Arctic melt opens door for big oil's next boom

WAINWRIGHT, Alaska Born and raised the son of an Inupiaq Eskimo whaling captain in this small village on the coast of the Chukchi Sea, Hugh Patkotak knows the water and he knows ice.

There are almost one hundred words for ice in the language of the Eskimos, he says. Words that describe ice floes that are flattened, thick and safe for walking; packed, soft ice which is perilous; and snow that floats on the ocean which is difficult for a wooden boat to push through in the spring.

Patkotak, chairman of the village's native corporation here, is also a search and rescue pilot. And he looks down on the tundra from his "bird's eye view," as he puts it, observing year after year as the ice begins to melt in the spring and summer and slowly returns in the autumn. And standing at the water's edge in Wainwright in late August and staring out at the dark sea, he said this summer he has seen few of the familiar icebergs on the horizon and no floating sea ice for hundreds of miles offshore.

"We have never seen a melt like this in our history," Patkotak said.

In these Alaskan waters of the High North, sea ice has melted at a record pace this summer, shattering a record set in 2007 and marking the greatest Arctic melt since scientists began monitoring it by satellite in 1979. Some scientists calculate it is the greatest melt in the history of humankind, and there is little disagreement that it poses a perilous development for the planet.

For Royal Dutch Shell and other oil companies, this melt is serving to open up the once ice-locked waterways that big oil will need to set up drilling platforms and staging areas to pull the crude and natural gas up from beneath the ocean's floor.

Shell spent four grueling years wrestling with federal bureaucracy and state politics and it sunk $4.5 billion to secure offshore lease holds over what geologists believe is a motherlode of crude in the rush for oil and minerals that is well underway here at the top of the world.

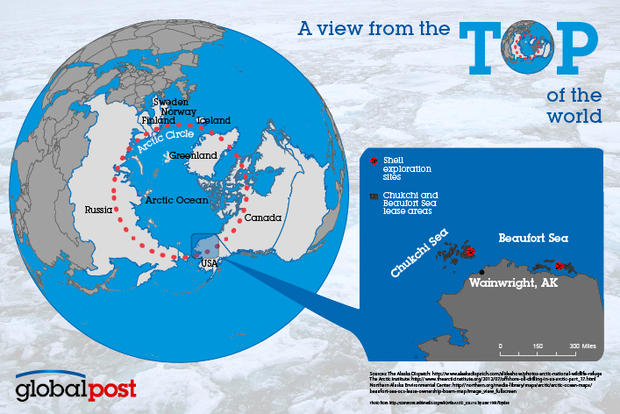

The historic melt has opened a battle that has the eight nations of the Arctic Circle -- the US, Canada, Russia, Sweden, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Finland -- all jostling for power and influence in the Arctic over what investment bankers view as the world's last, great emerging economy.

There's not just oil and natural gas, but also minerals including platinum, zinc, nickel and gold. There is the precious commodity of fresh drinking water. At stake are potentially trillions of dollars in profits. Also at stake are geo-political security in a time of diminishing resources, a delicate ecosystem that is crucial in cooling the planet and the traditional way of life for a native people who have everything to lose, and much to gain.

"We're worried. This is our home and these waters are our fields where we harvest our food. This isn't just a staging area for Shell, this is our home, and it is all about to change," says Patkotak.

- Fossilized forest may sprout again as Arctic warms

- Shell sues Greenpeace to stop protests against Arctic drilling plans

- Extreme weather could come with record Arctic Ocean ice melt

Dressed in a camouflage hunting jacket, he talks about the spring 'harvesting' of bowhead whales as long as 70 feet that roam the area and the hunt for caribou and polar bears. He looks out with uncertain eyes and remembers when there were icebergs visible at this time of year. And further out, he says, he can hear the hiss and pop of the melting sea ice as it disappears like clumps of white sugar dissolving into black coffee.

At the end of August, the US Department of the Interior approved Royal Dutch Shell to begin preliminary drilling. It came too late for the company to get going this year because the autumn ice began to return, but they announced they will lower their drill bits into the pristine waters next year after the spring when the melt is once again underway.

Environmentalists are bracing for this and fearful about a blowout of the magnitude of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon well, the worst oil spill disaster in American history. While much stricter regulations have been put in place for companies like Shell to have 'blowout preventers' and capping systems, the Arctic also raised the issue of how possible it would be to contain a large scale spill or blowout when the ice moved in. Environmental Groups from the Sierra Club to the World Wildlife Federation have sought to block or at least slow down Shell in its determined push to begin drilling.

A recent report on oil spill prevention in the Arctic commissioned by the US Arctic Program of the Pew Environmental Group was titled "Unexamined Risks, Unacceptable Consequences." The 135-page report did not mince its words on the dangers posed by oil operations in the Arctic.

It stated that "remote location, extreme climate and dynamic sea ice exacerbate the risks and consequences of oil spills while complicating cleanup." It stated that cleanup technology in icy waters was "unproved" and that a blowout "could devastate an already stressed ecosystem."

Shell Vice President Pete Slaiby, head of operations for Alaska, said he understands the concerns of native people as well as the fears of environmental conservation organizations that a catastrophic oil spill would be impossible to contain if it were to be trapped in the ice.

"I understand the fear, but I don't share it. And I'll explain why," Slaiby said, speaking in late August at the Arctic Imperative Summit, a gathering of global leaders in business, government, the environment and the native people of the Arctic.

"I'm here today because the company I work for believes as I do that offshore exploration can be done in a way that protects the environment. We can co-exist with the subsistence users and provide benefits and security to the entire nation and local stakeholders alike," said Slaiby, who is well known in Alaska as the face of confidence and candor for big oil's bold pursuit of offshore oil in Alaska.

And there is much to pursue. A 2008 study by the US Geological Survey found the Arctic to hold 90 billion barrels of oil and 1.7 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, or about 13 percent of the world's undiscovered oil and about 30 percent of its natural gas. Alaska has since the late 1970s benefited from large oil fields on shore in the North Slope. It has known about offshore Arctic oil since the late 1980s, but only now with advanced methods of drilling and the historic melt has it become feasible to go after it in a big way.

Vast oil fields, said by geologists to rival those of Texas and Saudi Arabia, lie about 60 miles off this tiny village on the Chukchi Sea. It is an irony as biting as the frigid temperatures that will set in here in the autumn that the very oil companies that contributed so much to global warming now stand to benefit from the dramatic melt it is causing.

This story originally appeared on Global Post, and was written by Charles M. Sennott