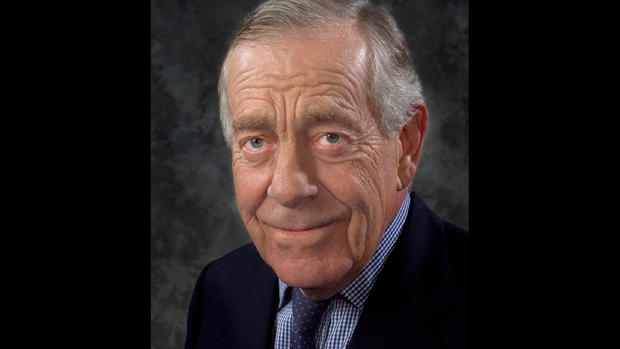

60 Minutes' Morley Safer dies at 84

Morley Safer, the CBS newsman who changed war reporting forever when he showed U.S. Marines burning the huts of Vietnamese villagers and went on to become the iconic 60 Minutes correspondent whose stylish stories on America's most-watched news program made him one of television's most enduring stars, died today in Manhattan. He was 84. He had homes in Manhattan and Chester, Conn.

Safer was in declining health when he announced his retirement last week; CBS News broadcast a long-planned special hour to honor the occasion on Sunday May 15 that he watched in his home.

A huge presence on 60 Minutes for 46 years -- Safer enjoyed the longest run anyone ever had on primetime network television. Though he cut back a decade ago, he still appeared regularly until recently, captivating audiences with his signature stories on art, science and culture. A dashing figure in his checked shirt, polka dot tie and pocket square, Morley Safer -- even his name had panache -- was in his true element playing pool with Jackie Gleason, delivering one of his elegant essays aboard the Orient Express or riffing on Anna Wintour, but he also asked the tough questions and did the big stories. In 2011, over 18.5 million people watched him ask Ruth Madoff how she could not have known her husband Bernard was running a billion-dollar Ponzi scheme. The interview was headline news and water cooler talk for days.

"This is a very sad day for all of us at 60 Minutes and CBS News. Morley was a fixture, one of our pillars, and an inspiration in many ways."

In some of his later 60 Minutes pieces, Safer profiled the cartoonists of The New Yorker, interviewed the founder and staff of Wikipedia and reported on a billion-dollar art trove discovered in a Munich apartment. In his last story broadcast on March 13, he profiled the visionary architect Bjarke Ingels.

"Morley was one of the most important journalists in any medium, ever," said CBS Chairman and CEO, Leslie Moonves. "He broke ground in war reporting and made a name that will forever be synonymous with 60 Minutes. He was also a gentleman, a scholar, a great raconteur - all of those things and much more to generations of colleagues, his legion of friends, and his family, to whom all of us at CBS offer our sincerest condolences over the loss of one of CBS' and journalism's greatest treasures."

"This is a very sad day for all of us at 60 Minutes and CBS News. Morley was a fixture, one of our pillars, and an inspiration in many ways. He was a master storyteller, a gentleman and a wonderful friend. We will miss him very much," said Jeff Fager, the executive producer of 60 Minutes and Safer's close friend and one-time 60 Minutes producer.

CBS News President David Rhodes said, "Morley Safer helped create the CBS News we know today. No correspondent had more extraordinary range, from war reporting to coverage of every aspect of modern culture. His writing alone defined original reporting. Everyone at CBS News will sorely miss Morley."

Safer was a familiar reporter to millions when he replaced Harry Reasoner on 60 Minutes in 1970. A much-honored foreign correspondent, Safer was the first U.S. network newsman to film a report inside Communist China. He appeared regularly on the CBS Evening News from all over the world, especially Vietnam, where his controversial reporting earned him peer praise and government condemnation.

"Morley Safer helped create the CBS News we know today. No correspondent had more extraordinary range, from war reporting to coverage of every aspect of modern culture."

Safer's piece from the Vietnamese hamlet of Cam Ne in August of 1965 showing U.S. Marines burning the villagers' thatched huts was cited by New York University as one of the 20th century's best pieces of American journalism. Some believe this report freed other journalists to stop censoring themselves and tell the raw truth about war. The controversial report on the "CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite" earned Safer a George Polk award and angered President Lyndon Johnson so much, he reportedly called CBS President Frank Stanton and said, "Your boys shat on the American flag yesterday." Some Marines are said to have threatened Safer, but others thanked him for exposing a cruel tactic. Safer said that the pentagon treated him with contempt for the rest of his life.

He spent three tours (1964-'66) as head of the CBS Saigon bureau. His helicopter was shot down in a 1965 battle, after which Safer continued to report under fire. In 1990, he penned a memoir of his Vietnam experience, "Flashbacks: On Returning to Vietnam" (Random House), in which he goes back to reminisce and to interview the enemy's veterans.

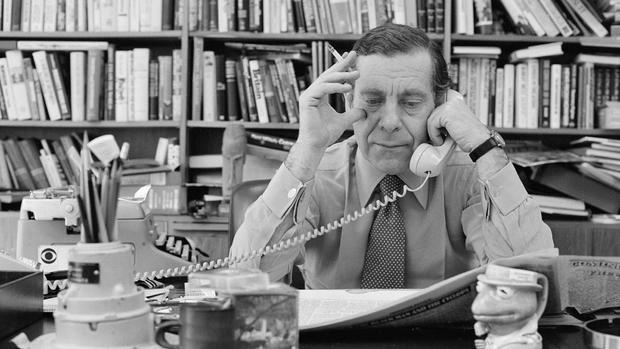

When he joined Mike Wallace at the beginning of 60 Minutes' third season, they toiled to put stories on the air for a program that dodged cancellation each season. But their work was immediately recognized with an Emmy for Safer's 1971 investigation of the Gulf of Tonkin incident that began America's war in Vietnam. The two pressed on for five years, moving the broadcast from the bottom fourth to the middle of the rankings. Then in August 1975, with a new Sunday evening timeslot, Safer put 60 Minutes on the national stage. Interviewing Betty Ford, the first lady shocked many Americans by saying she would think it normal if her 18-year-old daughter were having sex. The historic sit-down also included frank talk about pot and abortion.

By 1978, the broadcast was in Nielsen's Top 10. Safer's eloquent, sometimes quirky features balanced out the program's "gotcha" interviews and investigations, perfecting the news magazine's recipe. It became the number-one program for the 1979-'80 season - a crown it won five times. 60 Minutes remained in the top 10 for an unprecedented 23 straight seasons.

It was another Safer story that would become one of the program's most honored and important. "Lenell Geter's in Jail," about a young black man serving life for armed robbery in Texas, overturned Geter's conviction 10 days after the December 1983 segment exposed a sloppy rush to injustice. Safer and 60 Minutes were honored with the industry's highest accolades: the Peabody, Emmy and duPont-Columbia University awards. 60 Minutes founder Don Hewitt often pointed to the story as the program's finest work.

Safer hit more journalistic home runs, but sought out the odd stories that piqued his curiosity. The offbeat tales were more suited to his raconteur style and cultural sensibility. He found esoteric subjects all over the world and here in the U.S., ranging from a tiny Pacific island nation economically dependent on guano to the strange choice of tango dancing as a national hobby for the shy people of Finland to the strange yet harmonious stew of cowboys and artists in the Texas town of Marfa -- all narrated in his drolly delivered and precise prose. His conversational wit with his subjects was just as sharp as his written word. In a profile of the prim Martha Stewart, a smirking Safer passed her livestock pen and said to the domestic diva, "Your barnyard? It's remarkably odor-free."

Some of these features had national impact, however, like his November 1991 report, "The French Paradox," which connected red wine consumption to lower incidents of heart disease among the free-eating French. Wine merchants say this report was single-handedly responsible for starting the red wine boom in America. His 1993 segment "Yes, But is it Art?" enraged the modern art community when it criticized expensive, contemporary installations featuring household items like toilets and vacuums. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City may have held a grudge; years later, it refused to allow Safer onto its premises to review a Jackson Pollock retrospective for CBS Sunday Morning.

Safer's life was a work of art into which 60 Minutes fit seamlessly. He vacationed in Europe, often combining field trips for his stories. He made a regular pilgrimage to The American Academy in Rome to hone his painting skills, a hobby he began from an early age. He mounted a small exhibition of his paintings in 1985. He also had a special affinity for cars and did 60 Minutes segments on England's Rolls Royce and Italy's legendary Lamborghini. He owned a silver 1985 Ferrari convertible, which he had raced occasionally and also owned a Bentley when he lived in London, bought with his winnings from a card game.

Other highlights from Safer's 60 Minutes work include a poignant segment in 1978 called "The Music of Auschwitz," about an inmate who played in an orchestra to avoid the Nazi gas chambers; his 1979 profile of Katharine Hepburn; "The Beeb," a 1985 Emmy-winning take on BBC Radio; "The Enemy," the 1989 story for which Safer returned to Vietnam; and in 1979, "Marva," about Chicago teacher Marva Collins, whose alternative school for disadvantaged kids proved such students could excel. Safer's follow-up on "Marva" in 1996, in which he debunked a subsequent book that claimed Collins' students would not succeed in the long run, earned him his fourth duPont-Columbia University award.

In addition to the four duPonts, Safer won every major award, including the Paul White Award from the Radio and Television News Directors Association in 1966 when he was only 35 -- an award usually given for lifetime achievement. The other awards given to Safer over his long career include three Peabody awards, three Overseas Press Club awards, two George Polk Memorial awards, a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism first prize for domestic television, the Fred Friendly First Amendment award, 12 Emmys and a Chevalier dans l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres from the French Government.

CBS News hired the Canadian-born Safer in 1964 in London, where he was a correspondent for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He got the job in an odd turn of events. One of Safer's CBC colleagues seeking a job with CBS sent a demo tape of a roundtable he anchored that included Safer. CBS news executives liked Safer better and gave him a job in the London Bureau. The young correspondent took over his new job behind the desk once occupied by another CBS legend, the late Edward R. Murrow. After a year, he was asked to open the Saigon Bureau to report on the simmering conflict in Vietnam. He was then named bureau chief in London in 1967 and reported on a variety of foreign stories beyond Britain, many of them risky assignments, including the Nigerian-Biafran War, the Middle East conflict and the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia.

During this period he also filmed the historic CBS News Special Report "Morley Safer's Red China Diary" (August 1967), the first broadcast by a U.S. network news team from inside Communist China. Safer's Canadian citizenship helped get him into the country posing as a tourist interested in archeology. He and his cameraman, John Peters, were able to film the everyday lives of Chinese with a home movie camera. In a close call, suspicious authorities took Safer and Peters to meet an archeologist, who tested his knowledge. Safer knew enough about China's archeological periods to avoid arrest.

Safer's reporting and writing also appeared on the CBS News documentary series, "CBS Reports." He had a regular feature on CBS Radio, "Morley Safer's Journal," that ran in 1970s. In May 1994, he hosted "One for the Road: A Conversation with Charles Kuralt and Morley Safer," a CBS News special marking Kuralt's retirement.

Safer was born Nov. 8, 1931 in Toronto and eventually became an American citizen, holding a dual citizenship. Telling MacLeans he felt "stateless," he believed this status was an advantage. "I bring a different perspective and I have no vested interests," he told the magazine in 1998.

Growing up, he was influenced by the writing of Ernest Hemingway and decided he would be a foreign correspondent. He attended the University of Western Ontario for only a few weeks when he dropped out to begin writing for newspapers. He first wrote for the rural Woodstock Sentinel-Review before landing a job with the much larger London (Ontario) Free-Press. He then went on to England with the help of the Commonwealth Press Union, which promised to place him in a job there. After a short stint on the Oxford Mail and Times, Reuters hired Safer in London in 1955. When he returned late that year, he found work as an editor and reporter in the Toronto headquarters of the CBC. He was chosen to produce "CBC News Magazine" in 1956, on which he also occasionally appeared . His first on-camera work was on assignment for the CBC covering the Suez Crisis in November 1956.

The CBC sent him back to London in 1961, from which he covered major stories in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, including the war for Algerian Independence, until he joined CBS. He was the only Western correspondent in East Berlin the night the Communists began building the Berlin Wall in August 1961.

Safer was asked to characterize his legacy as a journalist in a November 2000 interview with the American Archive of Television. "I have a pretty solid body of work that emphasized the words, emphasized ideas and the craft of writing for this medium. It's not literary, I wouldn't presume to suggest that. But I think you can elevate it a little bit sometimes with the most important part of the medium, which is what people are saying -- whether they're the people being interviewed or the guy who's telling the story. It's not literature, but it can be very classy journalism."

He is survived by his wife of 48 years, Jane, one daughter, Sarah Bakal, her husband, Alexander Bakal, three grandchildren, a sister, and brother, both of Toronto.

Funeral arrangements are private. A memorial service will be announced at a later date.