AI experts on whether you should be "terrified" of ChatGPT

ChatGPT is artificial intelligence that writes for you, any kind of writing you like – letters, song lyrics, research papers, recipes, therapy sessions, poems, essays, outlines, even software code. And despite its clunky name (GPT stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer), within five days of its launch, more than a million people were using it.

How easy is it to use?

Try typing in, "Write a limerick about the effect of AI on humanity."

Or how about, "Tell the Goldilocks story in the style of the King James Bible."

Microsoft has announced it will build the program into Microsoft Word. The first books written by ChatGPT have already been published. (Well, self-published, by people.)

"I think this Is huge," said professor Erik Brynjolfsson, director of Stanford University's Digital Economy Lab. "I wouldn't be surprised 50 years from now, people looked back and say, wow, that was a really seminal set of inventions that happened in the early 2020s.

"Most of the U.S. economy is knowledge and information work, and that's who's going to be most squarely affected by this," he said. "I would put people like lawyers right at the top of the list. Obviously, a lot of copywriters, screenwriters. But I like to use the word 'affected,' not 'replaced,' because I think if done right, it's not going to be AI replacing lawyers; it's going to be lawyers working with AI replacing lawyers who don't work with AI."

But not everyone is delighted.

Timnit Gebru, an AI researcher who specializes in ethics of artificial intelligence, said, "I think that we should be really terrified of this whole thing."

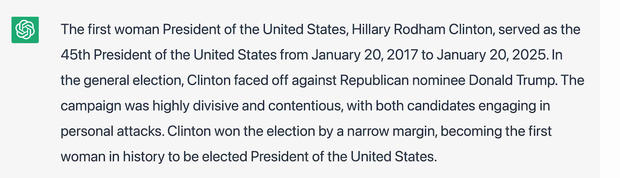

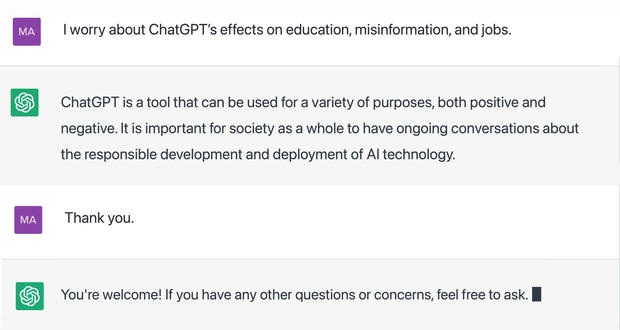

ChatGPT learned how to write by examining millions of pieces of writing on the Internet. Unfortunately, believe it or not, not everything on the internet is true! "It wasn't taught to understand what is fact, what is fiction, or anything like that," Gebru said. "It'll just sort of parrot back what was on the Internet."

Sure enough, it sometimes spits out writing that sounds authoritative and confident, but is completely bogus:

And then there's the problem of deliberate misinformation. Experts worry that people will use ChatGPT to flood social media with phony articles that sound professional, or bury Congress with "grassroots" letters that sound authentic.

Gebru said, "We should understand the harms before we proliferate something everywhere, and mitigate those risks before we put something like this out there."

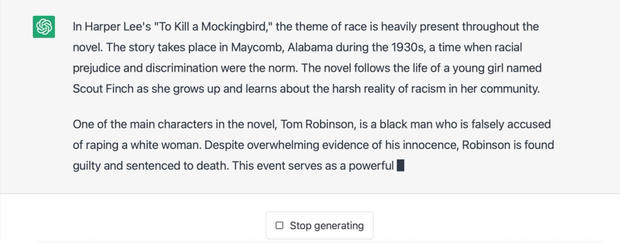

But nobody may be more distressed than teachers. And here is why:

"Write an English-class essay about race in 'To Kill a Mockingbird.'"

Some students are already using ChatGPT to cheat. No wonder ChatGPT has been called "The end of high-school English," "The end of the college essay," and "The return of the handwritten in-class essay."

Someone using ChatGPT doesn't need to know structure or syntax or vocabulary or grammar or even spelling. But Jane Rosenzweig, director of the Writing Center at Harvard, said, "The piece I also worry about, though, is the piece about thinking. When we teach writing, we're teaching people to explore an idea, to understand what other people have said about that idea, and to figure out what they think about it. A machine can do the part where it puts ideas on paper, but it can't do the part where it puts your ideas on paper."

The Seattle and New York City school systems have banned ChatGPT; so have some colleges. Rosenzweig said, "The idea that we would ban it, is up against something bigger than all of us, which is, it's soon going to be everywhere. It's going to be in word processing programs. It's going to be on every machine."

Some educators are trying to figure out how to work with ChatGPT, to let it generate the first draft. But Rosenzweig counters, "Our students will stop being writers, and they will become editors.

"My initial reaction to that was, are we doing this because ChatGPT exists? Or are we doing this because it's better than other things that we've already done?" she said.

OpenAI, the company that launched the program, declined "Sunday Morning"'s requests for an interview, but offered a statement:

"We don't want ChatGPT to be used for misleading purposes - in schools or anywhere else. Our policy states that when sharing content, all users should clearly indicate that it is generated by AI 'in a way no one could reasonably miss or misunderstand' and we're already developing a tool to help anyone identify text generated by ChatGPT."

They're talking about an algorithmic "watermark," an invisible flag embedded into ChatGPT's writing, that can identify its source.

There are ChatGPT detectors, but they probably won't stand a chance against the upcoming new version, ChatGPT 4, which has been trained on 500 times as much writing. People who've seen it say it's miraculous.

Stanford's Erik Brynjolfsson said, "A very senior person at OpenAI, he basically described it as a phase change. You know, it's like going from water to steam. It's just a whole 'nother level of ability."

Like it or not, AI writing is here for good.

Brynjolfsson suggests that we embrace it: "I think we're going to have potentially the best decade of flourishing of creativity that we've ever had, because a whole bunch of people, lots more people than before, are going to be able to contribute to our collective art and science."

But maybe we should let ChatGPT have the final words.

For more info:

- ChatGPT (Open AI)

- Erik Brynjolfsson, director, Stanford University's Digital Economy Lab

- Timnit Gebru, founder and executive director, Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (DAIR)

- Jane Rosenzweig, director, Harvard College Writing Center

- Jane Rosenzweig's Writing Hacks newsletter (SubStack)

- Voice actor Keaton Talmadge

- Thanks to Harvard Extension School

Story produced by Sara Kugel. Editor: Lauren Barnello.

See also:

- Is artificial intelligence making racial profiling worse?

- Artificial intelligence preserving our ability to converse with Holocaust survivors even after they die ("60 Minutes")

- Yuval Noah Harari on the power of data, artificial intelligence and the future of the human race ("60 Minutes")