hugh Johnson, who runs his eponymous investment firm in Albany, New York.

The question has a political dimension. Some have partisan reasons to say either offshoring or technology is predominantly to blame. For Mr. Trump, focusing on the impact of offshoring gives him a dragon to slay, thus pleasing his base. On Monday, the White House released a compilation of his achievements in his first month, including: “President Trump has successfully coordinated with several companies to bring thousands of jobs back to America.”

For Democrats, Never-Trumpers and other critics of the president, putting the onus on automation is a bid to make his crusade seem like a foolish and misguided effort to resist inexorable forces like innovation and globalization.

Pinning the blame for the disappearance of manufacturing jobs on offshoring is perhaps more emotionally potent. With dark foreboding, Mr. Trump points to the flight of factory jobs to low-wage regions of the globe as nothing less than an existential threat to the working class. In his inaugural address, he spoke of “rusted out factories scattered like tombstones across the landscape of our nation.”

Underlining that theme, Mr. Trump has publicly sought to shame individual American companies that are sending work abroad and laying off domestic employees. He takes credit for convincing United Technologies (UTX) to scrap plans for shutting an Indiana plant, where its Carrier subsidiary makes furnaces, and transferring the work to Mexico. “The Trump administration is now putting a new twist in the mix to say: build here what you sell here,” said John Augustine, chief investment officer of Huntington National Bank.

Whether Mr. Trump’s finger-pointing tactics will ultimately do much to preserve American jobs is open for debate -- even the president can’t police the decisions of hundreds, if not thousands, of companies. In December, when he lauded wireless provider Sprint’s move to bring 5,000 jobs back to the U.S., that constituted just a fraction of U.S. employment gains. By comparison, the economy added 6,000 jobs per day in 2016.

Plus, a chunk of the lost jobs -- although it’s unclear how many -- were indirectly offshored. That is, the job losses were not a direct result of U.S. companies moving them abroad. Rather, American consumers -- who account for roughly 70 percent of ecoomic activity here at home -- opted for less-expensive imports, crowding out any number of domestically produced goods. Few American textile and furniture makers closed their shops and transferred operations to Asia. They simply went out of business, and Asian competitors filled the remaining vacuum.

That said, one way the president could make a big difference is by persuading Congress to grant him far more potent weapons, such as tax penalties for offshoring and stiff tariffs on imports, in particular on American companies’ foreign-made goods sold in the U.S. Such policy shifts could also have considerable downsides, it’s worth noting. Skeptics warn such policies could harm corporate performance by boosting payroll costs, hurt domestic consumers by making imports more costly and touch off a disastrous trade war.

Meanwhile, those who blame automation for job losses have a tough time prescribing an antidote. In fact, their perspective invites a fatalistic attitude, in the eyes of Adams Nager, economic policy analyst at the Information Technology & Innovation Foundation (ITIF). As he wrote in a recent report, automation-induced job reductions mean to some that “there is nothing that can be done to bring them back.”

At times, fighting the shrinkage of industrial jobs does appear like King Canute’s hopeless attempt to command the tide to recede. When United Technologies seemed to knuckle under to Mr. Trump, it nevertheless said it will still ship some jobs to Mexico and plans to automate more of its Indiana operations.

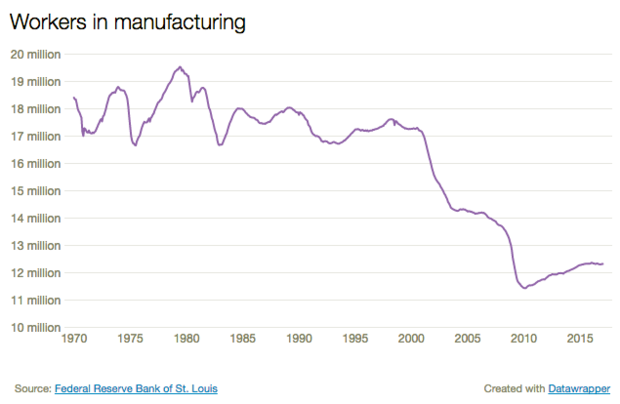

Manufacturing employment got walloped in the Great Recession, falling from 13.7 million in December 2007, when the economic downturn began, to its January 2010 low point of 11.4 million. Since then, less than half of those lost factory positions have been regained, with last month’s level reaching only 12.3 million.

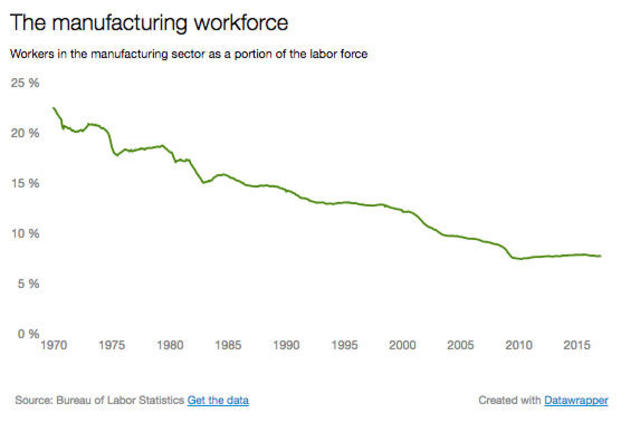

But the decline of manufacturing jobs is a longer-term problem that predates the recent recession: From 19 million in 1980, they gradually lost ground over the next two decades, and really plummeted starting in 2000, from 17.3 million, by almost a third, to today’s level.

Here are the cases for each, automation or offshoring, as the primary driver of factory employment’s dark days, and also a look ahead to a possible outcome:

Automation. Famously, or infamously, depending on your viewpoint, fast-food executive Andrew Puzder in an interview last spring perfectly summed up the attraction for employers of automation. Machines, said Puzder, who Mr. Trump had nominated to serve as his labor secretary, “never take vacations, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex or race discrimination case.”

While that comment may seem cold-hearted -- the controversial Puzder last week withdrew from consideration for the Cabinet post amid strong opposition in the Senate -- it carries an undeniable economic logic.

Undoubtedly, automation has played a potent role in the decline of the U.S. manufacturing work force. In 2012, the J.M. Smucker (SJM) jam plant in Orrville, Ohio, for instance, replaced a 60-year-old factory with a new one, which does the same work with a third fewer people.

Consider oil and gas drilling employment, which was slashed when petroleum prices fell to $26 per barrel early last year from $120 in 2014. Some 150,000 oil workers lost their jobs in the U.S., about a third of the total, according to calculations by industry consultant Graves & Co. Now, with crude fetching $53 a barrel, production is ramping up again, and so is oilfield employment, but just marginally.

A report in the New York Times indicates that only about a third of the headcount will be restored, and many of them have tech training. That’s because of newly automated production, like an automatic water pumping station for use in “fracking,” which replaces hundreds of water truck trips to a drill site.

To economist Johnson, the plight of factory employment is evolutionary, and has a parallel in the history of American farming. “In the early 20th century,” he said, “there was a shift from an agriculture-intensive economy to an industrial economy driven in part by the introduction of technology to farm production -- the tractor, the reaper.” In 1850, farm workers composed 62 percent of the labor force -- by 1950, it was 12 percent. Now, by the American Farm Bureau’s count, the figure is 2 percent, and those folks produce 262 percent more food than in 1950.

Michael Hicks, an economist at Ball State University, calculates that 88 percent of manufacturing job losses in recent years were due to productivity enhancements -- robots to run assembly lines and information technology to track inventory and the like, tasks that rank-and-file workers used to perform.

But not all economists concur that it is that high, and note that reliable polling and in-depth plant-by-plant data are hard to come by. “We have no real hard numbers to lean on,” Johnson said.

When the agriculture-to-industrial shift took place, farm workers simply migrated to cities to work in factories. Nowadays, the trend toward tech makes a similar transition harder. Not every assembly line worker can become fluent in computer code.

Offshoring. As President Trump constantly points out, the U.S. has steadily bled manufacturing jobs to cheaper-paying locales for years. While some dismiss his alarms as anecdotal, the tally is undeniable. The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation estimates that two-thirds of the 5.7 million factory jobs lost between 2000 and 2010 were the result of foreign trade.

The pay differential between the U.S. and less-developed nations is sobering. In 2015, manufacturing hourly costs, which include taxes, was $37.71 in the U.S. and a mere $5.90 in Mexico, according to the Conference Board. To be sure, Chinese wage gains in recent years have brought them much closer to the U.S. level: Some studies put China’s average manufacturing pay at only 4 percent behind America’s. Other Asian nations, however, remain much cheaper. The Philippines is $2.16, for instance.

The trajectory of U.S. industrial job losses is telling, by the reckoning of Dean Baker, co-director at the Center for Economic Policy Research. He notes that job losses accelerated from 2000 to 2007, when the trade deficit shot up to 6 percent of gross domestic product (it has fallen to 2 percent since). In other words, the U.S. had a surge of imports.

“The people in the states hit the hardest like Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania are absolutely right to believe that trade has hurt them, their friends and communities,” he wrote.

To the ITIF’s Nager, ebbing U.S. productivity growth and foreign mercantilism have eroded U.S. competitiveness on the trade scene. Mercantilism means that trade partners like China restrict the entry of others’ goods and boost their own by artificially holding down their currency’s value, making their wares less expensive in the U.S.

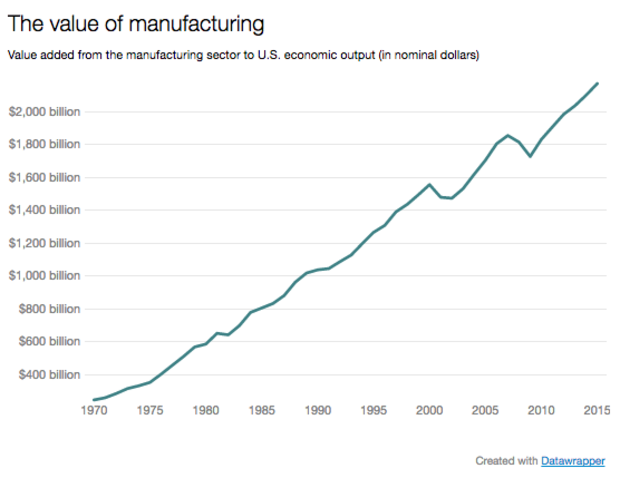

Why the situation might get better. Returning to the glory days of America as the world’s untouchable industrial titan is a stretch. But incremental improvement is conceivable. The fact remains that the U.S. is more productive than anyone else.

As Oxford Economics points out, U.S. factories are 90 percent more productive than Chinese facilities, with technology providing much of the American edge. For 2016, measuring factors that ranged from workers’ talent to supply chain efficiency, consulting firm Deloitte ranked U.S. manufacturing No. 2 behind China,

At the same time, a small yet noticeable counter-trend is under way: reshoring, where U.S. employers have brought back jobs they sent abroad. An advocacy group called the Reshoring Initiative says 265,000 jobs have returned to American shores from 2010 through mid-2016. Reasons: rising wages in some other countries, shorter delivery times at home and a greater ability to meet changing customer demands.

So for unemployed industrial workers, maybe some hope flickers.