After initial praise, Governors Cuomo and Newsom face political heat over COVID-19 response

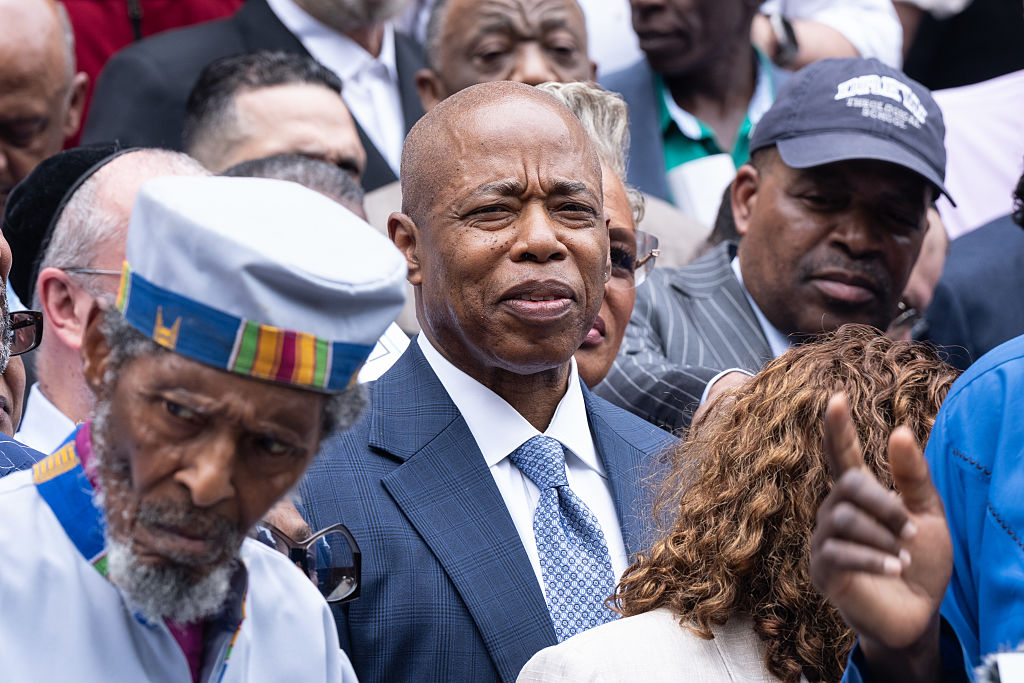

Two Democratic governors initially praised for their response to COVID-19 are now facing a backlash over their handling of the disease nearly a year after it began.

Californians were outraged when they saw photos of Governor Gavin Newsom eating at exclusive Napa Valley restaurant French Laundry while parts of the state were under lockdown, feeding momentum for the recall effort against him.

In New York, the FBI and Brooklyn federal prosecutors have opened a preliminary investigation over Governor Andrew Cuomo's nursing home policies after his administration hid the full number of COVID-19-related nursing home deaths for months.

Republicans and Democrats alike are outraged at him, and he's facing a possible rebuke from his own party and calls for his resignation from the GOP.

Cuomo's troubles escalated in January after New York Attorney General Letitia James issued a report saying nursing home deaths "may have been undercounted." The Cuomo administration then disclosed that nearly 15,000 nursing home residents had died, rather than 8,500 originally reported; the lower figure didn't include residents who had died in hospitals.

Last week, one of the governor's top aides, Melissa DeRosa, told lawmakers that the administration "froze" when state lawmakers and the Justice Department requested the nursing home data — it was worried the information would be "used against us."

Cuomo apologized this week for the "void" in information around nursing home deaths.

Democratic state Senator Alessandra Biaggi, a Cuomo critic, told CBS News that there is a "growing sentiment" among her colleagues that "the governor's expanded emergency powers have to be curtailed and taken back." The powers are set to expire at the end of April. Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins said in a statement on Wednesday, "we certainly see the need for a quick response but also want to move toward a system of increased oversight, and review."

Cuomo said on Friday that he told legislative leaders he wants to "take the tone down." But he believes some people are spreading misinformation about nursing homes, and he says he will "counter it aggressively."

One target of Cuomo's wrath is Democratic Assemblyman Ron Kim, who has been critical of Cuomo's nursing home policies. Last week, Kim accused Cuomo of calling him at home and spending "roughly ten minutes threatening my career," he said in an interview. Kim claims that Cuomo asked him to issue a statement defending DeRosa. A top Cuomo adviser accused Kim of lying and of having a "long, hostile relationship" with the governor.

"Every time we speak up, every time we criticize, we're punished or we're threatened and we're vilified in the media," Kim said.

State Senator Gustavo Rivera told CBS News he hasn't received any threatening calls from Cuomo, but he was contacted by Joe Percoco, a former Cuomo aide who was convicted of bribery in 2018. Rivera said he doesn't want Cuomo to run in 2022.

"His presence and his toxicity make it hard to govern this state," Rivera said. "It's either his way or his way."

A Siena College Research Institute poll released this week, conducted before DeRosa's comments, found Cuomo's overall approval rating at 56%, down from 77% last April. Sixty-one percent of New Yorkers approved of his handling of the pandemic, but just 39% think he has done a good job making all data about COVID deaths in nursing homes available.

Siena College pollster Steven Greenberg notes that Cuomo's drop in favorability is largely due to losing Republican support.

"There has been no scandal that has had a long term impact on the way New York Democrats feel about Andrew Cuomo," Greenberg said.

Cuomo has $17 million in his campaign account and easily defeated past primary challengers. A win in 2022 would make him the first New York governor elected to a fourth term since Nelson Rockefeller. Cuomo's father, former New York Governor Mario Cuomo, lost his bid for a fourth term to Republican George Pataki in 1994.

California Democrats have also battled with Newsom over COVID. The governor pushed to reopen schools this month, but the Democratic state Senate passed legislation setting an April target date, which Newsom signaled he'd veto. And state legislators have also criticized Newsom's sudden lifting of stay-at-home orders. But operatives like Los Angeles County Democratic Party Chair Mark Gonzalez say the critiques won't translate into support for Newsom's removal.

Freshman State Senator Dave Min called the recall an attempt to "manufacture a crisis" and tap into disaffection around COVID "to remove a governor they haven't liked from the beginning."

"No doubt, there is fatigue with Covid and a lot of the restrictions. But the silent majority is following the protocols, following the science. It's just kinda getting hijacked by this very loud, angry minority," Senator Min said.

Organizers of the recall movement say they've collected more than 1.6 million signatures. Signatures are due for verification by March 17 and 1.5 million are needed to initiate a special recall election.

As of February 5, they had submitted 1,094,457 signatures and had 668,202 signatures validated.

Gonzalez said while a recall election would "certainly leave a stain" on Newsom's reelection campaign in 2022, it won't "define his legacy."

Newsom was elected in 2018 with 62% of the vote, and he's now seeing a 46% to 52% approval rating. At the beginning of the year, he had $20 million cash on hand, an advantage for a potential recall campaign since there are no contribution limits in California faced with a recall.

"I wish we had recall ability in New York state," New York Congresswoman Elise Stefanik said at the California Republican Party Convention on Friday.

Cuomo and Newsom are fending off more salvos in part due to the attention they get as governors of big states, as well as the nature of constantly shifting politics around COVID, says Democratic strategist Jared Leopold.

"One day your state is at the bottom of the list in infections or vaccines, and the next day it's at the top," he said. "This crisis is not a short-term sprint, it's a long-term marathon. Coronavirus is going to define a lot of elections in 2022, but the question is where governors' legacies are on that issue in 2022, not where they stand in February 2021."

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story misidentified Democratic state Senator Alessandra Biaggi as Andrea Biaggi. The article has been updated.