American parents are spending billions on their adult children

From Ashton Kutcher to Bill Gates, there's a growing list of notable figures who say they will not be leaving an inheritance for their children. For the average American, there might not be much to leave behind when faced with the choice between supporting adult children or saving for retirement.

Parents are choosing to cover the costs of groceries, rent and cellphone bills for their adult kids.

A recent study from Merrill Lynch found that 79 percent of parents continue to serve as the "family bank" for their grown-up children, paying for big-ticket items like college and weddings, but also for smaller, everyday expenses. Parents of adult children contribute $500 billion annually -- twice the amount that they invest in their own retirement accounts.

Sixty-three percent of parents said in the study they have sacrificed their financial security for the sake of their children.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 34.1 percent of people aged 18 to 34 lived under their parents' roof in 2015. That's up from 26 percent in 2005. One in four young people living in their parents' home neither go to school nor work.

Denver tax and estate planning attorney Denise Hoffman White worries that propping up adult kids today hurts them tomorrow.

"You start to see adult children who are not being put in a position where they can be successful in their own right because they have a crutch which is different than an opportunity," said Hoffman White, who tries to train clients who are parents to talk to their kids about money the same way they teach manners or good grades.

Lorna Sabbia, head of Retirement and Personal Wealth Solutions at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, noted another possible outcome of supporting adult children.

"If you get to a point where truly your retirement savings or savings just in general is completely depleted to support your kids, ultimately your kids may actually have to provide financial support for you later on in life as well," she said.

Gary and Sandy Cooper's children may be grown up far beyond their years.

"You want to give … but sometimes giving them isn't actually helping them," said Gary Cooper, a private wealth adviser at UBS Financial Services. "Our job is to help them, not do for them, right?"

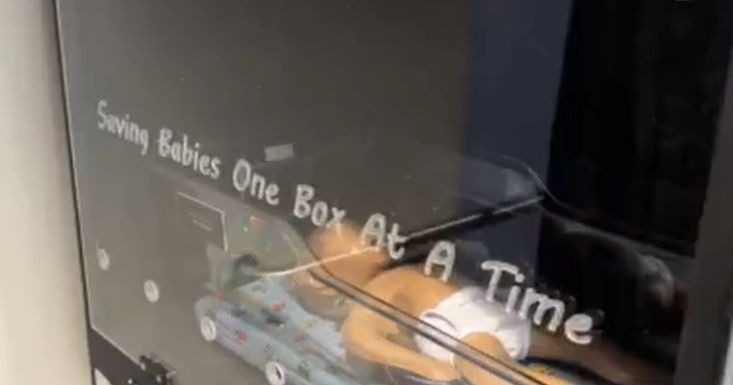

The Coopers try to teach life-long lessons in budgeting and money discipline with things as simple as a box of Oreos.

"You're welcome to eat them all tonight or you can allot them out and learn to make them last until the next time we go buy the next box of Oreos," said Sandy Cooper. "It's a concept of saving, of budgeting, of understanding -- that feeling of delayed gratification."

The Cooper kids have learned some lessons.

When 16-year-old Kyle wanted to buy the family car, he paid for it by maintaining a $1,000-a-year high school academic scholarship.

"I think the lesson was regardless of the money, if you work hard for something then you will be rewarded, whether it be by some physical thing or some emotional-- you'll be rewarded for hard work."

Kyle does part-time jobs like tutoring and shoveling snow to pay for extras like gas.

Nolan, 14, already knows his parents will only fund four years of college. After that, he's on his own.

"So, if my parents start us while we're young with the expectation that we have to work to get what we really want, that later in life we'll be able to prosper in that sort of environment," he said.

At age 11, Sofie is so financially farsighted she is already saving money for the apartment she will rent after college.

"Everybody is going to reach a challenge in their life where they can't ask for help, and they need to be able to do it by themselves, and by our parents making us grow up this way, it's going to help us be able to overcome that more than somebody who just gets stuff," said Sofie.

Sandy Cooper hopes these lessons will fortify her children for the future.

"So I think they'll have the intrinsic pride and motivation to deal with anything that gets thrown their way," she said.

Raising financially independent kids these days may be about teaching an old-fashioned lesson: earn before you spend.