7 reasons to avoid commodities and why they're wrong

(MoneyWatch) One of the most contentious debates in finance is whether investors should consider including an allocation to commodities in their portfolio. The reason for considering including commodities is that they act as a form of portfolio insurance. Commodities have been shown to hedge the risks of unexpected inflation, tending to perform best during periods of rising inflation, when nominal return bonds do poorly. Commodities also have been shown to hedge supply shocks that hurt stock returns (such as the oil embargo of 1973-74), though not demand shocks to the economy (such as the financial crisis of 2008). And historically, including commodities has led to more efficient portfolios (higher risk-adjusted returns).

Yet, there are many critics who claim a host of reasons to avoid commodities. Today, we'll address the seven most often cited reasons to not include them in your portfolio. In our analysis, we'll show the data for the two major commodities indexes, the S&P GSCI and the DJ-UBS. The major differences between the indexes are time frame (with the S&P GSCI starting in 1970 and the DJ-UBS starting in 1991) and make-up (with the DJ-UBS being less concentrated in energy).

High volatility

Many claim that commodities are too volatile to effectively hedge inflation. Before we review the data, keep the following in mind: Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS) are the best hedge against inflation. The monthly volatility of the TIPS Index is about four times that of the CPI. This means TIPS may be too volatile if your investment horizon is very short, but not otherwise. The same is true for commodities.

For the S&P GSCI, the monthly standard deviation was 5.76, or almost 16 times the 0.37 volatility of the CPI, giving credence to the claim that it's too volatile. It's a similar story for the quarterly and annual standard deviation and for the DJ-UBS as well.

However, the way to determine if something acts as a hedge is to examine their correlation. If commodities don't provide any inflation hedge, their correlation with inflation should be close to zero. Again, before looking at the data keep in mind that the monthly, quarterly and annual correlation of the TIPS Index (inception 1997) to inflation has been about 0.1, 0.2 and 0.5, respectively.

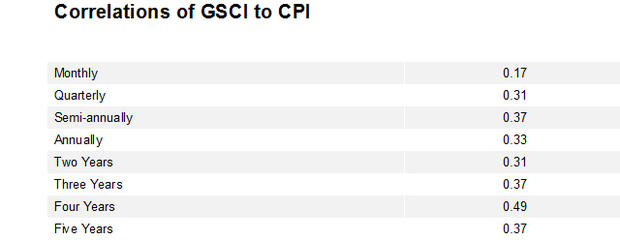

While the monthly correlation of the GSCI to the CPI has been fairly low at 0.17, as we extend the horizon the correlation tends to increase, as the table below demonstrates.

Thus, we see that as we extend our horizon an important component of the return on commodities is explained by the inflation rate.

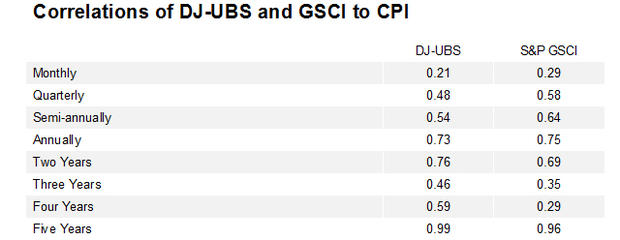

Let's take a look at the correlation data on the DJ-UBS index and the CPI (available from February 1991). Since we have the data for the GSCI for the same period, we'll show that as well.

While the period is shorter and thus less reliable, we do see a strong tendency for the correlations to rise as the horizon lengthens. We can conclude that while commodities don't perfectly hedge against inflation, they do have some value as an inflation hedge.

Finally, it's worth adding that commodities have performed best during the few periods of rising inflation that we have experienced since 1970. In other words, they performed best when their hedging value was needed most.

Low expected returns

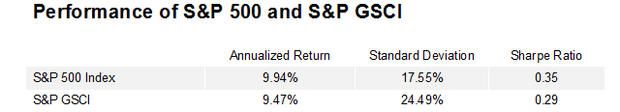

The longest data series we have for commodities is the S&P GSCI. The table below shows the returns data.

Rightfully, critics of commodities point out that the similarity in returns shouldn't have been expected. If we break the full period into two parts, we see that it was the outstanding returns from 1970-1990 that explain the full period's outcome. During this 21-year period, the S&P GSCI returned 16.50 percent, the S&P 500 returned 11.16 percent and inflation averaged 6.22 percent. Thus, commodities performed well during a period when inflation was more than twice its long-term average.

While you might expect stocks to return about 5 percent above inflation, as they did during this period, commodities shouldn't be expected to return more than 10 percent above inflation. Because commodities aren't a real asset, it's reasonable to expect that they will rise in line with inflation over the long term. This was basically what occurred in the ensuing period.

From 1991 through 2012, the story was quite different -- the S&P 500 returned 9.11 percent, the S&P GSCI returned 3.21 percent and inflation rose 2.50 percent per year. Critics point out that commodities shouldn't play a role in the portfolio given the low expected return.

We agree that the last 22 years provided the type of relative returns one should expect from commodities. In fact, any asset (such as commodities) that provides a form of portfolio insurance should have low expected returns. However, the expected returns shouldn't be the only consideration. That makes the mistake of thinking about assets in isolation. The only right way to think about them is this: How does the addition of the asset impact both the risk and return of the entire portfolio? As the data in the tables below demonstrate, commodities have provided a diversification benefit due to their very low to negative correlations with both stocks and bonds.

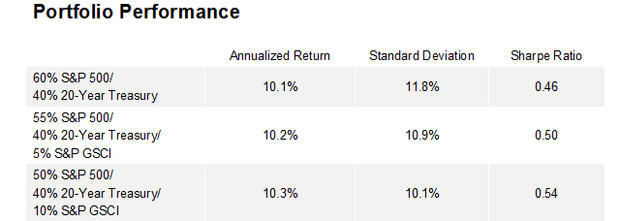

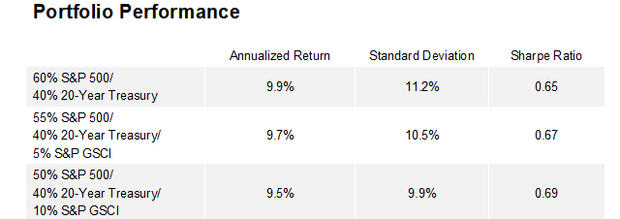

Critics rightly point out that the data above shouldn't be relied on because in the first 21years, commodity returns were well above what we should expect. So let's look at the impact that adding commodities had during the last 22 years when they provided returns relatively in line with expectations.

As you can see, the addition of commodities created a more efficient portfolio. While the portfolio with commodities experienced a lower return, the volatility was reduced by an even greater amount. And this was during a period when the hedging benefits of commodities weren't needed -- inflation was only 2.5 percent a year, and there were no supply shocks like we experienced in the 1970s. In other words, adding commodities gave you portfolio insurance, and yet you still had a more efficient portfolio, making the insurance basically free.

The bottom line is that adding commodities to a portfolio doesn't require a belief in high returns. It only requires a belief in the diversification benefits.

Already exposed

Another common refrain against commodities is that you're already exposed to these assets through a diversified stock portfolio, which would include the stocks of commodity producers. While this criticism is true, it makes the mistake of not seeing the whole picture. While a broadly diversified stock portfolio does provide exposure to commodity producers (such as energy and mining companies), it also provides exposure to commodity consumers, which are hurt by rising prices. In addition, rising commodity prices negatively impact consumption in the same way that a tax increase does, and that has negative implications for stocks. A third problem is that many commodity producers hedge at least some of their production by selling it forward in the futures market.

A simple test to see if the criticism holds water is to look at the correlation of returns. If a diversified portfolio provided net exposure to commodities, we would see a strong positive correlation between commodities and stocks. From 1970 through 2012 the annual correlation of the S&P 500 and the S&P GSCI was actually slightly negative at -0.063. Clearly, owning a broadly diversified stock portfolio doesn't provide you with net exposure to commodities.

High trading costs

While strategies don't have costs, implementing them does. Critics point out that the index returns overstate the benefits of commodities because they don't contain the costs a live fund would incur. Those costs include not only the fund's expense ratio, but also the costs of trading. And by their nature commodities funds tend to have relatively high turnover. To see if this criticism holds up, we'll take a look at the returns of two mutual funds that have a passive approach to commodities exposure: Dimensional Fund Advisors' Commodities Strategy Portfolio (DCMSX) and PIMCO's Commodity Real Return Strategy Fund (PCRIX).

DCMSX has an expense ratio of 0.35 percent. From inception in December 2010 through May 2013, the fund's annualized return was -3.1 percent, beating the -4.5 percent return of its benchmark, the DJ-UBS index. (However, it did lag the 0.8 percent return of the S&P GSCI.) Even though the index has no expenses while the fund does (including transactions costs), the fund outperformed its benchmark, the DJ-UBS Commodities Index by a total of 3.2 percent (-7.6 percent versus -10.8 percent). (Disclosure: My firm, Buckingham Asset Management, primarily uses DFA funds in constructing client portfolios.)

We now turn to PCRIX, which has a much higher hurdle to overcome than does DFA's fund as its expense ratio is 0.74 percent. From inception in July 2002 through May 2013, the fund returned 8.3 percent per year, while the S&P GSCI returned 3.3 percent per year and the DJ-UBS returned 4.2 percent per year.

The evidence seems clear that a well-designed fund can at least replicate the returns of its benchmark, even after expenses. (See my prior post available describing how passive commodity funds can beat their indexes.)

Not a perfect hedge

In 2008, when the S&P 500 lost 37 percent, the S&P GSCI fell an even greater 46.5 percent. This led many investors and commentators to wonder what went wrong? Weren't commodities supposed to be an effective hedge of stock risks?

Those who drew that conclusion not only didn't understand the nature of commodities, but they didn't know their financial history. It's not just that we experienced a bear market, but it's the type of bear market we experienced that makes a difference.

There are basically two different kinds of shocks to our economic system and stocks. Supply shocks are the result of events like wars, political instability and extreme weather. These events usually push commodity prices higher while typically causing stocks to drop. Demand shocks occur when events cause demand to fall. (An example would be when the Federal Reserve drove real interest rates up to fight inflation in 1981.) These are bad for both commodities and stocks.

Investors who knew their history understood that another demand shock would likely cause the correlation of returns for stocks and commodities to rise, and both commodities and stocks would perform poorly. This relationship is why any allocation to commodities should be taken from the stock allocation. Doing so reduces the volatility of the portfolio. Taking the allocation from the bond side would increase it.

For commodities to truly act as portfolio insurance, which is the only real reason to invest in them, you have to consider all three asset classes -- stocks, commodities and longer-term Treasury bonds -- in your portfolio. While it's possible, we have never experienced a period when all three assets have produced negative returns. Therefore, if you include some exposure to commodities in your portfolio, you can also consider taking more duration risk with your high-quality bonds and earn the incremental term premium that is typically present.

The reason is that commodities and longer-term Treasuries hedge the other's risks. Commodities do poorly in deflationary periods, but longer-term Treasuries do well. In inflationary periods, the reverse is true. The table below presents the evidence from the three periods when we experienced demand shocks.

The bottom line is that commodities can't be seen as a perfect portfolio hedge. However, they still offer protection against some major events. They tend to perform best in periods of rising inflation and during periods of supply shocks. They simply don't perform well when we experience demand shocks like we had in 1981, 2001 and 2008.

Contango

As commodities gained popularity for diversifying a portfolio, there was a surge in demand for commodity futures contracts by investors. Observers of this trend noted that it was accompanied by years of what is known as contango in the markets for oil contracts. (Contango occurs when the future price of a commodity is higher than the current price.)

When contango exists, commodity futures funds have to sell contracts at low near-month prices and buy more costly further-month contracts. Along with the costs of running a fund, persistent contango can cause the returns of a fund to trail the returns of spot prices by large amounts.

Thus, the argument that was heard against investing in commodities futures was that the demand from hedgers permanently doomed the markets to a state of large contango. And that seemed to be the case for quite a while. As investor demand soared, assets in commodity funds rose sharply, and the contango in the oil market reached high levels.

However, while the hedging demand from investors doesn't seem to have slackened much, the size of the contango has been coming down this year. For months now, the near-month contracts have basically been trading at about the same level as the spot rate, but the further out contracts have been trading in significant backwardation (the opposite of contango, or when the future price is lower than the current price). For example, on June 17 the July 2013 oil contract closed at 97.85, the December 2014 contract closed at 90.85, a 7 percent discount. While commodity indexes always use the near month, a fund can choose which month's contracts to buy.

Commodities are no different than other investments. High costs will eventually drive down demand, and costs (future prices) will fall, and vice versa. Thus, persistent large contango isn't any more likely a condition than persistent large backwardation (which would bring increased demand and rising prices).

Overstated benefits

Another argument is that commodities can't have the same Sharpe ratio as stocks, be negatively correlated to both stocks and bonds, and be a good hedge against inflation all at the same time. We agree with this statement. However, it also misses the point.

There are simple and logical economic reasons to expect commodities to have low to negative correlation with both stocks and bonds. As we have shown, commodities are also positively correlated with inflation at relevant horizons. However, commodities shouldn't have the same expected Sharpe ratio as stocks. In fact, we expect it to be much lower.

From 1991 through 2012 the S&P 500 returned 9.11 percent and the S&P GSCI returned 3.21. During this period, the Sharpe ratio was 0.41 for stocks and 0.13 for the S&P GSCI. Yet, even during this period, the inclusion of commodities improved the efficiency of the portfolio. And given the evidence on live funds being able to outperform their benchmark index after costs, the historical data might be understating the benefits of including commodities.

The bottom line is that while this "criticism" is correct, it's irrelevant because it makes the mistake of thinking of commodities in isolation when the only right way to think about them is how their addition impacts the risks and return of the overall portfolio.

The weight of the evidence suggests that the criticisms against considering an allocation to commodities in your portfolio don't hold up to scrutiny. The evidence presented here should also make clear that it's important to never make an investment without fully understanding the risks and expected returns as well as how the risks of that particular investment mix with the risks of the rest of the portfolio.