A sense of direction: Finding your way without GPS

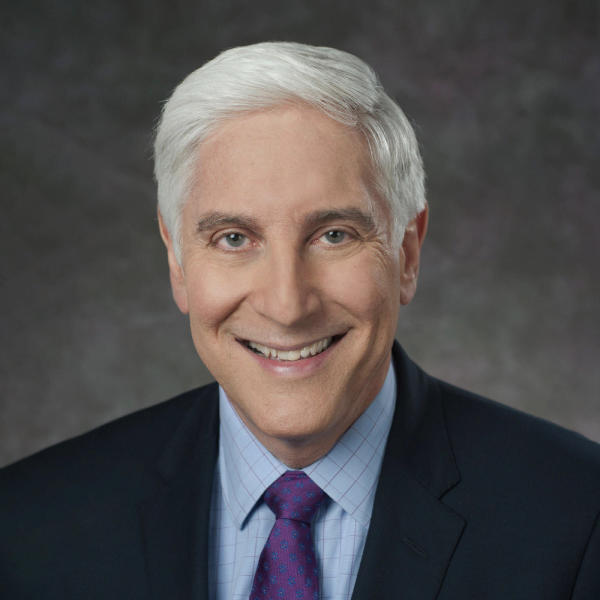

By CBS News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jon LaPook.

There's one thing all animals have in common: a sense of direction. And while other animals may navigate better than we humans, most humans navigate better than I do.

Case in point: The time I visited Iceland with my son. On our first day in Reykjavík, on the main drag where our hotel is, with the Atlantic Ocean over there, I got completely turned around – didn't know where our hotel is.

That's why I need help.

Despite my trouble with navigation, I did manage to track down some experts in the field. We started with Vermont Game Warden Mark Schichtle, who taught other game wardens some tricks of the trade.

Official term: land navigation skills.

"Whenever I'm introducing somebody to navigating in the wilderness, I teach 'em to do a 'Crazy Ivan,'" Schichtle said.

It's a "Hunt for Red October" reference, describing how a Russian submarine captain will sometimes turn suddenly to see if there's anyone behind them.

"Same thing applies to here," Schichtle said. "As you're walking, just periodically turn around and look to see what the return trip looks like."

Part of it, for somebody like me who lives in the city, is to train yourself to notice, "Oh, there's some orange clump of berries there," as opposed to just saying, "Oh, it's a … bunch of wilderness."

Either way, humans have one advantage over other animals: The ability to use symbols and tools, like a compass and maps.

Once pointed in the right direction, the next task is staying on course by orienting the compass and map, picking a target, and then heading for it. Repeat until you reach your destination.

Schichtle said, "Orienting yourself on the surface of the Earth is a skill that human beings have; I think all of us have that to a greater or lesser degree."

Professor Nora Newcombe, of Temple University, studies the psychology of sense of direction. "All of our senses are involved together in forming this sense of place," she said.

What got her interested in sense of direction? "Basically, that people are bad at it!" she said. "And yet, they ought to be good at it, because if you lose your way, that's really a threat to survival."

A sense of direction is encoded in the very wiring of the brain. Specialized cells track where you're headed and where you are in relation to landmarks – a kind of internal map system.

In 2014 the Nobel Prize was awarded to the scientists who discovered place cells (which pinpoint particular locations to help us recognize our environment) and grid cells (that make a grid-like pattern to help track distance and position).

"These are cells that fire when you're at this place, but also this place or this place or this place or this place in a regular grid-like pattern," Newcombe said.

Which means, your brain is actually creating maps of where you've been.

LaPook asked, "In your research, have you found that men ask for directions more or less than women?"

"Actually, people don't exactly know that!" Newcombe laughed.

Research has shown some differences: men can escape from a maze faster than females, and might be more likely to take shortcuts.

"There are definitely biological theories," said Newcombe. "People make it out to be a really big difference. But it's not that big."

"In my marriage, my wife usually drives," LaPook said. "And she does have a better sense of direction than I do."

"Yeah, well, in my marriage I'm the one who says, 'Let's not ask for directions, let's use the map,' so we both defy sex stereotypes!"

Newcombe showed us how she uses a virtual world to test people on learning, remembering, and connecting routes. "We're trying to diagnose a sense of direction, and some people turn out to be much better at this than others," she said.

She's building a cognitive profile of proficient human navigators.

"So, what this is really testing is your ability to figure out where something is without seeing it?" asked LaPook. "What do you learn from something like this?"

Newcombe said, "Some people are pretty good at putting together a route, and then some of the people who can put together the route are good at relating the routes to each other. But some people are truly extraordinary."

"How do you explain that sense-of-direction savant?"

"They are using – sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously – every single cue there is, and really from the start trying to make that sort of overhead map."

"Do I clearly fall into a group yet?"

Newcombe said, "I would say, not what we call an imprecise navigator. So, you passed that bar."

So, not great, but I'm not imprecise!

Of course, in today's cellphone world, imprecise human navigators can survive. But for animals, it's a different story. If, say, a migrating bird doesn't pay attention to where it is going, it will not be very successful.

Robert "Rocky" Rockwell, a biologist at New York's American Museum of Natural History, studies polar bears and snow geese in the Canadian Arctic. "I move north with the birds, literally," he said.

He migrates? "Every spring!" And he has for 51 years.

His birds spend the winter along the Gulf Coast, and migrate north to the Arctic tundra. Then, as they move along, they use visual cues to find places that have got agricultural fields, and rivers that they recognize – stops which fuel their 2,500-mile flight

"When they get right to the nesting colony, the female snow goose will oftentimes nest within two feet of where she nested last year," Rockwell said. "I think it's a combination of cues."

Beyond visual cues, the birds use the position of the sun, a sense of smell, and a kind of built-in compass. They may also possess a magnetic sense. "As you get closer and closer to the poles, the magnetic strength is a little higher," Rockwell said.

"And they can feel it?" LaPook asked.

"It is thought that they can do that."

"Is there anything about this as you study it that you thought, 'This is magic'?"

"I think the magic is that, they can use all these sensory modalities and integrate them flawlessly," he replied.

The experts agreed: it's possible to hone a sense of direction, but awareness is key.

Schichtle asked, "As someone who arrived this morning saying, 'I have absolutely no sense of direction,' how do you feel now? A little bit better?"

"I do feel better," LaPook replied. "Seriously, I mean, it's exciting to learn how to use even just a compass in conjunction with a map, for real."

But in terms of a sense of direction, what can we learn from other animals?

According to Rockwell, "I think the best thing we can learn from them is watch how they deal with their environment. An elder told me when I first started working in the Arctic that I should just sit on a rock and watch the animals. The point is to be aware of what's going on around you. And I think too many of us get fixated on, 'Well, I can always find my way because I can pull out Google Maps, or I can pull out my phone and tell it I wanna go there and then just follow the little arrow.'"

LaPook asked Newcombe, "So, where does GPS come in here? Is it bad for our sense of direction?"

"Lots of people do think that it's bad, including me," she replied. "If you rely on it too much, then you aren't forming an overview of the environment. You're preventing yourself from building up something that I strongly feel is part of appreciating the world."

Which is to say, instead of looking down at your phone, look around, because to get where you're going, you've got to really see where you are.

For more info:

- Nora Newcombe, Temple University

- Robert "Rocky" Rockwell, American Museum of Natural History

- Footage from Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Story produced by Amy Birnbaum. Editor: Heather Spinelli.