Inequality between red and blue states persists despite booming economy

The surprising results of the 2016 election have been explained, in part, as a story of economic malaise. But a year after that election, the divergence between red and blue states has only grown -- leading some to question whether the booming economy can bring a divided nation back together.

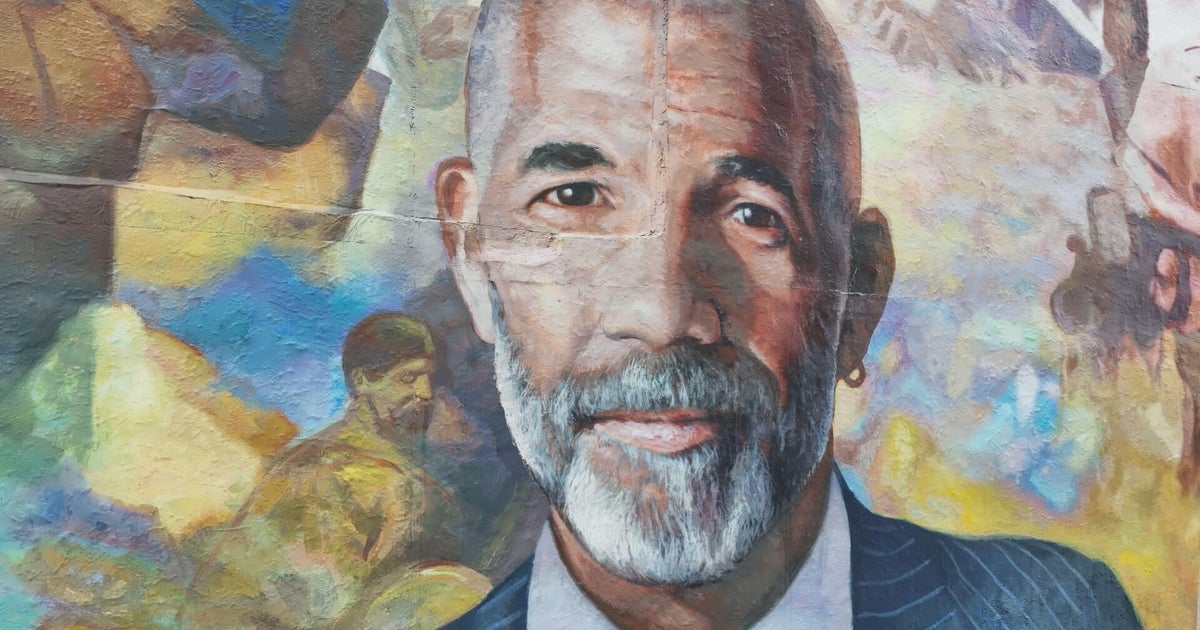

"Are some of those divisions healing because the economy is doing super well? It doesn't look like it," said Robin Brooks, managing director and chief economist at the Institute for International Finance.

The Institute conducted a state-by-state analysis and found that red states -- those that voted for President Donald Trump in last year's election -- lag blue states in a key metric: the portion of residents who are in the labor force.

That measure, called the labor force participation rate, includes people who are looking for work as well as those who are working in any capacity. And it's been persistently low in the current economic recovery. In fact, it's lower than at any point since women entered the workforce en masse in the late 1970s.

"When the financial crisis hit you had a ton of people basically exit the labor force," Brooks said. And while some of them have returned, they haven't returned equally. "For blue states, people are getting crowded back into the labor force, but it's not happening for red states," he said.

"Since 2014, we've had a very strong labor market, the monthly pace of jobs created has been running between 160,000 and 200,000, and it's just not working for red states," he added. The labor participation rates in those two sets of states have diverged in recent years: growing in blue states and falling in red. And that pattern has continued since the presidential election. "The robust economic picture at a national level is therefore not healing the red versus blue state divide," IIF wrote.

Over the past year, only a handful of red states have increased their employment-to-population ratio faster than the U.S. as a whole. These include Arkansas, Wisconsin, Florida and Georgia. The vast majority of red states have gotten their residents to work more slowly than the average, or actually decreased their employment-to-population ratio, despite maintaining the same level of economic activity.

The ongoing opioid crisis can account for some of these missing workers. But that alone doesn't explain the divergence between red and blue states, according to IIF, because the opioid crisis is hitting red and blue states fairly equally. And the workforce in red states isn't different, age-wise, from blue states, which could explain lower labor participation.

For Brooks, the difference lies in the red states' disproportionate dependence on a particular set of industries in decline. Red states are especially reliant on brick-and-mortar industries like retail and manufacturing, both of which have been facing headwinds lately despite the administration's economic policies. What some are calling the "retail apocalypse" has hit particularly hard. As e-commerce takes over for physical stores, the number of workers the industry needs drops dramatically (even though those jobs may pay better.)

While a typical department store needs about eight employees for every million dollars in sales it brings in, Amazon needs less than one for the same number, by Brooks' estimate.

"The net impact of e-commerce on employment is unambiguously negative. So it's unfortunate that the brick-and-mortar retail presence in red states is bigger," he said.

The same is true of manufacturing, which hasn't noticeably stopped its downward slide since last November. Blue states, meanwhile, have an above-average reliance on high-tech and medical jobs, which are growing faster than average.

But there's another possible reason that red-state participation is lagging. "[P]art of it is a story of austerity," said Josh Bivens, research director of the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank. While noting that the advantage blue states showed in the data appeared modest, Bivens said that states adopting cost-cutting measures could have put a damper on economic participation.

"Growth in state and local spending has been historically slow since the Great Recession, and this drag from state and local governments is probably the single largest reason why the economy overall took so long to recover," he said in an email. "I know that this state austerity has been most extreme in red states ([Gov. Sam] Brownback's [Kansas] being the real exemplar here), and, I would absolutely expect states that did deeper cutting to have their recoveries lag overall averages."