A place at the table

The hungry and homeless of Philadelphia can always find a place at the table, thanks to a pair of restaurateurs with big hearts and hard-earned personal experience. Nancy Giles serves up their story:

Something unusual is happening in the City of Brotherly Love. A new restaurant called Rooster Soup Company opened earlier this year, and it has a lot to crow about already. It's been named one of America's "top ten new restaurants" by both Food & Wine and GQ magazines.

Rooster Soup is also doing well in another way -- it gives away every penny of its profits.

Giles said, "Someone might say that you guys are just doing this for good press."

"I think that there are probably easier ways to get press," said chef Mike Solomonov. "Opening a restaurant with 100% of the profit going to somebody else is, like, a crazy thing."

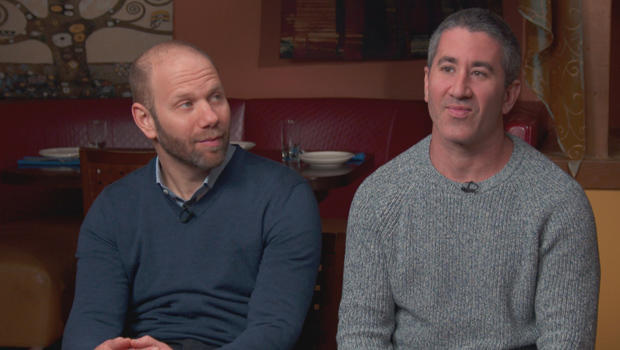

Solomonov and his business partner, Steve Cook, run Rooster Soup and a small empire of restaurants in Philadelphia. Their kind of crazy fit right in with the radical mission of Broad Street Ministry, located in a 100-year-old Presbyterian church in the heart of Philadelphia, where all that money is going.

"We like to say that we exercise radical hospitality," said Mike Dahl, the executive director of Broad Street Ministry.

What does that mean? "For me, radical hospitality means that in this space, everyone is welcome just the way they are."

In one of the poorest big cities in America, Broad Street has delivered "radical hospitality" to thousands of Philly's most needy since 2008, by providing shelter when it's cold, and hot meals for the hungry.

"Seven times a week, we open our doors to the most vulnerable populations in Philadelphia," he told Giles. "And we welcome them in, and provide them with a warm and nutritious meal. And it's served at the table with linen and with china by volunteers who are gonna treat the guests just like you'd want to be treated -- with dignity, with respect, with care."

The "guests," as they're called at Broad Street, may be homeless, drug-addicted, or just lonely. It doesn't matter.

"No judgment," said one guest named Deborah. "Like they say. 'If you're here, you belong here.' They got a sign outside"

Another guest, John Khalil Moody, said, "They don't care how bad you look, how bad you smell. Everybody gets treated the same."

"You don't feel like you're going to a soup kitchen," said James Tarone. "You almost feel like you're going to a restaurant. They serve you. The food is absolutely outstanding. Their services here are ridiculously good."

"Ridiculously good service"? That may be because many of the waiters and waitresses doing the serving are professionals, so inspired by Broad Street's radical hospitality that they're working for free.

Just like Rooster Soup's Steve Cook did, when he first volunteered at Broad Street four years ago, and got inspired himself.

"And so I came back pretty charged up from that first experience,' Cook said, "and Mike and I talked about it. I said, 'We really ought to bring our staff here.'"

Charging up the staff wasn't very hard -- the crew at Zahav, Solomonov and Cook's four-star Israeli-American restaurant, often start their shift with dancing and splits. And when he's not doing splits, Solomonov mans the oven, making all the bread, including laffa, an Iraqi-style pita.

Solomonov's laffa bread and hummus, and the rest of his menu, have earned him four prestigious James Beard Awards. He was named "Outstanding Chef in America" just this May.

The restaurant is an amazing success. But it could have very easily gone a different way. As Solomonov has said, "Nobody expects someone like me to be a recovering crackhead."

He explained: "After my younger brother was killed in action in the Israeli military, the way that I coped with it -- or thought I was coping -- was to use and abuse substances."

Solomonov was using not just crack, but heroin, when Cook found out about it back in 2008, Zahav's first year of business.

"So it was a really difficult year," Solomonov said. "I leaned on Steve tremendously. Steve, I feel like, is at this point a drug counselor. And the first thing that Steve said was that, 'We know that you have a problem. And we wanna help you. And we wanna take you to detox.'"

"Some of the people that are benefiting from Broad Street aren't as lucky as you were," Giles said.

"There are people that are just like me, right? That didn't have support, that are now living on the street. And unfortunately, none of us are really immune to that."

These two give Philly's "brotherly love" nickname some real meaning.

"The first week that we were open, Steve cut a check to Broad Street Ministry which was probably enough to serve hundreds of people," Solomonov said. "So it's that sort of tangible."

And all that money they're raising at Rooster Soup is changing lives at Broad Street.

"They basically saved my life," said Tarone. "Like, for real. I was thinking of just ending it."

Mike Dahl said, "I've had so many times where people have said, you know, 'This place saved my life.' Look, we're so grateful for the money that's gonna come across to help our mission. But I think the promise of Rooster Soup is so much more than that."

"It's a model -- I feel like that should be all over the country," said Giles.

"That would be a great thing," Dahl said.

For more info:

- Rooster Soup Co., Philadelphia

- Broad Street Hospitality Collaborative, Philadelphia | Donate