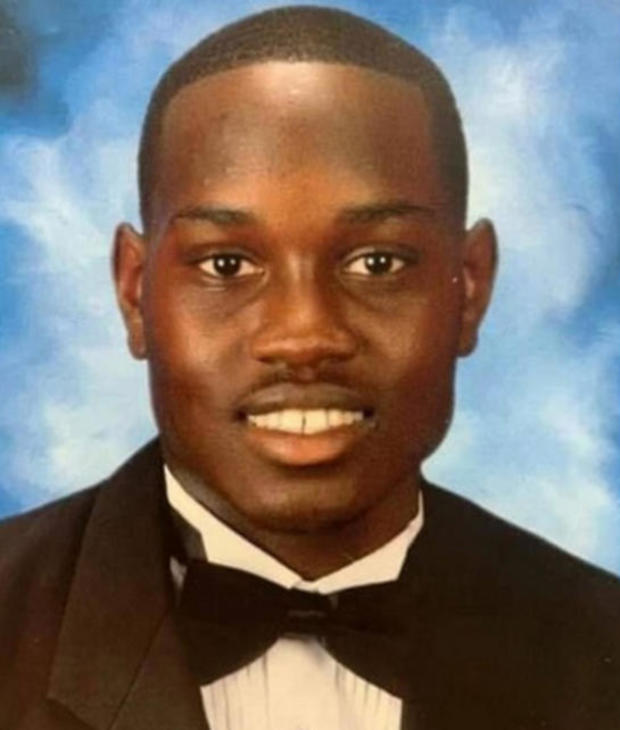

After Ahmaud Arbery killing, push for Georgia hate crime law sees "newfound resurgence"

There's a new push in Georgia for a state hate crime law after the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, an unarmed black man pursued by two white men and shot dead while jogging through a Brunswick neighborhood on February 23.

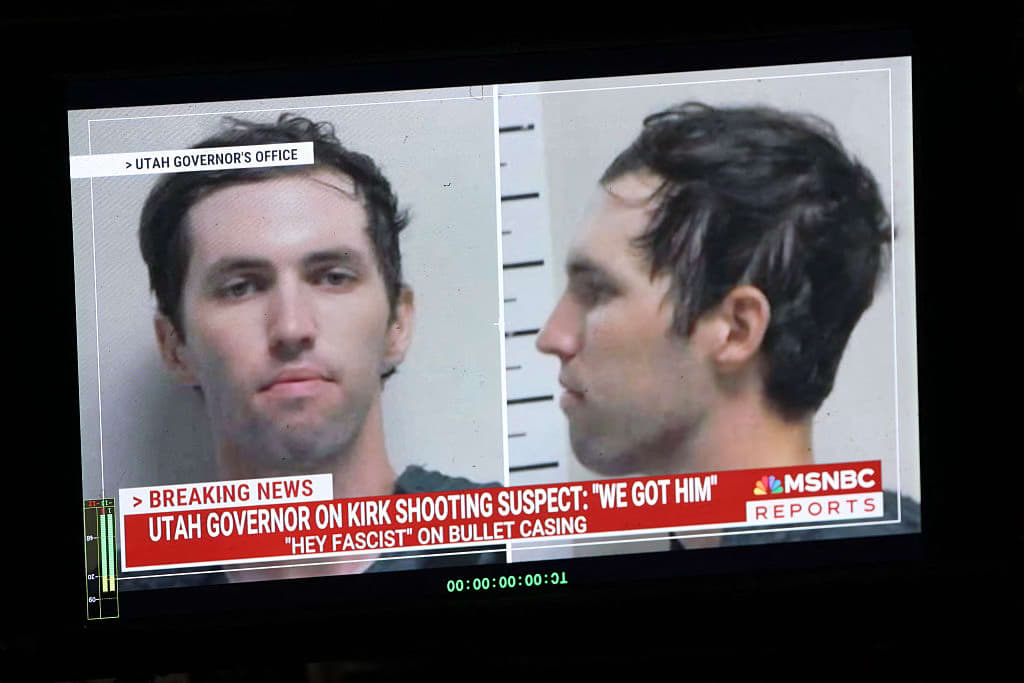

Gregory McMichael, 64, and his son Travis, 34, who told police they thought Arbery was a burglary suspect, were charged with Arbery's murder 74 days after his death. The killing, captured on a disturbing video, and the delay in the arrests, drew a national outcry.

Many have said Arbery was targeted because of his race, but Georgia is one of four states with no hate crime statutes, which generally allow for harsher sentencing for perpetrators of crimes ruled by a court to be bias-motivated. South Carolina, Wyoming and Arkansas also remain without hate crime laws, and some advocates also include Indiana among the list, calling a law passed in that state last year "uniquely and problematically broad."

Previous efforts to pass a hate crimes bill in the Georgia general assembly have faltered, but since Arbery's killing there's been a "newfound resurgence of interest in making sure Georgia gets this on the books," Georgia Representative Karen Bennett, chairwoman of the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus, told CBS News.

HB 426, the latest proposed hate crimes bill, was introduced with bipartisan support last year and passed the state house of representatives. But the bill appeared stalled in a state Senate committee when the legislative session was suspended in March over coronavirus concerns. Speaking at a press conference at Arbery's gravesite Tuesday, Georgia Representative Gloria Frazier called for the bill to come to the Senate floor for a vote when the Legislature resumes next month. Frazier, along with Representative Al Williams and Senator Lester Jackson, also called on Tuesday to rename HB 426 the Ahmaud Arbery Hate Crime Bill.

"The passage of HB 426, the hate crime bill, would allow citizens to feel safe knowing the state of Georgia does not accept or tolerate behavior rooted in hate," Frazier said.

The new urgency has come from legislators from both sides of the aisle. Speaking to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Georgia Republican Representative David Ralston, speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives, called for the state Senate to pass the bill "with no delay and no amendments."

"The time for being silent ended last week," Ralston told the paper. "It's time to do what's right. It's going to take some leadership and some courage, but I think it's time to act."

That Georgia is among only a handful of states without the statute "is a clear sign we are well past time and ready to get a hate crimes bill passed," said Allison Padilla-Goodman, vice-president of the southern division for the Anti-Defamation League. The ADL has joined a coalition of 35 advocacy groups known as Hate Free Georgia to call for HB 426 to pass. Padilla-Goodman said she's "cautiously optimistic" about its prospects.

"There's a long path ahead and there's a lot of work to do, but we were seeing politicians who maybe were not originally supportive of this stepping up and speaking out," Padilla-Goodman said.

The ADL has lobbied for years to pass a hate crimes bill in Georgia, she said. The Georgia general assembly in 2000 passed a hate crimes bill that called for enhanced sentencing for crimes motivated by "bias or prejudice," but in 2004, the bill was struck down by the Georgia Supreme Court as unconstitutionally vague.

The latest bill was crafted with more specific language. It would mandate enhanced sentencing for defendants convicted of targeting a victim because of their "actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origins, sexual orientation, gender, mental disability, or physical disability."

While states are the primary prosecutors of hate crimes, the federal government also has the authority to bring charges under the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. The Department of Justice can act as a "backstop" to prosecute hate crimes in states without the statutes or where state laws don't cover the crime.

State hate crime laws vary widely. While most include crimes motivated by bias over race, ethnicity or religion, some don't include bias crimes motivated by the victim's sexual orientation or gender identity, said Kami Chavis, professor of law and director of the criminal justice program at Wake Forest University.

The Department of Justice has said it is reviewing the Arbery case to determine whether federal hate crime charges are appropriate. It's also weighing a request by the Attorney General of Georgia to investigate the conduct of the first two district attorneys assigned to the case. They recused themselves amid questions over their links to Gregory McMichael, a former law enforcement officer, and handling of the case.

Even if Georgia passes the hate crimes bill, Chavis said she's troubled that it would be difficult to enforce. She said the "blatant disregard for prosecution" by the initial district attorneys points to the importance of the federal government's role in investigating hate crimes.

"This should not have taken two months, this should not have taken a video to have this prosecution," Chavis said.

Chavis said prosecutors typically need strong evidence to prove a crime was motivated by hate, something potentially lost by the delay.

"Make no mistake, I do not believe that if Ahmaud Arbery had been a white person jogging that he would have been treated that way," Chavis said. "But that's not going to be enough to prosecute those men for a hate crime. We need additional evidence that we might have had but for the complete disregard into investigating his death."

In a statement released to the Macon Telegraph, lawyers for McMichael said the public has rushed to judgment based on "a narrative driven by an incomplete set of facts."

Franklin Hogue said in a statement, "while the death of Ahmaud Arbery is a tragedy, causing deep grief to his family — a tragedy that at first appears to many to fit into a terrible pattern in American life — this case does not fit that pattern. The full story, to be revealed in time, will tell the truth about this case."

A state hate crime statute could be used to prosecute cases where the federal government typically wouldn't step in, such as a swastika painted on the door of a synagogue, said Padilla-Goodman. And there have been other troubling cases where a state law could come into play. Bennett cited the case of a white teenager accused of plotting an attack on a historically black church in Gainesville. Police said in November the girl's high school classmates told school officials the teen had detailed plans to kill worshippers in a notebook. The teen went to the church on a night when Bible studies are usually held, but no events were planned that day, the church's pastor told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Gainesville police chief Jay Parrish said at the time the girl wanted to target the church "because of the racial demographic of the church members." It's not clear how she allegedly planned to carry out the attack, but the paper reported she collected knives. She was charged as a juvenile with criminal attempt to commit murder, but hate crime charges were not an option under state law.

Representative Bennett also said a state hate crime law is important because of the message it sends.

"Georgia wants to send a message that we don't condone hatred of any kind in our society," Bennett said. "It's just important for the sanctity of humanity that we are able to recognize this evil in our society and to be able to say no to it and prosecute it to the fullest extent of the law."