Civil rights leader Andrew Young says racism is based on fear, and George Floyd's death "touched the heart of the planet"

Former U.N. Ambassador and civil rights leader Andrew Young says once the world gets through the worst of the coronavirus pandemic and the economic crisis it's caused, "we're going to have to renegotiate the world order."

Young spoke with CBS News' Pamela Falk about the challenges facing the United States on the world stage and how the Trump administration is responding. He also reflected on racism, how the death of George Floyd "touched the heart of the planet," and what his experience working alongside Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., can teach today's protesters.

Young helped draft the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — passed 56 years ago this week — and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and he was with King in Memphis on the day of King's assassination.

He went on to an accomplished career as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives (1973-1977), U.S. ambassador to the United Nations (1977-1979) and mayor of Atlanta (1982-1990). Today he runs the Andrew J. Young Foundation to promote more just and prosperous communities by developing and supporting a new generation of leaders.

Here are excerpts of the interview.

CBS News' Pamela Falk: There have been protests about racism in just about every corner of the globe. Why is this message having such an impact around the world today?

Ambassador Andrew Young: It all comes back to these little cellphones. You know, I say that, when I was working with Martin Luther King we hardly had telephones in most of the residences where we stayed. And when I became mayor, there were four stories of mainframe computers. Now, in today's technology, this little device can do just about everything that all four stories of mainframe computers used to do. I think the availability [of] the cellphone as a low-cost means of communication has made the world smaller … and the internet means that almost nothing can escape the knowledge of the world. Everything goes global.

Since the death of George Floyd, protests have taken off in a way that they hadn't for so long, calling for racial equality. Why now?

The difference was that we had to watch it — watch the death of George Floyd. And it has the same impact everybody remembers, the little girl, the nude girl walking down the road in Vietnam crying. That image ended the war in Vietnam.

And George Floyd's death, the cold, callous way that it took place with other officers watching, and with people saying "get off him, get off him" around. … It was one of those moments that touched the heart of the planet. And life is not supposed to be that way.

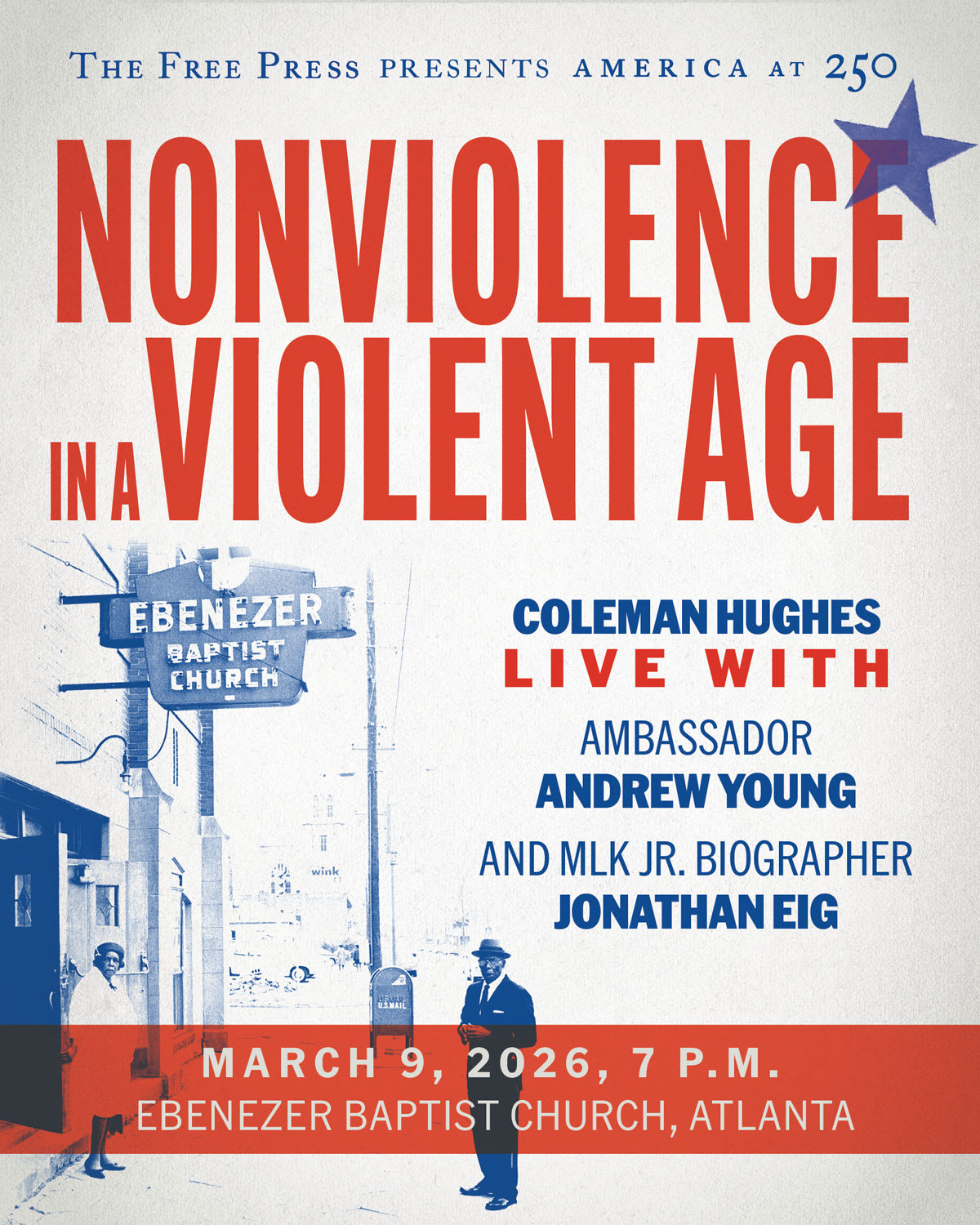

You worked so closely with Dr. King. Does his belief in non-violence and his preaching on civil disobedience still hold today? Is it an effective message?

Well, I think that the anger is not productive. One of the things that my father taught me at 4 years old was, "Don't ever lose your temper in a fight. Don't get mad, get smart." I happened to grow up in New Orleans; the Nazi Party headquarters [was] 50 yards from where I was born. And he explained to me that white supremacy is a sickness. You don't get angry with sick people. You kind of help them with their sickness and you don't, you just don't ever lose your temper in a fight. You lose your temper in a fight, you lose the fight. And I guess that was one of the reasons why you never saw, I don't think I ever saw Martin Luther King get angry.

Dr. King wrote about socialism. How do you think that applies today? Do you think that is still an issue in terms of wealth in this country and around the world?

That was one speech. One set of speeches. Martin Luther King was a capitalist. Martin Luther King's father started a bank. His grandfather was the treasurer of the National Baptist Convention with 6 million members. His family owned property. He was born with a guarantee that would have to get a Ph.D. degree in something; it was sort of decided by his family. His mother had a master's degree in music. His sister got a master's degree in music. He was born to education, and black privilege, as we say — as was I.

What do we need to do today ... for very poor societies, for the poor in America? What is needed to get where society needs to go?

I think the United States right now is committed to equal opportunity. I think we are also committed to a prison-industrial complex. Those two don't go together. And I think we've got to find a way.

A friend of mine says that his younger brother is in jail for drug problem that normally he should be in a treatment facility and should not be in a prison. It's costing $55,000 a year to keep him in prison. And she went to Yale Law School cheaper than that. She says he's smarter than she is. He, he just had a problem that she was able to escape.

I've visited prisons. I've always been impressed with the level of intelligence, the kinds of questions that I get, sensitivity and awareness of most of those people in prison. And those are people, if they were a different color or had been born with different parents…

Yet there are 2.2 million people in America's prisons. Now, I would give you the two points — point-two maybe need to be there. The two million should be educated and serving and competing and contributing. And that's something we've got to figure out how to solve.

What is racism a product of? Is it a product of economics? Is it hatred? Is it fear?

Fear is probably the most accurate description.

I remember meeting with [then South African Minister of Defense, later President P.W. Botha] who was considered the most powerful man in South Africa at the time. And he was the main obstacle to ending apartheid. And when I went to see him, one of the questions he asked me was: "How long do you think there'll be before the bloodbath?" And I said, what bloodbath? "Surely, these Black people are going to rise up one day and kill us all." I said no, I don't think so. And he got very agitated, he said, "How can you say that?" I said, I can say that because Gandhi formed the Indian National Congress here about the same time the African National Congress was formed. And he went back to India and liberated India, and I don't think a single Englishman was killed. I say now I have never heard any of my African friends talk about not working with [White] Afrikaners or getting rid of the Afrikaners.

Turning to the United Nations — what do you think in terms of the U.S.?

The United Nations' World Health Organization, this whole network of globalization, came out of the Second World War. It was a time when America wanted to be a leader. And America had learned from the First World War that it cannot get along unless we're somehow working for the global unity.

The full economy could be strong, and so they went to Bretton Woods [economic summit in 1944] and they made financial agreements, and those financial agreements made it possible for almost every economy in the world to grow 3% to 6% between 1944 and 1974. And that was the period in which the United Nations flourished. The World Trade Organization began to negotiate treaties.

Now, Americans now forget. One of the reasons why we were able to take the leadership was that we had won the war. We also had realized that we were the ones who had the most and we were going to let the rest of the world catch up. We had to pay a little more. So, we helped Japan. We helped Germany. We helped England. We help friends and enemies, friends and foe alike.

The one thing that the Trump administration has not realized yet, that this virus has taught us — that this little thing that we can't see and don't know much about has reminded us — that this is one world. And that there's no escaping it. We can't take many people to the moon. And somehow this little virus has gotten to everywhere, with everybody, and it reminded us: We are one family and, I think, under God. And it requires leadership from somebody.

So why do you think it's time for the U.S. administration to return and reinvest in multilateralism?

No, I think that it's not going to be investing in multilateralism. I think that there are others who are doing better than we are. When we recover from this virus, with 40 million people out of work, we're going to need help from our trading partners around the world. And that help — well, everybody's going to need help. And so we're going to have to renegotiate the world order. And I think that the present president doesn't think in those terms.

We normally got together, everybody was doing well. I think this time because of this virus, every economy in the world is going to be crippled. We're going to have to come together, deal to heal problems that are caused by combination of this health pandemic and the dramatic consequences of climate change.

Everything that they asked me to accomplish I did, because I practice what I call, with President Carter, the politics of respect. Diplomacy is personal. And we treated everybody that came from anywhere in the world to be part of our family and we developed honest, trustful relations. That really paid off. I think they will always pay off.

What is the highest point in your career?

The last point that I negotiated at the United Nations before I left was between China and Vietnam. That was the last war China had in 1979. China's been doing well because they have not had wars. We have been spending almost $6 trillion in various wars around the world. And that's the reason our economy's in trouble.

Heading back to solving problems without violence, getting back to working together with people and talking out differences is still the only way we're going to have one peaceful planet that's also prosperous. We have to include those who are left behind... We need to make the world work.