America's "Forgotten War," south of the border

(CBS News) For the people of Mexico, the "Halls of Montezuma" are much more than the words of a song; they represent a humiliating military defeat at the hands of the United States in 1847. Not even the 1862 victory over France that Mexico celebrates today -- Cinco de Mayo -- is enough to fully heal the wound. Mo Rocca tells the story:

Every year, in a small cemetery in Mexico City, 750 unknown American soldiers who died in the Mexican-American War are remembered.

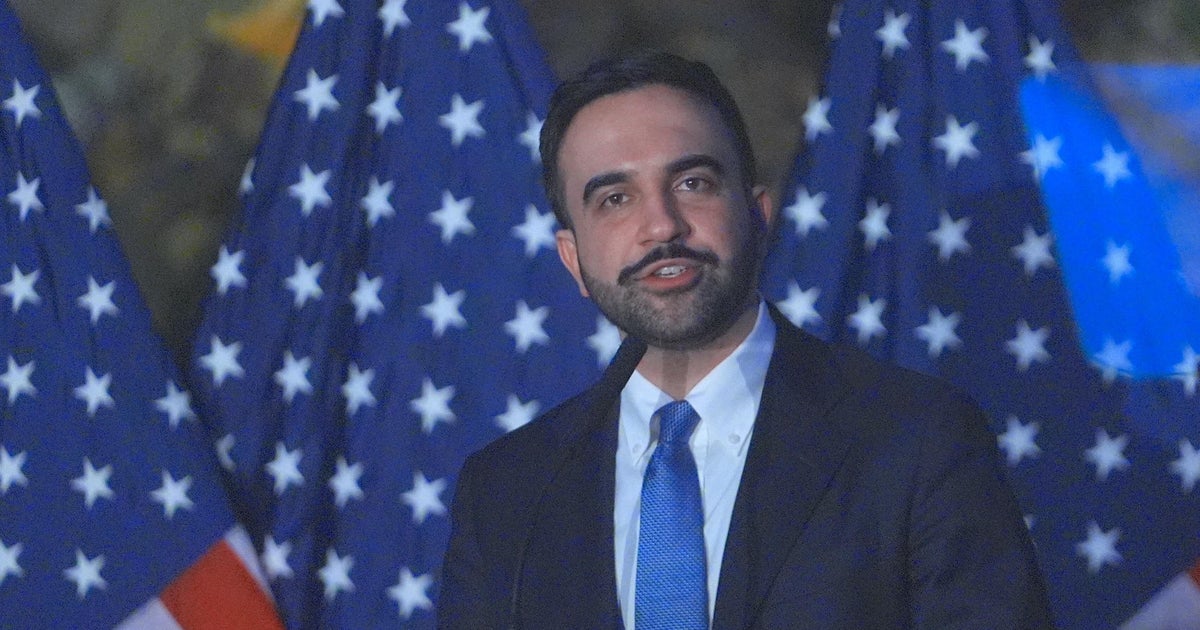

"That conflict marked a dark chapter in the long relations between our countries," said U.S. Ambassador Earl Anthony Wayne. He has to tread diplomatically over an issue that's still raw south of the border.

"Here in Mexico, of course, they remember it because large parts of the United States were parts of Mexico before that war," said Wayne.

But north of the border, the war is all but forgotten.

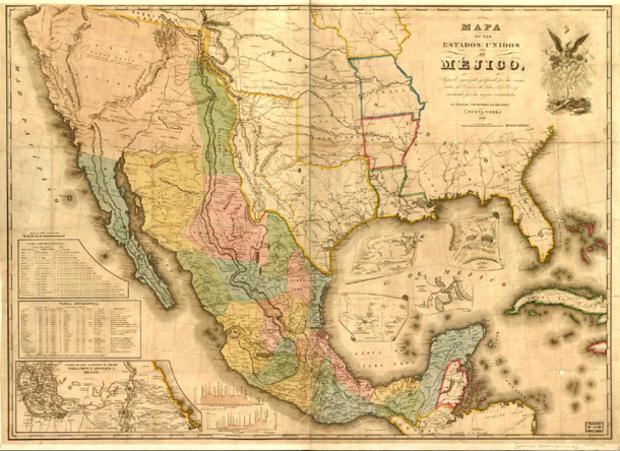

In 2008 an Absolut Vodka ad showing a map of Mexico stirred outrage in America: Was Absolut calling for Mexico to conquer the U.S.?

In fact, this is what North America looked like c. 1847:

Penn State historian Amy Greenberg says it was the first war in U.S. history that was fought for greed rather than principle: "There was no great ideological reason why we were going to war against Mexico. It was the first war that was started with a presidential lie."

Greenberg argues in her recent book, "A Wicked War," that the war was engineered by President James Polk.

"James K. Polk went to Congress and said American blood had been shed on American soil, but almost nobody except Americans claimed that the land where the blood was shed was actually American soil," Greenberg said. "When Zachary Taylor marched his troops between the Nueces and the Rio Grande, he was marching through land which everybody, including the residents of that territory, believed to be Mexican land."

"So they were basically looking for a fight?" asked Rocca.

"Absolutely. No question about it."

They were looking for a fight because President Polk had a vision for America called "Manifest Destiny."

"He really, firmly believed that it was America's destiny to spread to the Pacific and to take California," said Greenberg. "And he was going to do anything necessary to accomplish that goal. . . . God had singled him out to do this."

And so a long and bloody war began.

It would prove to be the training ground for many officers who later became famous in the Civil War.

For one of them, Ulysses S. Grant, the experience was troubling. In his 1879 memoir Grant wrote, "I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico."

"He also says that he thought so as a youngster, but he had not the moral courage enough to resign," said Greenberg.

Grant saw action in almost every major battle, as did Robert E. Lee -- the future Union and Confederate leaders fighting on the same side of a war that brought them all the way to Mexico's capital . . . and the "Halls of Montezuma."

Yes, the opening line of the Marines' Hymn refers to the battles that took place in Mexico City.

Marine Corps Lt. Col. William Fearn's own uniform is a memorial to the bloody struggle. "Corporals and above wear this red stripe," Fearn told Rocca. "It's by tradition, we call it the blood stripe."

Every weekend thousands of Mexican families and tourists gather in the city's vast Chapultepec Park, in the middle of which stands Chapultepec Castle -- once Mexico's West Point, where future officers came to be trained.

In 1847 this was the scene of a very different gathering, as American troops approached from the west and south of the castle.

Mexican General Santa Anna -- yes, the same Santa Anna who had massacred Texans at the Alamo 11 years earlier -- posted his troops alongside the cadets.

Salvador Rueda, director of the national historical museum at Chapultepec Castle, said the cadets were students at the military academy. "Boys between 14 through 19 years old. Teenagers," he said.

American troops used ladders to overtake what had seemed an impregnable fortress -- a devastating blow to the Mexicans.

"When Mexican troops withdrew from their position, the cadets stayed there and continued fighting," said Greenberg. "And according to history and lore, one of the cadets wrapped himself in the Mexican flag and threw himself over the castle walls rather than have the flag captured by Americans."

For Mexicans, the six cadets who chose to die rather than surrender have made this site hallowed ground.

Professor Fabiola Garcia Rubio says the monument of Chapultepec is a very special symbol for Mexicans, much like the Alamo is for Texans, and that from the fiery Battle of Chapultepec was forged a fierce sense of Mexican nationalism.

"So the emotions about that are still alive today?" asked Rocca.

"Yes. It's too alive and too emotional," said Garcia Rubio.

Despite the victory at Chapultepec, many Americans had soured on the war. It inspired the first national anti-war movement, when journalists reported atrocities suffered by Mexican civilians.

One staunch opponent of the war: a young Congressman named Abraham Lincoln.

His first major political address on the national stage was in opposition to the war with Mexico, said Greenberg -- and he paid for it. "He got a lot of flak from his constituency back home."

"Is there any evidence that he regretted it at all, his stand on the war?" asked Rocca.

"Absolutely not, absolutely not," replied Greenberg. "He never wrote a single word in opposition to what he said about fighting in Mexico."

With the American Army occupying Mexico City, the war ended with a treaty that realized President Polk's vision.

And that's not all: The U.S. still has possession of General Santa Anna's captured wooden leg.

"Mexico's asked for the leg back many times; Illinois won't give it up," said Greenberg. "The Fourth Illinois Volunteers took that leg as a trophy of war. It belongs to them."

So how do Mexicans today view the war?

"Well, as a disaster," said museum director Salvador Rueda. "Mexico lost half of their own territory."

For Rueda, the end of the war was the beginning of a long love/hate relationship between Mexico and the United States over what is known to them as Invasion Americana -- "American Invasion."

Greenberg says the conflict matters today because "A lot of people live in land that was taken from Mexico in this war, taken from Mexico, and they're not aware of that. I believe a lot of the immigration debate that's going on now operates in a vacuum, where people are not realizing that in fact Mexicans are here in lands that once belonged to Mexico."

For more info:

- Amy Greenberg, Penn State University

- "A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico" by Amy S. Greenberg (Knopf); Also available in trade paperback and eBook

- Chapultepec Park Trust

- Fabiola Garcia Rubio, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico

- Museo Nacional de Historia, Castillo de Capultepec

- Mexico City National Cemetery (American Battle Monuments Commission)

- Illinois State Military Museum, Ill. National Guard