A war of words on college campuses

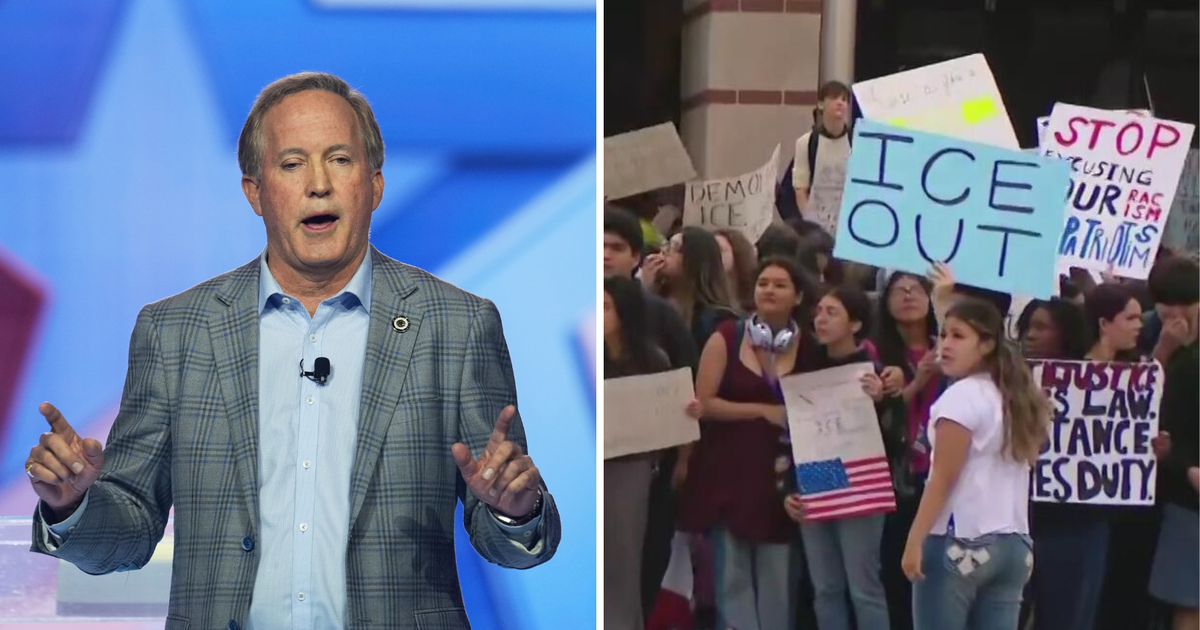

A war of words is raging on many a college campus ... a debate in which the right of free speech itself is under fire. Our Cover Story is reported by Rita Braver:

In the 1960s college students demanded the right to talk about anything on campus, from civil rights to opposing the Vietnam War. All ideas seemed up for debate. But is that still true today?

At Yale University in Connecticut, a faculty member is yelled at by students. The reason? His wife (also a Yale instructor) had suggested students should be free to wear any Halloween costume they choose, even if slightly offensive. A month later, the teacher resigns.

At the University of Missouri, students and faculty try to stop a student reporter from covering their protest. "This is a First Amendment that protects your right to stand here, and protects mine!" the photographer said.

And at the University of California at Berkeley, when conservative commentator Ben Shapiro showed up to speak, there were multiple arrests. The school was on virtual lockdown, and more than half a million dollars was spent on security.

Even comedian Bill Maher faced student calls to cancel his Berkeley commencement address in part because he'd made jokes about Islam.

"Whoever told you, you only had to hear what didn't upset you?" Maher quipped.

But at campuses around the country, some speakers were dis-invited, or simply backed out in the face of student opposition, such as former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, head of the International Monetary Fund Christine Lagarde, and the rapper and actor Common.

It's got a lot of people asking, what is going on?

In September 2015, speaking to young people in Des Moines, Iowa, President Barack Obama said, "I've heard some college campuses where they don't want to have a guest speaker who, you know, is too conservative. Or they don't want to read a book if it has language that is offensive to African Americans. Or somehow sends a demeaning signal towards women … I don't agree with that, that you as students at colleges have to be coddled and protected from different points of view."

Some of the protests are in reaction to deliberately provocative figures, like white nationalist Richard Spencer. But what happens when the speaker says he is just reporting on his academic research?

"I think what I'm saying is important for college kids to hear," said Charles Murray, a libertarian political scientist with the American Enterprise Institute. His 2012 book "Coming Apart" explores the growing divide between rich and poor white Americans.

"Most of my lectures are going after them as members of a new elite that [is] out of touch with mainstream America," Murray said.

But when he came to talk about it at Middlebury College in Vermont last March, there were protests, as chanting and yelling students shouted him down.

Phil Hoxie, a member of the student wing of the American Enterprise Institute, helped bring Murray to campus. He told Braver he knew that Murray would be controversial: "It wasn't a surprise to us that some people might not like 'The Bell Curve.' But we were not at all hoping that he would discuss 'The Bell Curve.' We were hoping that he would give a lecture on 'Coming Apart.'"

"The Bell Curve" is a previous book of Murray's which suggested race may play a part in determining intelligence, and asserted that blacks do less well than whites on IQ tests. That set off a firestorm when it was published in 1994 … a firestorm reignited at Middlebury.

"The speakers the college invites play a key role in our mission as a college," said senior Jeremy Alben. "And I don't think Murray's scholarship should be part of the academic mission."

Sophomore Rae Aaron was hoping to ask Murray some tough questions: "It's very ironic that the students who claim to be the most liberal are the ones who are not willing to engage with controversial ideas," she said. "At some point, it turned into, not an argument of, 'We should protest his ideas,' but 'We should protest his right to share his ideas.'"

Murray was set to be interviewed by political science professor Allison Stanger. But seconds after they took the stage, students drowned them out with a tirade of shouts. "We really lost an education opportunity," Stanger told Braver.

"We didn't actually prevent him from speaking," said student Liz Dunn. "He still wrote plenty of articles before and after the talk. It was just saying in this specific time on this specific stage, we're sending you a message that we do not support your ideals."

Students like Dunn and Alben insist that just letting someone like Murray be heard increases the likelihood of violence against minorities.

"If you want to engage with this scholar and you believe that your right to see them and engage with them is so strong that you don't care about the potential trauma or the potential violence this could bring to marginalized students, then I think it's a pretty selfish idea of academic engagement," Alben said.

In fact, Murray's appearance did result in violence, of a different kind. When professor Stanger was escorting Murray out, they were attacked by a mob that included outside activists, and she was left with a concussion and whiplash.

Ironically, Stanger was selected to moderate the event because she was seen as a respected professor with liberal credentials.

"I actually went back and reviewed 'The Bell Curve' and prepared really tough questions that I never really got to ask in front of an audience that was listening," she told Braver. "It was this real group-think mob mentality where people weren't reading and thinking for themselves, but rather relying on other people to tell them what to think."

And it isn't just Middlebury; Murray was shouted down at the University of Michigan this past fall as well.

Braver asked, "What do you think is different [on college campuses]? Have students changed?"

"Well, the identity politics is way more intense," Murray replied. "You are getting this, 'You can't talk to me about any of my life experiences because you aren't a woman, and you aren't Black, or you aren't poor,' and therefore it's almost as if they're saying we have no common humanity."

In fact, some critics say too many college campuses today aren't places for a civil exchange of ideas, but an intolerant world of political correctness.

A recent Gallup poll finds that 54% of college students say people on campus are afraid to say what they believe.

- Free Expression on Campus: A Survey of U.S. College Students and U.S. Adults, Knight Foundation/Newseum Institute (pdf)

And if you visit a campus these days, you may feel like you need a dictionary for a whole new set of phrases … terms like "safe space" (a place where students can go where they won't be exposed to topics that make them uncomfortable), or "trigger warnings" (when a professor cautions students that upcoming material could be distressing).

But now, some signs of a backlash.

Robert Zimmer, president of the University of Chicago, told Braver, "Discomfort is an intrinsic part of an education."

Last school year, the university sent a letter to incoming freshman that said, in part:

"[W]e do not support so-called 'trigger warnings,' we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual 'safe spaces' where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own…"

Braver asked, "Why did the university have to put out a letter like that in the first place?"

"Part of the way we operate is that we're a place where there's constant open discourse, constant expression and constant argument," Zimmer replied.

But the war of words is continuing on college campuses across the country, including Middlebury, where students like Liz Dunn and Rae Aaron say the impact of the Charles Murray incident is still being felt.

Braver asked, "Why is this a good thing in your mind that these protests are going forward?"

Dunn replied, "I think that it's always a good thing to realize that we are actually able to challenge authority and that we actually have a voice and a place and the ability to express that, and that what we're experiencing is important and is something that we can change."

"In the end, I think the conversation turned into whether or not we support controversial ideas," Aaron said. "And, for me, it's hands down, of course we do. It doesn't matter how much we disagree with them."

For more info:

- Charles Murray, American Enterprise Institute

- "Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010" by Charles Murray (Crown Forum), in Hardcover, Trade Paperback and eBook Formats; Available via Amazon

- Allison Stanger, Middlebury College

- Robert Zimmer, president, University of Chicago