Adoption agency's demise sheds light on troubled industry

When Christa Trinler and Wayne Walrath decided in 2016 to adopt a child, the upstate New York couple braced themselves for potential hurdles, including an average wait of up to two years and costs that can easily exceed $45,000. One scenario they did not consider: that the adoption agency they were working with -- at a cost of nearly $2,000 a month -- would suddenly and without warning shut its doors.

Like thousands of others across the U.S. who had sought to adopt through the Independent Adoption Center (IAC), the couple got the distressing news by email. IAC, a nonprofit agency in Concord, California, that had been in business for 34 years, was bankrupt and would close its doors effective Jan. 31.

The blow was not only emotional, but also financial. “If we don’t get that money back, to have to start paying another agency is big for us,” Trinler, 47, told CBS MoneyWatch.

“When I signed with the agency I felt hopeful, I wasn’t sad about the situation, or beating myself up because I couldn’t get pregnant anymore,” she added.

After marrying in 2007, Trinler and Walrath had tried to get pregnant for several years before exploring their options with fertility doctors, before ultimately deciding to adopt. That dream is now in tatters.

Among the larger private adoption agencies, California-based IAC, which had offices in eights states, said in its Feb. 3 bankruptcy filing that 1,886 adoptions in varying stages of the process had been affected by the agency’s closure. A week later, it updated that count significantly to more than 3,200 families and individuals.

The landscape has changed in recent years for IAC and other adoption agencies, which face growing demand for infants but a decline in the number of available children. One reason for the dwindling pool of inflants was a 2013 ban by Russia of the country’s children by U.S. families. Other countries have also imposed tighter restrictions on adoptions.

Domestically, fewer single mothers are putting their infants up for adoption because of the declining social stigma against women raising kids on their own. The opiod epidemic in the U.S. is also increasing the number of babies with health issues, further reducing the pool of infants who might otherwise have been adopted.

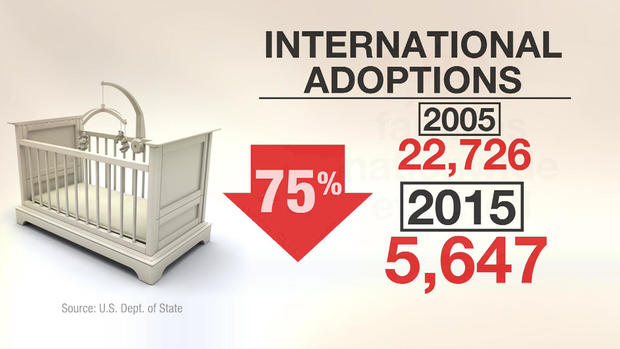

Private infant adoptions in the U.S. have declined nine-fold since the early 1970s and now number about 14,000 a year. International adoptions peaked in 2004 at just under 23,000 and dropped from there, falling to roughly 5,600 in 2015, according to the U.S. State Department (see chart below).

Of the more than 100 adoption agencies to close or consolidate in the last 10 years, most specialized in international adoptions, said Chuck Johnson, president of the National Council for Adoption. “As the number of intercountry adoptions declined by 75 percent, they couldn’t stay open.”

But IAC’s abrupt exit also raises questions about its management, along with larger issues about the lack of rules for how agencies manage clients’ money.

Dawn Smith Pliner, director of Friends in Adoption, a nonprofit agency based in Poultney, Vermont, and Ballston Spa, New York, said the writing should have been on IAC’s wall well ahead of its notifying clients at the end of January, and the agency could have taken steps to lessen to the blow to prospective parents.

“When IAC realized it was no longer making enough placements on an annual basis, it should have said, ‘We’re not making as many placements, so we’re going to slow down the number of pre-adoptive families that we bring into the agency’,” Smith Pliner said.

She speaks from experience. In 1996, her agency nearly closed. “I said no new families until we catch up,” Smith Pliner recalled. Friends in Adoption made a point of informing families that adoptions were likely to take longer than expected, and all of its clients stayed in the program.

“There is a very kind, humane way to do it, and IAC should have taken the time to make a plan,” said Smith Pliner, who noted that one agency often takes on another’s clients when another agency is winding down its business. “They could have handled it differently.”

IAC, which in a statement blamed “societal changes” for its closure, declined further comment.

The California Department of Social Services (CDSS), which licenses adoption centers in the state, is now sorting through hundreds of boxes of IAC’s documents to unravel the status of ongoing adoptions. “We have adoption agencies that close, and typically they would be working with another agency to take on their cases,” said Michael Weston, a spokesperson for the CDSS. “Typically, they would transfer closed files to the state.”

IAC appeared financially sound as recently as 2014, according to documents filed with the IRS. Yet by the time it abruptly pulled the plug it was bringing in far more new prospective adoptive parents than it could reasonably match with birth mothers in the time claimed. Payments from new clients appeared to be used to recompense earlier clients, including those asking to be reimbursed for having waited longer for a baby than the 18-month average touted by IAC.

Given IAC completed less than 200 adoptions a year, there was “a significant imbalance between the number of adoptions the agency could do and the number of prospective adoptive parents waiting in line,” said Johnson. “Maybe IAC wanted to give their birth parents hundreds of options for selecting the family that would adopt the baby. Or, if you’re a skeptic, maybe they needed prospective adoptive parents to be paying application and home study fees, which some could argue was a Ponzi scheme.”

“For years, they hovered around 160 or so annual adoptions. If they never took another application, it would take them eight years to serve the number of clients they had waiting,” said Johnson, who based the estimate on IAC’s initial tally of 1,886.

“It appears that they may have taken fees from one family to use it as cash flow to complete adoptions for other people. In many instances there are no requirements to put fees into an escrow account and draw it down as discreet services -- for instance, completing a home study -- are performed,” said Maureen Flatley, a political consultant who for years has advocated for federal oversight and reform of child welfare and adoption.

“When I got the email that they filed for Chapter 7, I had no reason to think they were in financial trouble,” said Trinler, a freelance actor and producer. “When I opened it, an urgent message from IAC, I thought, ‘Did I open my spam folder? This doesn’t compute’.”

After all, Trinler and her software developer husband had done their homework. “It was a long road of researching various agencies and options, making the decision, and figuring out how to financially afford the endeavor,” Trinler said in a Facebook post. “I thoroughly vetted them through lawyer contacts, other adoption professionals and previous clients.”

Trinler recounts that when she and her husband contacted IAC in late 2016 to initiate the adoption process, they were told prices were going up the following month by $20,000 or more, giving impetus to their decision to sign up immediately at the lower rate. They signed a contract with the agency at the end of October and paid an initial $2,450, then made monthly payments of $1,820 in November, December and January. The final payment was credited back to their bank account, so all told the couple is out more than $6,000.

Thankfully, Trinler said, the couple resisted a pitch by IAC in early January to sign up for a personalized online advertising program -- at an additional cost of $2,400 -- to better market themselves to prospective birth mothers.

According to IAC’s bankruptcy filing, it had total debt of $650,000 and $57,000 in assets.

“I don’t think we will know what really happened or know whether it was well-intentioned bad practice, mismanagement or fraudulent short of state officials doing some type of investigation,” Johnson said.

The CDSS substantiated a 2014 complaint that IAC used improper procedures and had two open investigations into the agency’s conduct when it closed. “If CDSS discovers something unusual, we would cross-report that to the appropriate law enforcement agency,” Weston said.