100.4 degree Arctic temperature record confirmed as study suggests Earth is warmest in at least 12,000 years

Less than two weeks ago, the small Siberian town of Verkhoyansk soared to 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit, appearing to break an all-time record for the Arctic and alarming meteorologists worldwide. Now that temperature record has been verified by Russia's state weather authority.

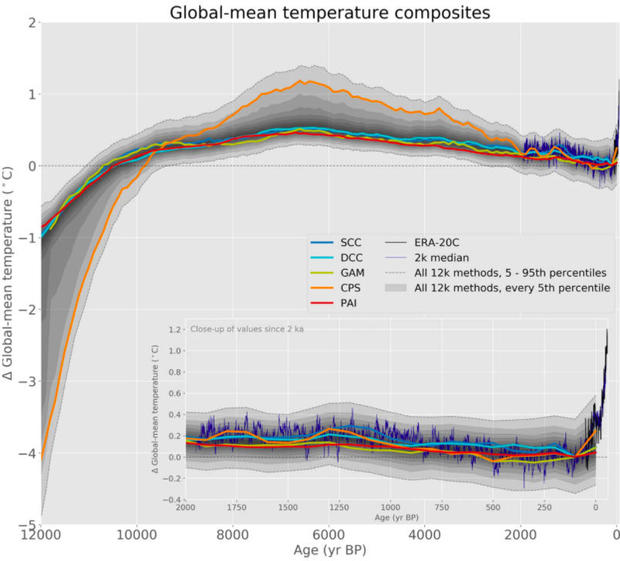

The confirmation came the same day a comprehensive new study was released suggesting that present-day global temperatures are the warmest they have been in at least 12,000 years, and possibly far longer. The study used a variety of geological clues and statistical analysis methods to reconstruct ancient temperature estimates.

In a press conference Tuesday, the head of science at Russia's Hydrometeorological Centre confirmed that the town of Verkhoyansk did indeed reach 100.4° F on June 20th. The official confirmation was requested by the World Meteorological Organization.

Writing on Twitter, the Russian state weather authority said: "In Verkhoyansk from June 18 to June 28, 2020, the maximum temperature exceeded 86° F… with a peak on June 20 to 100.4°. June-2020 in Verkhoyansk...became the warmest in history."

Ten days after that record was set, the heat wave still persists. On Tuesday, a town in the Sakha Republic, 450 miles north-northwest of Verkhoyansk, and also 450 miles north of the Arctic Circle steps from the Arctic Ocean's Laptev Sea, hit an astonishing 93 degrees Fahrenheit. That's 40 to 45 degrees above normal.

The record heat in parts of Siberia during the month of May was so remarkable that it reached five standard deviations from normal. In other words, if hypothetically you were able to live in that area for 100,000 years, statistically speaking you should only experience such an extreme period of temperatures one time. Climate change has now increased that chance.

Zack Labe, a postdoc in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University and an expert on Arctic climate, told CBS News that while he is concerned by the recent heat, he is more unnerved by its staying power. "I am still much more alarmed by the persistence of the record warmth — since December 2019, western Siberia temperatures have averaged nearly 9°F above average (1981-2010), which is quite astounding."

The extended Siberian heat wave is due to an usually persistent high pressure system, which more or less has remained stuck over Russia since December. And while it's not uncommon for patterns to set up shop for extended periods of time due to natural cycles, this tenacity is extraordinary, to say the least.

It's clear that human-caused climate change plays a significant role in boosting the intensity of heat waves. Simply put, as average temperatures increase, extreme heat days become even more prominent.

In the Arctic, this impact is heightened due to a loss of ice and snow which typically reflects sunlight back to space. The decline in ice means more light is absorbed by the darker ground, spiking warming. The longer the heat dome lasts, the more it feeds back on itself, intensifying the heat wave.

"This warming increases the risk of extreme Arctic heat waves, such as this one, and moving forward over the next few decades," says Labe.

There may be an additional impact from climate change. Dr. Michael Mann is arguably one of the world's most respected climate scientists. In 2018 he published a study about a summer phenomenon he calls quasi-resonant amplification (QRA) in which atmospheric waves and jet streams tend to slow down or even get stuck, leading to a blocked pattern. This effect is most pronounced with more warming.

Mann told CBS News that while there is no evidence available yet for this specific event, "It is consistent with the overall phenomenon of more persistent extremes as a result of a slower, more meandering jet stream."

For decades, the Arctic has been warming much faster than the rest of the globe. Experts have frequently described that imbalance by saying that the Arctic is warming at twice the rate of the global average. But that is no longer accurate. Just days ago, Gavin Schmidt, the director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, corrected the reference by providing evidence that the rate of Arctic warming is actually three times faster.

The staggering pace of warming in the Arctic is causing systemic changes. Labe is amazed by the impact. "In response to the recent heat wave, the extent of Arctic sea has dropped like a rock in the Laptev Sea and the entire Siberian coastline. In fact, Arctic sea ice extent is melting several weeks earlier than average in this region!"

Over the coming week the core of the heat dome over Siberia is forecast to drift towards the North Pole, enhancing further melting. "The upcoming pattern looks particularly hostile for areas closer to the central Arctic Ocean. This will contribute to the formation of melt ponds (water) overtop of the sea ice, which can accelerate declines in sea ice extent later in the summer," explains Labe.

Recent heat is by no means restricted to the Siberian Arctic. So far in 2020, three cities in South Florida, including Miami, have experienced 121 record warm temperatures and only one record cold reading. In central Canada, temperatures this week along the shores of Hudson Bay are maxing out in the 90s. And in Norway, due to a stretch of unusual warmth well into the 80s, people are skiing on glaciers in bathing suits.

None of this comes as a surprise to climate scientists who have been sounding the alarms about the impacts of global warming for decades. This has led to extensive efforts to study past climates in order to help put the current warming into context.

For the study released Tuesday, a team of scientists affiliated with an international paleoclimate collaboration called PAGES (Past Global Changes), analyzed data spanning thousands of years into the past. The team engaged in an extremely exhaustive process reconstructing a 12,000-year temperature record ending in 1950. For the period before modern thermometers, they relied on a variety of temperature estimates based on what scientists call proxy records — clues like fossils buried in sediments, such as shells and pollen, that reveal what climate conditions were like in the ancient past.

The record revealed that the warmest 200-year period before 1950 took place about 6,500 years ago, when global surface temperatures were approximately 1.25 degrees Fahrenheit above the baseline, which is the 19th century average. Since that high point 6,500 years ago, the record shows the globe was steadily cooling. But that all changed abruptly in the past 150 years when, in that short time, humans have more than reversed thousands of years of cooling. Now global temperatures have risen about 2 degrees Fahrenheit above that baseline, leading to the conclusion that Earth is currently warmer than that warm period 6,500 years ago.

Prior to the starting point of the study 12,000 years ago, the Earth was engulfed in an Ice Age. Therefore, one could infer that temperatures are warmer today than they have been since before that Ice Age began, about 120,000 years ago. However, the study's lead author, Dr. Darrell Kaufman, a paleoclimate data specialist from Northern Arizona University, said the data is not precise enough to know for certain.

This new study by Kaufman validates work on past temperature reconstructions, like the now famous "hockey stick" graphic from Dr. Michael Mann, the director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University. The name of the graphic comes from its resemblance to a hockey stick showing a vertical leap in temperatures at the very end of the past 1,000-year temperature record. This new study shows that same effect is also apparent in both 2,000-year and 12,000-year time frames, as seen in the graphic below.

Mann said the new study lends even more evidence to how quickly humankind is reshaping Earth's climate.

He explained, "The 'handle' of the hockey stick just gets longer and longer with each new study and indeed there is a hint that current warmth now might be unprecedented since at least the last interglacial period more than a hundred thousand years ago."