Rikers Island

The following is a script from "Rikers Island" which aired on April 17, 2016. Bill Whitaker is the correspondent. Deirdre Cohen and Sarah Koch, producers.

There has been a lot of talk about criminal justice reform in America and it would be hard to find a place more in need of reform than Rikers Island, the most important jail in New York City.

Located in the middle of the East River, Rikers holds about 10,000 inmates. It's a volatile mix. Some have been convicted of minor crimes; but as many as 80 percent are awaiting trial. Many are there because they can't make bail. And, in a trend that reflects a growing national problem, Rikers holds a rising number of mentally ill inmates. The mentally ill now make up more than 40 percent of the population.

Correction officers are not adequately trained to deal with this population. The result is a disturbing pattern of neglect and excessive force that is the focus of our story tonight. It has led the U.S. attorney, Preet Bharara, to intervene.

Preet Bharara: What you really had, we found was-- was a culture of violence on top of a code of silence, and that is a deadly combination. And I mean that literally, as we found in a number of cases that we have brought in connection with Rikers Island.

Concerned by those deaths and a stream of alarming reports about Rikers Island, Preet Bharara who is the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, launched a two-year investigation into the jail complex.

Preet Bharara: We found in an alarming number of cases there was no discipline with respect to officers at all. You had an officer who had dozens of complaints against him and was never disciplined once, or maybe just one time, and that's something that has to change. People have to understand that there are consequences for their actions, not just the inmates, but the officers as well.

Bill Whitaker: How long has this been going on?

Preet Bharara: Years and years. Too long.

Rikers is a 400-acre island just off the tarmac of LaGuardia Airport in the shadows of Manhattan skyscrapers. One bridge leads in and out. It's surrounded by its own moat. The inmate population has come down dramatically from a high of 20,000 to 10,000 but despite the decrease, city data shows violence has gone up over the last decade.

Because of the U.S. attorney's findings, an unusual collaboration was formed. Bharara, the prosecutor, teamed up with plaintiffs' lawyers -- the Legal Aid Society and private attorney Jonathan Abady in a class action lawsuit on behalf of a dozen Rikers inmates.

Jonathan Abady: The number of facial fractures, of traumatic brain injury, of broken bones, of serious physical injury, is just out of control.

Compounding the problems at Rikers is that increase in the number of mentally ill inmates.

Preet Bharara: And that just complicates issues relating to violence and issues relating to care, and issues relating to discipline. So it's a problem.

What was captured on this video, obtained by 60 Minutes, helps illustrate what U.S. Attorney Bharara is talking about. It has not been seen in public before.

Bradley Ballard, who was schizophrenic and diabetic, was brought to Rikers in 2013 on charges of violating parole for an assault conviction. In the video, he was "observed twisting his shirt into a phallic symbol and making a lewd gesture," and then was taken back to his cell, according to an investigation by the New York State Commission of Correction.

Jonathan Abady: He was placed in the functional equivalent of solitary confinement. They put him in a cell. They locked the cell. And they basically threw away the key.

Abady represents Ballard's family in a pending wrongful death suit against the city. The commission's report found that Ballard was locked in his cell for six days prior to his death and was denied access to his life supporting prescription medications and that day after day, officers, supervisors and clinicians walked by, observed his deteriorating state butfailed to help him.

After repeated flooding of Ballard's toilet, a maintenance worker turned off the water running to Ballard's cell. The report found that Ballard was lying in his own waste.

Bill Whitaker: He's spraying-- deodorizer?

Jonathan Abady: Yes. The reports are that corrections officers were bringing aerosol cans from home because the stench was so bad coming from that cell.

Here, an inmate who delivered a food tray pulled his shirt up over his nose. The report found the videotape indicated Ballard's cell was "grossly unsanitary."

Finally, on the sixth day, medical workers were called. According to the report, an officer asked Ballard if he could get up on his own. "I need help," Ballard said. Inmate workers carried him out of his cell and put him on a gurney. Records showed Ballard went into cardiac arrest soon after. He died hours later.

Jonathan Abady: They watched him languish for seven days as he died. And they did nothing. It was the functional equivalent of torture. They killed him.

The city's medical examiner declared Ballard's death a homicide, according to the commission report. It called Ballard's medical and custodial treatment from the time he entered Rikers "so incompetent and inadequate as to shock the conscience." The Department of Correction issued a statement that it "adjusted [its] practices to ensure that a similar tragedy doesn't happen again." But to this day, no criminal charges have been filed against any of the officers, supervisors or health workers involved. It's impossible to know if anyone stepped forward, but if they did, it wasn't enough to help Bradley Ballard.

Norman Seabrook: That's inhumane in my opinion. That should never have happened.

Norman Seabrook is president of the union that represents the correction officers, but not the higher ranking supervisors. We showed him the Ballard video.

Bill Whitaker: Who-- who's-- who's responsible?

Norman Seabrook: The supervisor.

Bill Whitaker: What about your officers?

Norman Seabrook: The officers follow the instructions of the supervisor.

In another incident captured on surveillance video, inmate Jose Bautista tried to hang himself. He had been arrested on domestic charges and was awaiting trial. He couldn't post the $250 bail. When he jumped up suddenly, officers beat him so severely he suffered a perforated bowel and needed emergency surgery, according to case records.

Bautista's case was one of 129 "serious injuries" over an 11-month period documented in a revealing report by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene that was intended for internal use only, but 60 Minutes managed to get a copy. The report found 77 percent of the injuries involved mentally ill inmates and their injuries were severe enough "to require care beyond the capacity of jail medical doctors."

Daniel Selling: You could take a third of the 77 percent and say that, OK, it was the inmate who was just being violent and needed to be subdued. But 77 percent is-- I think tells the story. It's a problem.

Dr. Daniel Selling, who is now in private practice, was the executive director of Mental Health at Rikers for five years until he left in 2014.

Bill Whitaker: Is it fair to say that Rikers is a mental institution?

Daniel Selling: Sure. It's probably one of the largest mental institutions in the nation, if not the largest.

Biill Whitaker: Can you tell me about the case of Bradley Ballard? What does that say about how things work on Rikers?

Daniel Selling: That's probably the worst case - that I've experienced, been a part of. That was a case in which all systems failed.

Selling said the staff of the private medical contractor failed to do the required daily rounds and never informed him about Ballard's deteriorating condition.

The city's contract with the private medical firm was not renewed.

Bradley Ballard is not the only mentally ill inmate to have died in custody in recent years. In 2014, U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara filed the first criminal civil rights case in a decade against a Rikers officer or supervisor in connection with the poisoning of mentally ill inmate Jason Echevarria who died after ingesting toxic soap while in solitary confinement.

As seen in this video that was entered into evidence, Echevarria, a robbery suspect who was also awaiting trial, was escorted to a cell where he swallowed the toxic soap that was given to him for cleaning his cell.

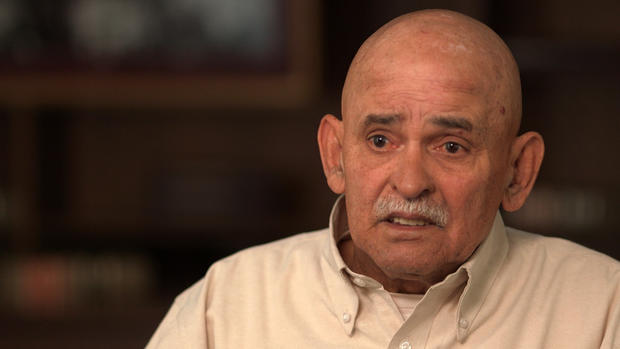

His father Ramon told us he believes he ate the soap in a desperate effort to get out of solitary confinement.

Ramon Echevarria: And my son was screaming 'cause he was burning up inside.

Bill Whitaker: He's dying?

Ramon Echevarria: He's dying.

A few hours later, according to court documents, correction officer Raymond Castro alerted unit supervisor Captain Terrence Pendergrass that Echevarria needed medical attention. According to Castro's testimony, Captain Pendergrass said, "Don't call me if you have live breathing bodies. Only call me if you need a cell extraction or if you have a dead body."

Another correction officer, Angel Lazarte, testified as to what happened next -- a pharmacy technician on her rounds said Echevarria could die. He then approached Pendergrass and Pendergrass told him to write an injury report. You can see on the tape, Pendergrass then went to look into Echevarria's cell himself. He returned and interrupted the writing of the report. Pendergrass led Lazarte away from the desk. After they talked, Lazarte pocketed the report. According to court records, the report was never filed.

Echevarria was discovered dead the next morning. The medical examiner ruled his death a homicide, due to "neglect and denial of medical care."

Ramon Echevarria: He saw him. He was-- he was in pain and everything. Why couldn't you just call an ambulance for him? OK, he's a prisoner, he's an inmate. He's a human being. He's a human being.

Preet Bharara: It both breaks your heart and it makes your blood boil, because you're thinking to yourself, here's somebody who had responsibility for making sure that peace was enforced, but also responsible for the safety and protection of those under his charge.

Bill Whitaker: And that report was never filed.

Preet Bharara: One of the conclusions we found in our investigation was that in case, after case, after case, sometimes you would have individuals who would witness things and they would get together and they would coach each other into what the response should be, which makes it very difficult to hold anyone accountable.

Bill Whitaker: That culture you're describing seemed so entrenched that the officers felt almost comfortable behaving like that even with the cameras running - I'm just what what does that say to you about that culture?

Preet Bharara: Yeah. It says that the culture is broken. It says that the institution is broken.

Captain Pendergrass was convicted in December 2014. A jury found that Pendergrass violated "Jason Echevarria's constitutional rights by deliberately ignoring his pleas for help and depriving him of urgent medical care, leaving Echevarria to die alone in his cell." Pendergrass was sentenced to five years in prison. Officers Castro and Lazarte have since been fired.

Union president Norman Seabrook said his officers don't have the training to deal with mentally ill inmates like Jason Echevarria and Bradley Ballard.

Bill Whitaker: Your men are not trained--

Norman Seabrook: And women. No, they're not trained.

Bill Whitaker: --your men and women are not trained to deal with mental illness?

Norman Seabrook: Not at all.

We asked Norman Seabrook about the internal report showing the vast majority of excessive force cases involving mentally ill inmates.

Norman Seabrook: At the end of the day shouldn't the question be, "Why didn't these individuals receive their medication, so they wouldn't attack a correction officer?" If you're talking about an inmate that has a mental health problem then certainly something set this person off.

Seabrook says it's not just an issue of the mentally ill. Rikers is a dangerous place and many of his officers are assaulted every year.

Seabrook wanted to show us the conditions his officers have to contend with. But when he took us out to Rikers, Department of Correction staffers stopped us from going inside with our cameras to see the problems Seabrook is talking about. This is as far as we got - walking around the perimeter of one of the buildings with him. We wanted to talk to the commissioner of the Corrections Department about the problems at Rikers, but our three scheduled interviews all were postponed.

The city recently initiated a number of policy changes, like installing more cameras and reducing the use of solitary confinement. A federal monitor was appointed to insure the reforms are implemented. U.S. Attorney Bharara is going to hold the city to it.

Bill Whitaker: Is there a decrease in violence?

Preet Bharara: You know, it remains to be seen how much that decrease will be over time. I think the training will take some time and is happening as we speak.

Bill Whitaker: It's taken some time to build up this culture of violence.

Preet Bharara: Yes, it has.

Bill Whitaker: How long do you think it will take to unravel it?

Preet Bharara: I'm not gonna put a clock on it, but I will say that we're-- we're impatient people, and we like to see results, that's why we got involved in the first place.