Feel again: Advancements in prosthetics limb technology allow feeling, control

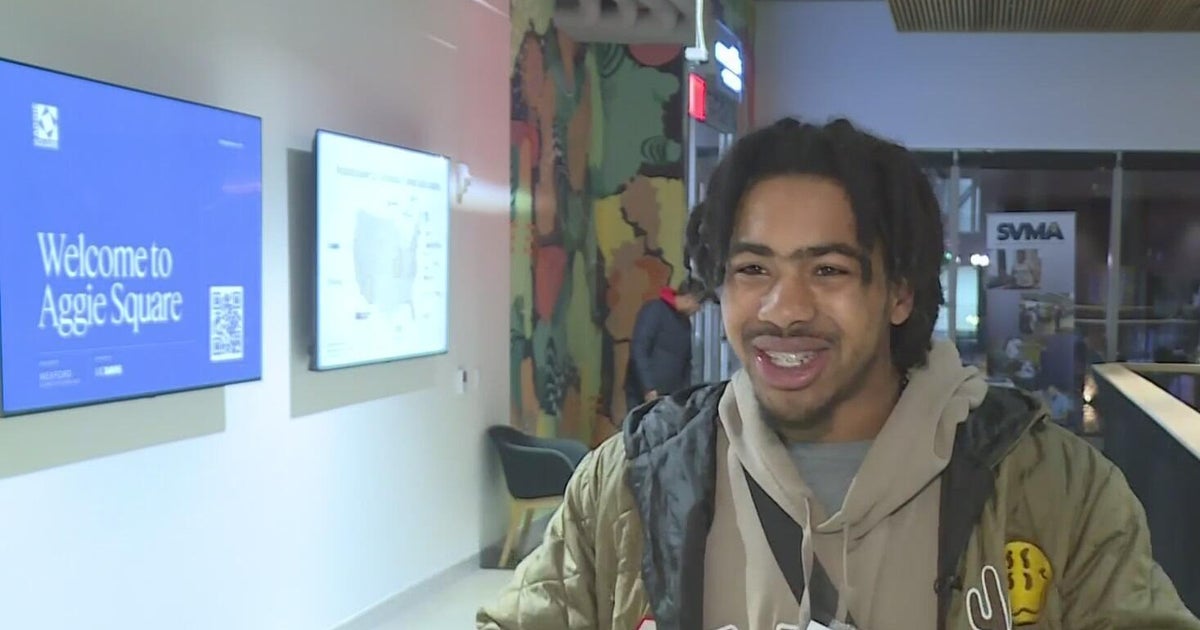

We don't often think about how the sense of touch makes our lives possible. We grip a paper coffee cup with perfect force to hold it but not crush it. Our feet always find the floor. But for people with artificial limbs, or those with spinal injuries, the loss of touch can put the world beyond their grasp. Seventeen years ago, the Defense Department launched a $100 million project to revolutionize prosthetic limbs. The robotics you're about to see is amazing- but as we first reported earlier this year, even more remarkable is how the 'feeling of feeling' is returning to people like Brandon Prestwood.

Brandon Prestwood: For me, it was, it's a battle if I wanted to live or die.

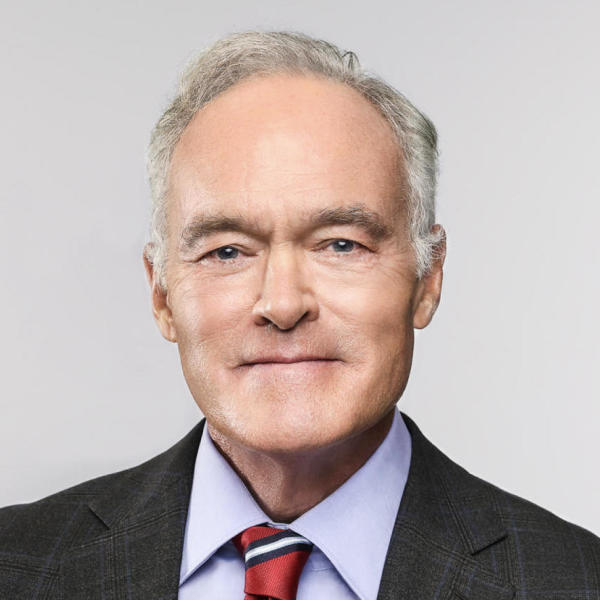

Scott Pelley: You weren't sure you wanted to live?

Brandon Prestwood: No. I didn't know if I wanted to or not.

Brandon Prestwood's battle began with the loss of his left hand. In 2012, he was on a maintenance crew reassembling an industrial conveyor belt when someone turned it on.

Brandon Prestwood: And my arm was dragged in pretty much up to the shoulder. It crushed my bones in my arm and fed my arm through a gap of about one inch.

Scott Pelley: How did they save your life?

Brandon Prestwood: The other maintenance guys jumped in. They started basically takin' the machine back apart. Once we got it back apart, I could look in and see what was there. And one of the gentlemen was a Vietnam veteran...

Scott Pelley: And the Vietnam veteran knew what to do.

Brandon Prestwood: yeah.

The Vietnam veteran knew tourniquets, but Prestwood lost his hand and couldn't return to his job.

After four years with a hook, he told his wife, Amy, he wanted to volunteer for experimental research involving surgery at the V.A.

Amy Prestwood: I was not 100% on board to start with. But I knew he had his mind set that he was-- he had to do this. And I couldn't hold him back.

Six years later, thanks to Defense Department and V.A. Projects, Prestwood controls this hand with nothing but his thoughts.

Lab tech: Everything still feel good?

Brandon Prestwood: Probably, when I get her turned around here...

Electrodes, implanted in muscles in his arm, pick up his brain's electrical signals for movement. A computer translates those signals to the hand. Sensors in the plastic fingers are connected to nerves in his arm to return a basic sense of touch which he can demonstrate with his eyes closed.

Biomedical engineer Dustin Tyler leads this research at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland V.A.

Dustin Tyler: Touch is actually about connection, connection to the world, it's about connection to others and it's a connection to yourself right? I mean, we never experience not having touch. It's the largest sensory organ on our body.

Tyler first attempted an artificial connection in 2012. He switched it on in a volunteer and wondered what would happen.

Dustin Tyler: So I was concerned, would it be his whole hand? Would it be painful? Would it not feel anything? We had no idea. So, one of those big moments in my career was he came in, we first turned on the stimulus, and he kinda stopped for a second and he goes, "That's my thumb. That's the tip of my thumb.

Scott Pelley: This happened right away?

Dustin Tyler: First time.

Scott Pelley: It didn't require any training of the brain.

Dustin Tyler: No. That was the beauty of it, "My thumb."

Brandon Prestwood remembers the instant it happened to him.

Brandon Prestwood: "That's my fingers." I am feeling my fingers that I don't have anymore. I'm feeling them.

A definite feeling, he told us, but different.

Brandon Prestwood: It doesn't feel exactly like my right hand. It's a tingling sensation. It's not painful. It's kind of like, if your hand's been asleep, right at the end, right before it wakes up, that very, for me, it's pleasant, it's a pleasant tingling.

A tingling that's light with a light touch but grows stronger the harder he presses. Eyes closed, he can pinch a cherry firmly enough to pull it from its stem but not crush it.

I had to use my lightest touch with an empty egg shell.

Scott Pelley: So if I hold this right here--

Brandon Prestwood: I can feel that. I feel it here and here.

It's a feeling more than a decade in the making.

Scott Pelley: At the beginning of this research, how did you even imagine that this would be possible?

Sliman Bensmaia: I didn't imagine. I imagined it was not going to be possible.

Sliman Bensmaia, at the University of Chicago, is among the world's leading experts on the neuroscience of touch. In 2008, he joined the Defense Department's project to revolutionize prosthetics but he didn't think the Pentagon knew what it was up against.

Sliman Bensmaia: There are 100 billion neurons in the brain interconnected with 100 trillion synapses. I mean, the human brain, it's like the most complex system in the known universe.

Too complex, he believed, to target electrical stimulation to exactly the right neurons.

Sliman Bensmaia: And when we electrically stimulate, we activate hundreds, thousands of them at the same time, in ways that would never happen naturally. It just seemed like that very impoverished interface with this nervous system would never do any-- be able to do anything useful. And it turns out I was wrong.

He was proved wrong by his own research…

Scott Imbrie: How ya doin' Scott, nice to meet you.

Scott Pelley: Nice to meet you, Scott.

…with volunteers including Scott Imbrie

Scott Pelley: And you can feel that?

Scott Imbrie:I feel it on my fingertips.

...whose movement and sense of touch are limited by a spinal injury from a car accident.

Computer ports in Imbrie's skull are wired to the motor and sensory parts of his brain. Electrodes pick up the brain's electrical signals that were intended for the muscles. A computer translates those signals to the robot arm.

We first saw this brain/machine interface ten years ago at the University of Pittsburgh. But, back then, there was no sensation.

Scott Imbrie: Index finger...

In collaboration with Pitt, neuroscientist Sliman Bensmaia showed that signals for touch could be returned to the brain.

Scott Pelley: How can you possibly know what part of the brain is the tip of the index finger?

Sliman Bensmaia: We took Scott and we put him in a scanner, a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner. And then we had him imagine moving his thumb, imagine moving his index imagine moving his digits as we monitored his brain activity. And lo and behold, the sensory and motor parts of the brain that are involved in the hand, lit up.

There are challenges. eventually the brain builds scar tissue at the implants limiting the motor electrodes. But one patient's implants have lasted eight years and counting. Scott Imbrie's have been working more than two years.

Scott Pelley: You have been a subject of this work for years now. And I wonder why.

Scott Imbrie: I wanted to have someone else to have the opportunity to become independent again.

Scott Pelley: The most meaningful work of your life?

Scott Imbrie: Yes, sir. 100%.

The greatest independence might be no prosthetic at all. And we saw this astounding possibility with a pioneer, Austin Beggin. His brain impulses are routed, not to a robot, but to implants in his own arm that fire his muscles.

Scott Pelley: What function did you have in this hand before the implants?

Austin Beggin: Oh, absolutely none.

Scott Pelley: Nothing? You couldn't move it at all?

Austin Beggin: No. So, the only thing I can do really is shrug my shoulders and kinda shift 'em. Unfortunately, that was all that came back after my accident.

His accident was on a vacation celebrating his college graduation. Diving into a submerged sandbar left him quadriplegic. Now, motor and sensory impulses flow through the ports in Beggin's skull and a computer, bypassing his damaged spine.

The research is led by Bolu Ajiboye, a biomedical engineer at Case Western Reserve University.

Bolu Ajiboye: Our goal is to restore complete functionality of the upper arm including dexterous hand function and the ability to reach out so that Austin and others who've suffered, you know, severe spinal cord injury can regain some level of functional independence.

The cradle under his arm only supports the weight—all of the motion is his own. it takes effort. He has to concentrate—

The computer needs frequent adjustment. But his parents Shelly and Brad showed us where this could lead.

Beggin retained limited feeling after his injury which makes him ideal for evaluating the artificial sense of touch. His motor skills continue to grow.

Austin Beggin: So if I can extend first. Let me open my hand for ya and squeeze around it. You'll feel me really start to dig in right there.

Scott Pelley: You got a grip.

Austin Beggin: Yeah. (Laugh) It really is. And let go and I'll bring the arm back up.

Scott Pelley: Congratulations.

Austin Beggin: Yeah. Thank you. Thank you--

Scott Pelley: Amazing.

Austin Beggin: --so much.

Amazing advances are coming quickly. Danny Werner lost his foot in vietnam. But 47 years later, he was reconnected to touch in an artificial foot which helps him balance, climb stairs and walk on uneven ground. Brandon Prestwood's next device will replace some wiring with bluetooth connections. The cost of his experimental rig and surgery is estimated at roughly $200,000. But an eventual commercial system may cost significantly less while delivering moments that are priceless.

Scott Pelley: What did that mean to you to feel Amy's hand in yours?

Brandon Prestwood: The world. I was a whole person again. I didn't have to worry about those dark thoughts creeping back in.

Amy Prestwood: It's just given me back my husband who means the world to me. He's himself again.

'Himself' because the feeling of feeling is so much of what makes us human. Maybe that's why, when we see a tender moment, it is said to be "touching."

Brandon Prestwood: I love you.

Produced by Aaron Weisz. Associate Producer, Ian Flickinger. Broadcast Associate, Michelle Karim. Edited by Jorge J. García.