Adapting to living in isolation

This time of year baby birds not quite ready to fly are stuck in their nests, waiting for their food to be delivered. That's pretty much the way so many of us have felt lately, even as we, too, poke our heads out more and more.

We used to crave silence and solitude; isolation was healing. But chances are most of us would trade peace for other people right about now.

"Human beings do not like to be alone," said Jack Fong, a sociologist at Cal Poly Pomona. "We're not taught to cope in solitude. We're taught to cope with people. We're taught to interact with people to get our validations, and when you're on your own, you have to author your own way out of this. And it's a very scary process."

"And that's really what this is all about, is coping, right?" asked correspondent Lee Cowan. "We're sort of figuring this out every day?"

"It is. It is coping. We need to connect again to the body, to the handshake, to the hug. But for the time being, that's not gonna happen because our physical spaces have been emptied."

And even as they fill up, we're still told to isolate six feet apart.

"Learning how to live in this kind of social straitjacket is kind of a new thing for us," said Steve Cole, a genomics researcher at UCLA. He said loneliness isn't just a mental deficit; it can be a physical one, too. "We're literally more likely to die, more likely to get cancer, more likely to get heart attacks, more likely to get Alzheimer's disease, and more vulnerable to viral infections, when we're lonely."

Blame what he calls our "dinosaur brain." Long ago, being alone meant being an easy lunch for something bigger and more powerful.

Our brains are wired, Cole said, to see isolation as a threat. "What happens, when we feel lonely, is that dinosaur brain immediately computes, 'Not safe.' And it triggers these physiological responses that get us ready for injury, completely, without us thinking about it. So we may not even be aware of this."

Cowan asked, "So even just being alone for a couple of weeks can have a physiological impact?"

"Absolutely. Even being alone for, you know, a few days is enough to do it."

But isolation doesn't have to get the better of you. Just ask Father Angelus Echeverry, a Benedictine monk at St. Andrews Abbey, on the edge of California's vast Mojave Desert.

"Do you ever get lonely?" Cowan asked.

"Oh sure, sure," Father Angelus replied.

"What would you tell people that are having a hard time with this sort of forced isolation, who haven't chosen this voluntarily, like you? What's your advice to how you get through it?"

"Be gentle with yourself," Father Angelus said. "Be patient. Patience is something that is quite difficult to do, because patience simply means to be able to sit with our suffering. Most of us struggle with that."

But it's in that struggle, he said, that we sometimes forget that while isolation does take, it can also give: "The space has been created for dreaming. The space has been created for allowing our mind to wander."

"You get rid of the clutter?"

"Yeah, yeah," Father Angelus said. "You're not worried about the next thing, because the next thing isn't happening."

History is full of examples of people who have used isolation to their benefit. Henry David Thoreau self-quarantined in the Massachusetts woods for two years, an experiment in what he called "constructive solitude." It gave us his masterwork, "Walden."

In the plague-ridden 1600s, with playhouses closed, William Shakespeare penned "King Lear," "Macbeth" and "Antony and Cleopatra."

Sir Isaac Newton was stuck at home, too, when he developed the theory of gravity.

Newton, Shakespeare and Thoreau however didn't have to worry about home schooling, or job loss, like most of us mere mortals.

But if we can seize on our isolation as an opportunity, like they did, even the smallest thing might empower us to feel a little less alone.

Many of our viewers have sent "Sunday Morning" the ways they have been coping with the lockdown, from sketching, to baking, to quilting.

Carrie Fisher-Pascual has been typing her way out of isolation. "You know, a lot of people are feeling robbed and they're feeling trapped right now," she said. "They're feeling so cut off. But there are certain things that you're never cut off from, you know – your spirit, your hope, your ability to encourage other people."

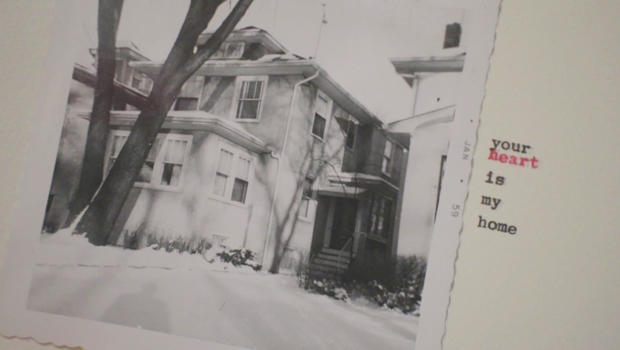

She's making greeting cards using old photographs. She types uplifting captions on them, like "Better Together" or "Your heart is my home."

Fisher-Pascual said, "There's so many challenges. But somewhere in there, there is something that you can be doing. There is a gift in there. And if you can find it, I think that's complete joy."

Nine-year old Alex Nagorny found joy in figuring out how to digitally … disappear. "It's called magic!" he said.

Six-year-old Margot Rocchio discovered nature through a camera lens.

"That's the part I like about this quarantine, but I don't like to not be seeing my friends," she said.

And that, at the end of the day, is really how we all feel. We're all grieving the loss of community, even as we begin to step back out.

Jack Fong said, "I think once we resolve the physiological aspects of this pandemic, we're still gonna have to deal with all the unresolved issues of new fears of the public."

Isolation may linger as long as the virus does. And while it's an unnatural human condition, our experience of being alone could just inspire a new way of living.

"All crises are opportunities to kind of go back to first principles," said Steve Cole, "decide what really matters, readjust our lives, and lead a life that is fundamentally more nutritious for our spirits and souls."

Father Angelus Echeverry said, "Tomorrow's not promised for any of us. And so, what are we doing today? That's the question; how we live today is what will determine tomorrow."

For more info:

- Jack Fong, sociology professor, Cal Poly Pomona, Pomona, Calif.

- Steve Cole, Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, UCLA School of Medicine

- St. Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, Calif.

- Photographer Scot Miller

- Photographer Matthew Ludak

- Photographer Nicole Wolf

Story produced by Jon Carras. Editor: Remington Korper.