Louisiana's health care deserts, racial discrimination and "fear" put women and babies at risk, advocates say

A Louisiana hospital sent a mom home "with prayers" while she was miscarrying, she said.

Kaitlyn Joshua was given an ultrasound at Woman's Hospital in Baton Rouge. They examined and monitored her. That's where she says the treatment ended.

"And so I said, 'OK - so is this a miscarriage?' And the young lady, she said, 'I-- I can't really tell you that right now. I don't know.' And I said, 'Well, what do you mean you don't know? We did the ultrasound,'" Joshua said. "I recall her saying 'we're just sending you home with prayers, we're going to hope for the best.'"

Woman's Hospital told 60 minutes: "It's complex...when diagnosis of early pregnancy loss is unclear, the standard of care is to wait."

The next day, when bleeding and cramping became unbearable, Joshua sought help from a second hospital, Baton Rouge General, where a doctor ordered another ultrasound

"She straight up said, 'This doesn't look like a baby at all. Are you sure you were ever pregnant? This just looks like a cyst,'" Joshua told 60 minutes correspondent Sharyn Alfonsi.

At both hospitals, Joshua said medical care providers avoided directly responding to her questions about whether she was miscarrying. Joshua said her discharge papers only noted "potential" miscarriage.

"I just have to believe, and I know, that it is just the vagueness of the abortion ban in this state that's caused so much fear around physicians doing their job," Joshua said.

A spokesperson for Baton Rouge General said every patient is different. They said that since the abortion ban began, "they have 'not changed the way they manage miscarriage or the options available" to treat them. The hospital's discharge instructions left Joshua with one option – to take Tylenol and monitor for worsening symptoms

Since the new law was implemented banning abortions in most cases, many physicians in Louisiana have been afraid to provide care typically used to treat miscarriages – like a D-and-C, a surgical procedure or a pill – because those same methods are used in abortions and can now be seen as illegal in Louisiana – potentially landing health care providers in jail.

Getting maternal care in the state was already challenging before the law passed. The U.S. holds the sad distinction of having one of the highest rates of pregnancy-related deaths in the developed world, according to the World Health Organization. Women in the U.S. are 10 or more times likely to die from pregnancy related causes than mothers in Poland, Spain or Norway. Some of the worst statistics come out of the South, where deep pockets of poverty, health care deserts and racial discrimination have long put women and their babies at greater risk.

Where you live can heighten the risk. A third of Louisiana's 64 parishes are maternal health care deserts without a single obstetric provider, according to the March of Dimes. More than 51,000 women in the state are left without easy access to care. They're three times more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes, according to a Tulane University study published in Women's Health Issues

Doctors are scarce in Assumption Parish, a rural county of 21,000. Moms Theresa Dubois and Brittany Cavalier, both expecting their third children, need to travel 45 minutes to the nearest pediatrician and up to an hour, 35 minutes to get to the closest OB-GYN.

"Oh, it's a nightmare," Dubois said. "It's a lot. It's a lot emotionally. It's a lot in the car. It's a lot just on your body, just waiting that long to get help."

The only hospital in Assumption isn't equipped to deliver babies. The moms will need to drive more than an hour to get to hospitals in Baton Rouge to give birth.

"I mean, we are supposed to be one of the best countries in the world. And you, you're just leaving the women out there to dry," Cavalier said.

Doctors, advocates and mothers are leading the charge to improve maternal health care conditions across the state. Dr. Rebekah Gee, an OB-GYN, former state secretary of health, and founder of Nest Health - a primary health service for families, has spent her career advocating for better maternal care in Louisiana.

As secretary of health, Gee worked with the state board that reviews every maternal death in Louisiana.The board found 80 percent of all pregnancy-related deaths in Louisiana were potentially preventable. Thirty nine out of every 100,000 mothers die during or shortly after childbirth in the state, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"The high C-section rates have contributed, the lack of access to well woman care before and after pregnancies," she said. "Fifty percent of the time women don't get that postpartum care, which means they have untreated hypertension, untreated diabetes, untreated depression. The fact that we have racial bias in health care. And so all of these things are compounded and especially worse for low income women."

Black women are among the most at risk; they're up to four times more likely than white women to die during or after childbirth in Louisiana, according to the state Department of Health. Dr. Gee said that when she was medical director, workers were told they were not allowed to show medical data that showed health disparities.

"Because the political establishment didn't want to admit that there were disparities," she said.

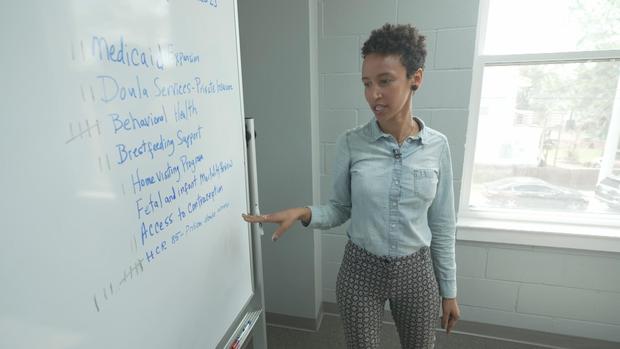

Those disparities are why labor and delivery nurse Latona Giwa co-founded the New Orleans-based Birthmark Doula Collective in 2011. Last year, they worked with 2,000 mothers.

"We live in a country that doesn't guarantee insurance coverage and health care to everyone, there is different and discriminatory care," Giwa said. "Black and Brown people are more likely to be on Medicaid. They're going to practices that are busier, that take more patients. And that's where the doula comes in."

Recent studies show better birth outcomes for Black women who've had doula care. Birthmark's work in Louisiana caught the attention of maternal advocacy group Every Mother Counts, which was founded by model Christy Turlington. Turlington became an advocate for mothers after her own complications during childbirth. Her organization focuses resources on states that have high rates of maternal mortality, she said.

"The U.S. is one of eight countries that have actually had an increase in maternal mortality," Turlington said. "So we're certainly at the bottom rung."

Last year, Every Mother Counts distributed more than $1 million to groups focused on strengthening maternal care in the U.S. It's a mission that became even more difficult last summer. After Roe V. Wade was overturned by the Supreme Court in June, Louisiana implemented a sweeping abortion ban. The ban set off a domino effect across the state.

The organizations advocating for moms face tough challenges. Last summer, Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry sent a letter to doctors about the new abortion ban, leaving many maternal health care providers in the state feeling paralyzed.

Dr. Jennifer Avegno , an ER doctor and current director of the New Orleans Health Department said Landry's letter made doctors scared to act. When 60 Minutes reached out to multiple providers across the state about maternal care, employees said they were afraid to speak out. Dr. Avegno felt she needed to make her voice heard on the issue.

"We cannot afford to backslide on maternal morbidity and mortality," Avegno said. "If we can't support moms, and they have adverse outcomes, or they die, that affects a family for its entire life. I am concerned that we are gonna see a worsening of our morbidity and mortality rates-- simply because of access and simply because of fear."