Arctic heat wave "essentially impossible" without human-caused climate change, study finds

Less than a month ago the world was shocked when the temperature in the Arctic Circle reached a record-breaking 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit. While remarkable in its own right, it was merely the exclamation point on an astonishing, prolonged and widespread heat event across all of the Siberian Arctic.

The extreme and unusual warmth in this region alarmed scientists worldwide, prompting a group of 14 scientists from six countries to collaborate in a study to figure how something this out-of-bounds could occur. On Wednesday, the researchers released their findings in a comprehensive climate attribution study, declaring, "This large-scale prolonged event would have been essentially impossible without climate change."

To put it into perspective, the team found that if, hypothetically, you lived in this region before around 1900, when human-caused climate change began to emerge, a heat event this widespread, prolonged and intense would only occur once every 80,000 years — or about once every 1,000 lifetimes.

The study determined the likelihood of experiencing a regional heat event of this magnitude today, as compared to 1900, is 600 times greater. And even in today's warmer climate, it would only be expected to happen once every 130 years.

"The findings of this rapid research — that climate change increased the chances of the prolonged heat in Siberia by at least 600 times — are truly staggering," said Andrew Ciavarella, the lead author of the research and senior detection and attribution scientist at the U.K. Meteorological Office.

The study examined the role of human-induced climate change in the likelihood and intensity of two specific events: the persistent warmth across the Siberian region from January to June, and the record temperature of 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit set at Verkhoyansk, Siberia, on June 20.

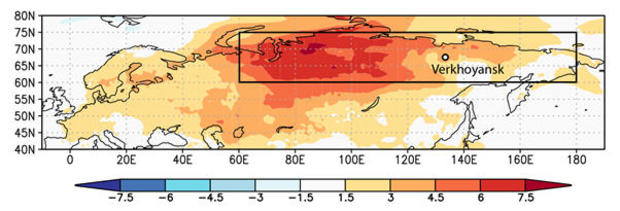

Over the first six months of this year, temperatures across the great expanse of Siberia — an area larger than the entire United States — averaged 10 degrees Fahrenheit above normal. The image below shows the study area (outlined in the rectangular box) and above-average temperatures in the orange-red shading, using degrees Celsius.

To illustrate the unusual persistence of the warmth, the visual below, from Arctic climate expert Zack Labe, shows the departures from average temperatures over Siberia for each month from January to June. The darkest shade of red indicates temperatures of 15 degrees Fahrenheit above normal.

To investigate the climate abnormalities, the research team examined both observational surface temperature records and recreated the climate using dozens of climate computer models.

To measure the effect of climate change, the scientists ran computer simulations to compare the climate as it is today with the climate as it would have been in 1900, when there was much less in the way of heat-trapping greenhouse gases and pollution.

On the question of how likely the 100.4-degree record in the town of Verkhoyansk was to occur in June, the study found it to be around a 1-in-140-year event in our current warmed climate, and several thousand times more likely than it would have been early in the Industrial Revolution, before humans substantially warmed the planet.

On the question of how likely a regional heat event of this year's magnitude is, the study found it to be a 1-in-130-year event in today's warmed climate — 600 times more likely than it would have been in 1900.

The study also found that from 1900 to 2020, human impact on the climate made the regional heat event approximately 4 degrees Fahrenheit warmer. And it estimates that in the future, if a similar heat wave were to occur three decades from now, in 2050, the intensity could be around 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer compared to 1900.

"These results show that we are starting to experience extreme events which would have almost no chance of happening without the human footprint on the climate system," explained Professor Sonia Seneviratne, from ETH Zurich. "We have little time left to stabilize global warming at levels at which climate change would remain within the bounds of the Paris Agreement."

The results of the study were so dramatic that even one of its most experienced climate attribution authors, Dr Friederike Otto, deputy director of the Environmental Change Institute at the University of Oxford, was surprised.

"It is by far the strongest change in an individual event I have seen compared to everything else I've studied so far," she said.

As a result of the remarkable heat and dryness, 8,000 square miles of Siberia have ignited in wildfires — significantly more fire coverage than last year up to this point. In June alone, these fires spewed 56 megatons of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — more than the yearly emissions of Switzerland. This leads to a dangerous feedback loop in which the extra carbon in the atmosphere further warms the planet.

The extensive heating is also causing another feedback loop in the Arctic by melting sea ice at a prolific rate. Right now, sea ice extent adjacent to Siberia in the Laptev Sea is not only in record decline, it has metaphorically fallen off a cliff.

Disappearing sea ice results in less sunlight being reflected from the light-colored ice back into space; instead, more heat is absorbed by the Earth's exposed, darker surfaces. As a result, the Arctic is warming three times faster than the global average. This phenomenon is called Arctic Amplification.

These drastic changes drive home the degree to which humans have become a force of nature, warming the climate through the burning of fossil fuels that release heat-trapping greenhouse gases and driving extremes previously unimaginable in our history.

"We are now seeing events far outside of what our societies are adapted to," said Otto. "Climate change is here now, it is not only a problem for someone else, somewhere else, but heat waves are threatening lives and livelihoods everywhere."

Although she doesn't feel climate change will wipe out the human race entirely, she warns it will lead to dangerous instability and increasingly compromise the most vulnerable: "It exacerbates inequalities and thus is a multiplier of other threats to our societies, as it is always those who are anyway marginalised that pay the highest price."