Reflecting on the AIDS epidemic, 40 years after the first reported cases in the U.S.

A report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published on June 5, 1981 described a Pneumonia-like disease in five previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. While the disease was a mystery with no name back then, today the study is regarded as the arrival of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Dr. Michael Gottlieb, who published the paper 40 years ago, says the report sparked an "uncomfortable feeling" in the LGBTQ+ community about what would happen next.

"People tell me, particularly people in the LGBTQ community, tell me that they remember where they were when they read this publication, and they had an uncomfortable about what was coming on," he told CBS News' Elaine Quijano. "But the reaction of the general public was basically flat."

"It really didn't make it onto anybody's radar and it didn't make it onto the radar of most politicians."

Uncovering the origin of AIDS and how it is spread took years. By then, millions of people had been infected.

The disease was first detected in the gay community and was often referred to inaccurately as "gay cancer."

Gottlieb remembers his first patients like he just saw them yesterday.

"I remember those very first patients as well as I remember patients I saw yesterday," he said. "I remember their stories, their faces, I remember their occupations. I remember how they dealt with this undiagnosed illness that had no cause and no name with incredible strength, understanding, and grace."

It wasn't until 1985 that President Ronald Reagan addressed AIDS, when he defended his administration from criticism that it had inadequately funded AIDS research. By then, more than 3,600 Americans had died from the illness.

Poul Olson is the chief communications officer for GMHC, an organization founded in 1982 as Gay Men's Health Crisis, the first HIV/AIDS service organization in the world. He described Reagan's lack of action as a "dark time" in U.S. history.

"At that time, our government was not stepping up and assuming their responsibility for responding to this crisis, because it was primarily affecting a community that was deeply marginalized at the time," he said.

Sensing a lack of help from the government, AIDS activists – including a group that disrupted the CBS Evening News in one instance – pushed for change.

Along with activism, cultural flashpoints put AIDS into the public consciousness. The death of Hollywood actor Rock Hudson, a gloveless Princess Diana shaking hands with AIDS patients in the U.K., and Magic Johnson's shocking retirement announcement in which he revealed he is HIV positive all helped to increase awareness about the epidemic.

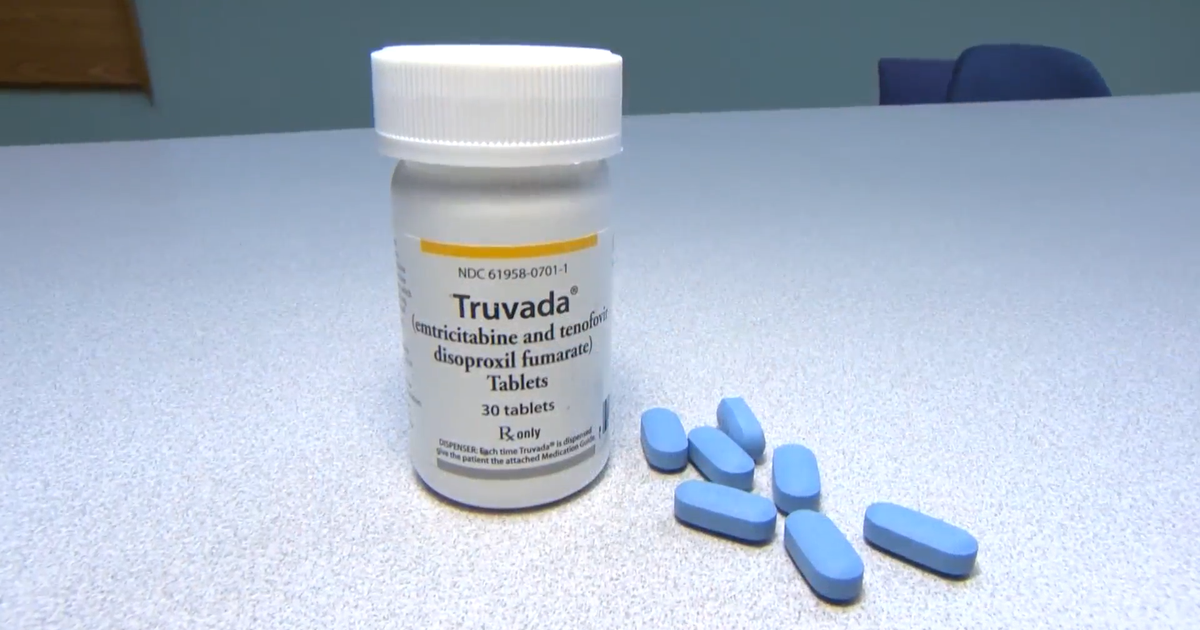

Then in the mid-199's came a medical breakthrough: the development of an anti-retroviral treatment that turned HIV/AIDS from a virtual death sentence into a manageable disease. Today, more than two-thirds of those living with HIV are receiving that treatment.

But the epidemic remains in what Olson calls "the last mile."

"I think the biggest misconception is that the epidemic is over," he said. "We still are seeing the unacceptably high numbers of new infections, especially in Black and brown and low-income communities that are disproportionally affected by other infectious diseases."

Though the epidemic is far from over, Dr. Gottlieb acknowledged the "remarkable developments" made in medicine over the past four decades as a small win in the fight against AIDS.

"Today a person age 25 diagnosed HIV positive and he's able to get on medication right away, is projected to have a virtually normal lifespan," he said. "That is a big, big change from what it was in 1981."