9/11 through a child's eyes: Survivor overcomes PTSD, addiction

“Where were you on the morning of 9/11?” It’s a question most everyone has been asked. Helaina Hovitz was attending her second day of class at I.S. 89, a middle school just three blocks away from the World Trade Center in lower Manhattan. She was 12 years old and in seventh grade at the time of the attacks.

The horrific events that millions of people saw on television happened right before her eyes. The sickening thuds of falling bodies hitting the concrete, the towers collapsing, running for her life in a cloud of dust and debris – these are forever engrained in Hovitz’s memory.

Yet, while she came out of that day physically unharmed, like most survivors of such traumatic events, the nightmare was far from over.

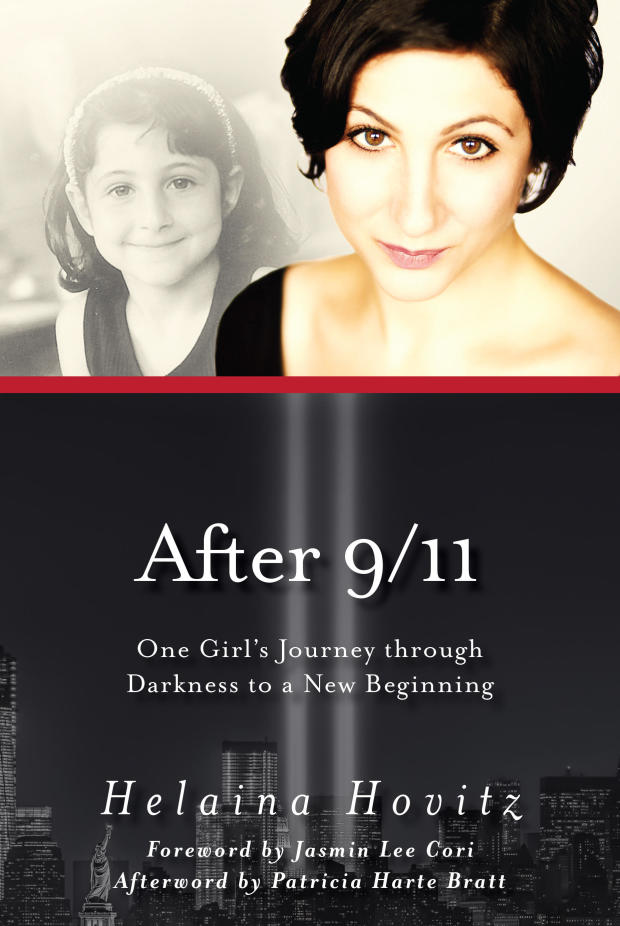

This week, just days before the 15th anniversary of the September 11th terrorist attacks, Hovitz released a memoir entitled “After 9/11: One Girl’s Journey Through Darkness to a New Beginning.”

In the book, she recounts the all-too familiar events of the day as seen through a child’s eyes. She also details her struggle through more than a decade of misdiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the alcoholism that came with it, and she writes about what finally helped her cope.

CBS News spoke with Hovitz, as well as her current therapist Jennifer Hartstein, to discuss the often untold story of the lasting impact the events of 9/11 had on the children who were there.

“Run for your life”

Hovitz remembers sitting in her first-period class when what sounded like a giant whirring motor interrupted her teacher. It was the sound of the first plane crashing into the North Tower.

Amid the terror and confusion that ensued, a bomb squad burst into the school and told everyone they needed to evacuate.

Hovitz connected with a neighbor she usually walked home with, but their normal route was blocked by smoke, ash, and police barricades.

“We were a few blocks away when all of a sudden we heard this noise and we heard people scream ‘run for your lives,’” Hovitz told CBS News.

The first tower was collapsing behind her, and she ran, passing people bleeding, wheezing and screaming – many covered in white and red – along the way.

“I thought the world was ending. Period. I literally thought that was it,” Hovitz said.

Eventually, she made it home to her family. That night, without electricity and much of their home covered in ash and soot, they slept in total darkness except for the eerie glow coming from the fire at what was now being referred to as Ground Zero.

Trying to “go back to normal”

The days following the attacks were terrifying for Hovitz. If a plane flew overhead, she immediately thought a bomb was going to fall and she was going to die.

A couple of weeks later, she returned to school, though she and her classmates were relocated to a different building further uptown.

At the time, New York City was trying to “go back to normal,” but for Hovitz and so many others affected, that would be nearly impossible.

She began having trouble at school. New classmates bullied her because of her severe, panicked reactions to loud noises – a telltale symptom of PTSD. By the end of the school year, isolation set in and Hovitz was anxious, sad, and constantly on edge.

When she began high school, it did not bring her the fresh start she had hoped for. She turned to alcohol to help her feel better – but that temporary respite only deepened her problems.

She continued to have flashbacks and panicked every time the subway stopped in the middle of the tunnel, fearing her life was about to end at the hands of another attack.

Over the next several years, Hovitz saw a number of therapists and was diagnosed with a range of conditions: depression, attention deficit disorder, and bipolar disorder. After the different misdiagnoses, she was treated with a variety of medications – most of which only exacerbated her symptoms instead of making them better.

Her panic attacks and sleepless nights continued, and her addiction to alcohol worsened. She even considered suicide. That’s when she decided to try therapy one more time.

She met Dr. Jennifer Hartstein, who was the first doctor to tell her that she had PTSD. For Hovitz, upon hearing that and learning more about the disorder, it all finally started to make sense.

“It was almost like, ‘oh, of course.’ That understanding that after all that time that there was a name for it and there was a way [to get better], it was just like validating everything that I went through. It was definitely a relief.”

Now she could begin the long process of putting her life back together.

A shared struggle

At one point during her recovery, Hovitz reached out to some of her former classmates and learned many had similar experiences. In her book, she recounts some of the things they told her:

“I thought I’d never be normal like my friends.”

“I cut myself. I banged my head against a wall.”

“What seemed like a small problem to others felt like a tragedy to me.”

“I felt branded, wounded, damaged, and crazy.”

“Getting upset was never just getting upset – it lasted for hours, days, and months.”

Hartstein said that while no two children cope the same way, it’s likely that many of those who were there during the attacks on 9/11 suffered some mental trauma.

“It would not be surprising for many of them to have struggled with some PTSD symptoms over the course of their development, especially some depressive or anxious symptoms,” she told CBS News. “It is hard to imagine that the young people who lived that close to the tragedy would not have some psychological reaction to it, although it is not a given that all do.”

“The last piece of the puzzle”

Hovitz and Hartsein worked together on cognitive behavioral treatments that helped her cope with her condition.

But the true path toward recovery began when she decided she needed to beat her alcohol addiction. Hovitz entered a 12-step program and never drank alcohol again. This November, she will be five years sober.

“That was really the last piece of the puzzle because that was learning to experience all these things that were difficult, painful, and uncomfortable and now there was no escaping it,” she said.

Along with the techniques she learned from Hartstein, Hovitz also took up yoga and meditation.

She no longer panics when the subway stops suddenly, and she is able to concentrate on the present moment.

While she continues to see Hartsein to help monitor her progress, Hovitz says it’s amazing how far she’s come.

“I was fortunate enough to be able to come out on the other side. That’s why I’ve been able to write this book,” she said. “I’ve had to work so hard for it, but I learned to become a woman who could sit in a room with herself and watch TV or read a book and not have it feel like torture but to have it feel actually nice. This person I thought I could never be which was just calm and happy and giving and all these things that there was just no room for because I hadn’t had time to develop an identity… I’ve been able to become.”