60 Minutes Presents: On the 60 Minutes Menu

Welcome to 60 Minutes Presents. Tonight, we have three flavorful stories on the 60 Minutes menu. We begin with a yogurt entrepreneur.

Chief of Chobani

At a time when Americans are debating whether immigration and refugees are a good thing or a bad thing for the country, it is sometimes noted that Tesla, Google, eBay, and Pepsi Cola are all either founded by or currently run by immigrants, and, in one case, a refugee. It's a reminder that foreigners don't always take jobs from Americans, sometimes they create them. And of all the success stories none seems more relevant to the current debate than the tale of Hamdi Ulukaya, who came here from Turkey 24 years ago on a student visa with almost no money. As Steve Kroft first reported in April, Ulukaya is now a billionaire who has changed American tastes with his Chobani yogurt, resurrected the economy in two communities, and drawn praise and some hostile fire for the way he's done it.

He is a familiar, paternal presence on the factory floor, where everyone calls him Hamdi.

Hamdi Ulukaya: Hey brother, how you doing?

He oversees every detail of a product line that barely existed a dozen years ago. Greek-style yogurt—a thicker, tangier version of the dairy product that Ulukaya popularized here and named Chobani. It's now the best-selling brand in America.

Steve Kroft: What is the word, "Chobani," mean?

Hamdi Ulukaya: It means shepherd.

Steve Kroft: Shepherd?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Shepherd. It's a very beautiful word. It represents peace. And it meant a lot to me because, you know, I come from a life with shepherds and mountains and all that stuff.

His family raised goats and sheep and made cheese and yogurt in a small Kurdish village in Eastern Turkey. During the summer months, they would move to the mountains and graze their flock under the stars. He says he was born on one of those trips but he doesn't know the date or the year.

Steve Kroft: So how did you come not to know your birthday?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Yeah, in the old days, you know-- the nomads they didn't deliver babies in the hospitals.

"[Chobani means] shepherd. It's a very beautiful word. It represents peace. And it meant a lot to me because...I come from a life with shepherds and mountains and all that stuff." Hamdi Ulukaya

Steve Kroft: Midwives?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Midwives, yeah. They would register when they come back. The registration officer would put everybody in January. Says it's easy for math. Like, 70 percent of our town at that time, born in-- somehow in-- January. I'm January 20th.

Hamdi Ulukaya: This reminds me of home.

He came to the U.S. at 22, a passionate, idealistic student who had gotten in trouble with Turkish authorities for writing articles sympathetic to the Kurdish rights movement. He was hauled in for questioning and decided it might be a good idea to leave.

Steve Kroft: Did you speak any English when you came?

Hamdi Ulukaya: No.

Steve Kroft: None?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Zero

Steve Kroft: No family, no--

Hamdi Ulukaya: Nothing. Nothing.

Steve Kroft: No friends?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Nobody. No.

It took him a year to find his footing in upstate New York where he spent the next decade finishing his studies, working on a dairy farm and starting a modest feta cheese business here one day he spotted an ad.

Hamdi Ulukaya: It said, "Fully equipped yogurt plant for sale." And it has a picture in front. It said 1920 on the back. There was small, small picture of various per-- parts of the plant. And I called the number.

The real estate agent said the 85-year-old factory was owned by Kraft Foods which had decided to get out of the yogurt business.

Hamdi Ulukaya: And I asked for the price. And he says $700,000. I mean, you cannot even get a tank with $700,000. How could this be? So I didn't ask the second time because I didn't want him to think that I--

Steve Kroft: Didn't believe him?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Yeah.

Steve Kroft: Or get him to reevaluate the price?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Yeah, he says, "Oh, maybe-- we're asking too little."

Sensing an opportunity Hamdi set off to the small village of New Berlin, New York, to have a look. There he found the last employees of the last plant in the area closing it down.

Hamdi Ulukaya: I remember like yesterday. It's like this sadness in this whole place. Like as if somebody died, like, somebody important died.

Steve Kroft: Two hundred jobs?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Two hundred jobs was gone.

Former employees Frank Price, Maria Wilcox and Rich Lake were among the mourners that day.

Rich Lake: Your whole livelihood's gone. You don't really know what you're gonna do or where you're gonna go.

Steve Kroft: So in comes this guy. Did you think he was for real?

Rich Lake: Honestly, it was a little farfetched sounding at first. There was a little bit of doubt. At least for me there was. You know, I mean--

Hamdi Ulukaya: It's OK. I doubted myself too.

He didn't have any money, but he managed to get a regional bank and the Small Business Administration to split the risk of a million-dollar loan...that put Chobani in business and allowed Hamdi to hire his first five employees four of whom had been let go by Kraft.

Hamdi Ulukaya: And we had no other ideas what we were going to do next.

It would take them two years to come up with a product and figure out how to produce it. Hamdi spent most of his time in the plant, except to grab two meals a day at the local pizzeria owned by another immigrant Frank Baio and his wife Betsey.

Hamdi Ulukaya: This is the only place in my, you know, in my early days of coming here, this is the only place you can come and connect to life again and society and go back to whatever you do.

Frank Baio: And I want to say something, 'Scuse me if I interrupt you. Before Hamdi showed up in this town, I was the king.

Steve Kroft: What did you think of his plans?

Frank Baio: Well. let's put it to you this way: I kind of felt sorry because I don't think he know what was get into it. I mean, I-- you figure for Kraft to shut it down, who the hell is this guy that he's gonna open up and make it right, make it going?

Almost all of the early Chobani meetings took place here…along with some small celebrations. Betsey remembers one where Hamdi offered this toast.

Betsy Baio: He said, "Here's to wishing we could ever make 100,000 cases of yogurt in a week and not worry about the light bill." I said to my husband, "I'm gonna feel so bad when he loses his shirt 'cause he's never gonna sell 100,000 cases in a week."

Actually it would take only a year. The first order of Chobani yogurt –150 cases-- was delivered to a kosher grocery store on Long Island in October of 2007…no one knew if there would be another.

Hamdi Ulukaya: The store manager called me and said, "I don't know what you're putting into these cups. I cannot keep it on shelf. Don't tell me what you're putting in there." At that moment, I knew this was-- like, three months in, this was not going to be about if I could sell it. It was going to be about can I make enough.

It would require more machines, bigger facilities, more milk from the surrounding dairy farms, and a lot more people. Between 2008 and 2012 production of Chobani yogurt grew to as much as two million cases a week, revenues reached a billion dollars a year and the number of employees shot up to 600 ... It's now roughly a thousand.

Hamdi Ulukaya: Anybody in the community who wanted to work for those years would find a job at Chobani. Anybody, we were hiring. And if they were not working for us, they were working for the contractors that were doing job for us. Because the-- my-- my number one thing is I was gonna hire everyone local before I go outside.

Hamdi's recruiting effort included a stop at a refugee resettlement center in the city of Utica 40 miles away, where he heard they were having trouble finding people work.

Hamdi Ulukaya: They said, "Well, the language is a barrier. And transportation." I said, "OK, let's try some. I will hire translators. And we'll provide transportation. Let them come and make yogurt with us.

Steve Kroft: And they worked out?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Oh, perfectly. And they are the most loyal, hard, working people along with everyone else right now in our plant in here, we have 19 different nationalities, 16 different translators.

By 2012, the capacity of the plant in New Berlin had maxed out. They were running out of people, running out of milk and running out of room. So Hamdi decided to build a second facility -- the largest yogurt plant in the world, in the town of Twin Falls, Idaho, all based on a sketch he'd roughed out on a napkin at Frank's pizzeria.

Hamdi Ulukaya: And if you look at the plant and the-- and the napkin, it's basically the similar-- similar design. The piping in this plant is-- if you put it together-- from here to Chicago and we built them less than a year.

There were some initial growing pains: a shipment had to be recalled because of mold contamination and early production delays necessitated an emergency loan. But the business survived and has thrived in large part because of Hamdi's competitive nature.

Hamdi Ulukaya: I love innovation, I love competing. I hate my competitors.

Steve Kroft: You hate your competitors?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Of course, I do. I wanna beat them up.

Steve Kroft: You want to make Dannon yogurt and Yoplait suffer?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Back to France. Just kidding aside. What I mean is you cannot be in the world of business-- when you don't have this consciousness of winning. But in a right way.

Today the Twin Falls plant has 1,000 employees with above average wages and generous benefits. It pumps more than $2 billion-a-year into the regional economy, which is now running at close to full employment. It's allowed Hamdi to hire fellow immigrants and refugees, not instead of American workers but alongside them.

We met two of them in Twin Falls, sisters, and agreed not to use their names or disclose the Middle Eastern country they fled because they fear reprisals from the human traffickers that separated them from their family then abandoned them as young girls on the street corner in Eastern Europe.

Steve Kroft: How did you manage to get out?

Sister 1: Took us a long time. I prefer really not to talk about it because it is really painful--

Sister 2: It's painful, yeah.

Steve Kroft: Would you have survived if you had stayed there?

Sister 1: No.

Steve Kroft: You're sure of that?

Sister 1: Yeah. Definitely. I was not sitting here alive if I was not leaving.

Hamdi Ulukaya: They got here legally. They've gone through a most dangerous journey. They lost their family members. They lost everything they have. And here they are. They are either going to be a part of society or they are going to lose it again. The number one thing that you can do is provide them jobs. The minute they get a job that's the minute they stop being a refugee.

Hamdi Ulukaya insists he's not an activist just a businessman. But the fact that he comes from a Muslim country, supports legal immigration and helps refugees has not been universally popular in Idaho, one of the most conservative states in the country.

During the 2016 Presidential Election, Chobani was attacked by far-right media, including Breitbart claiming it had brought refugees, crime and tuberculosis to Twin Falls, none of which is true yet both Hamdi and the mayor of Twin Falls received death threats.

Steve Kroft: One publication had a headline that said, "American yogurt tycoon vows to choke U.S. with Muslims."

Hamdi Ulukaya: Yeah.

Steve Kroft: People targeted you?

Hamdi Ulukaya: Yeah, It was an emotional time. People, you know, hate you for doing something right. I mean, what can you do about that? There's not much you can do.

The situation has cooled somewhat and Hamdi enjoys the full support of Idaho's very popular and very conservative Governor Butch Otter.

Butch Otter: I think his care about his employees, whether they be refugees or they be folks that were born 10 miles from where they're working-- I believe his advocacy for that person is no different. And there's nothing wrong with that.

We traveled with Ulukaya to Europe, where he has made the international refugee crisis the focal point of his personal philanthropy. He's donated millions to help survivors like these in Italy.

Hamdi Ulukaya: What's your name?

...who risked everything fleeing Iraq, Syria and Africa in hopes of finding a better life. He's also enlisted the support of major U.S. corporations in the cause and pledged to give most of his fortune to charity.

Hamdi Ulukaya: She died?

Refugee: Yes.

Hamdi Ulukaya: And the kids died too?

Hamdi says he had no idea that things would turn out the way they have when he came to America 24 years ago and bought that shuttered yogurt factory in upstate New York. He is now showing his gratitude. In 2016, he gave 10 percent of all of his equity in Chobani to his employees.

Hamdi Ulukaya: It's not a gift. It's not a, "Oh look how nice I am." It's a recognition. It's the right thing to do. It is something that belongs to them that I recognize. That's how I see it.

Two days after our story first aired last year the far-right radio host Alex Jones posted a fresh round of accusations that Chobani was quote "importing migrant rapists." This time, the yogurt company sued. Last May, Jones settled the case and expressed regret for the way he characterized the employees of Chobani.

Produced by Michael Rey and Oriana Zill Granados. Chrissy Jones, associate producer.

The Rum War

The relationship between Cuba and the United States was stuck in pretty much the same bad place for half a century. But things have been changing at a dizzying pace in the last couple of years.

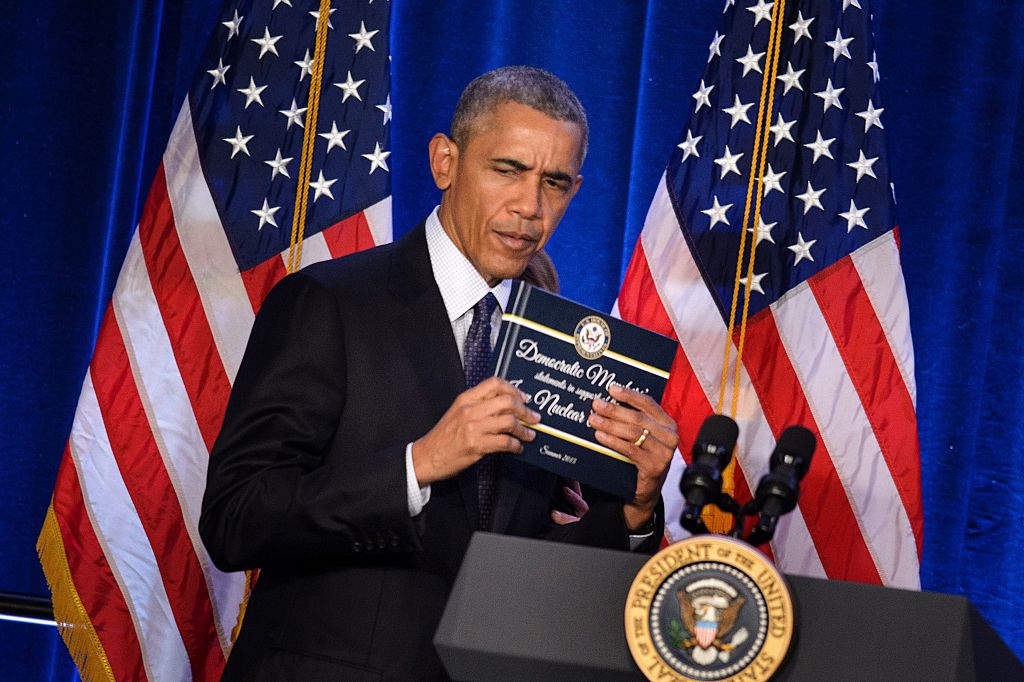

President Obama started the thaw in the relationship by re-establishing economic ties and easing restrictions on travel. Now President Trump has announced plans to undo many of those moves. And Fidel Castro, who spent 50 years poking his thumb in the eye of every American president, has died.

Whatever happens, there's already a war underway that has the U.S. and Cuba on the rocks. As we first reported last year, it's a war over rum, specifically, over two different versions of Havana Club rum and it's as bitter as the Cold War ever was.

It's a Tuesday afternoon at El Floridita in Old Havana, and we and lots of other visitors to Cuba are filing in and filling up at the bar that calls itself the "Cradle of the Daiquiri." Head bartender Alejandro Bolívar needs to double up on rum bottles just to keep up with demand.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How many bottles do you go through a day? Any idea?

Alejandro Bolívar: So it's at-- it's between 60 and 80-- 80 bottles per day.

Sharyn Alfonsi: That's a lotta daiquiris.

Alejandro Bolívar: Yeah. Plenty of empty bottles.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Oh my gosh. Is this just from today?

Alejandro Bolívar: Yeah. Today, yeah.

All those bottles were filled with Havana Club rum, produced by a 50-50 joint venture between the Cuban government and the French beverage giant Pernod Ricard, which sent Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne to Cuba to run the business. We met him in a place that's rarely open to outsiders: a warehouse stacked to the ceiling with oak barrels full of rum.

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: We built a very great success with Havana Club. When we started the partnership in 1993 we sold five million bottles a year. Today, we sell 50 million bottles a year.

50 million bottles, 11 million of them sold here in Cuba. The tourists drinking Havana Club are obvious, but we went looking down the side streets, and found locals drinking it too…at domino games and dance halls and discos…and sipping it along Havana's seafront promenade, the Malecón.

To distill and age all that rum, the Cuban government and Pernod Ricard rely on Asbel Morales, Havana Club's master rum-maker. He loves talking about rum, but he says to really understand it, you have to drink it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Es muy bueno.

Asbel Morales: Muy Bueno.

"The first sip will impact you the most," he said, "and make you anxious for a second."

Sharyn Alfonsi: I am anxious to continue the second sip.

And the third, and the fourth, and the Cohiba cigar that he says pairs perfectly with this Havana Club. As we drank and smoked, Morales told me "Cubans are born with a "rum gene."

And to be real Havana Club rum, he said, it must be made from Cuban sugarcane and aged in the hot and sticky Cuban climate.

Here's where it gets confusing: this is another bottle of Havana Club rum. Exact same name – but you can see right here this one is made in Puerto Rico. And it's made by Bacardi.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How in the world can you say Havana Club when you're making it in Puerto Rico?

Rick Wilson: I-- just the way that you say I'm calling it Arizona Iced Tea and I'm not making it in Arizona.

Rick Wilson is an executive at Bacardi, originally a Cuban company, and now the largest privately held liquor business in the world.

Rick Wilson: The true Havana Club made with the recipe of the original founders is the Havana Club that Bacardi is making and selling here in the United States.

Bacardi bought that original recipe from the family of this woman, Amparo Arachabala.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And it was one of the wealthiest families in Cuba before the revolution?

Amparo Arachabala: Yes. Definitely. Definitely.

The Arechabala fortune was built on sugar, and shipping, and rum…Havana Club Rum. Like hundreds of other Cuban companies, theirs was confiscated shortly after Fidel Castro's revolution in 1959.

Amparo Arechabala: They took over the company on December 31st, 1959.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And do you remember that day?

Amparo Arechabala: I remember that day vividly. My husband came home. He went to work early and then he came home and he says, "They've thrown us out. It's over."

Sharyn Alfonsi: It's over, he said.

Amparo Arechabala: He said, "It's over."

All of their assets gone, Amparo and her husband Ramon were ordered to leave Cuba with only the clothes on their backs.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And how much money did you have in your pockets?

Amparo Arechabala: Absolutely nothing. Nothing. Nothing. Nothing.

Sharyn Alfonsi: What was it like when you got on the plane?

Amparo Arechabala: Everybody in the entire plane was crying. And I remember I looked out the window as we were taking off and I say to my husband, "Take a good look because you're not gonna see it again."

In Cuba, the Arechabalas and Bacardi had been competitors, each making and selling popular brands of rum. But when the revolution came, Rick Wilson says Bacardi had an advantage.

Rick Wilson: Bacardi, unlike most other Cuban families and companies, had assets outside of Cuba.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Is that the reason they were able to survive?

Rick Wilson: Yes. Because we could continue to produce and sell our product. Unlike the Arechabalas. The Arechabalas, everything they had was in Cuba. Everything.

Everything except the recipe for Havana Club rum. The Arechabalas eventually sold it to their old rival Bacardi, which makes this version at its distillery in Puerto Rico.

They did it to compete with this version made by the Cuban government and their partner Pernod Ricard. That set off the longest bar fight ever.

It has been fought both in the courts, where the latest lawsuit is pending, and the marketplace, between two of the world's largest liquor companies. Pernod Ricard produces Absolut vodka, Chivas Regal scotch, Beefeater gin. Bacardi makes Grey Goose Vodka, Dewar's Scotch, And Bombay Sapphire Gin.

And now they both make Havana Club rum, and they both try to claim the moral high ground.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And it wasn't that Pernod Ricard had just stepped up and they looked to be competitors to you.

Rick Wilson: No. We don't mind competition from Pernod Ricard or anyone else. Pernod Ricard, though, did and is partnering with the Cuban government who has confiscated the assets of a family. No compensation paid.

Sharyn Alfonsi: It's hard to believe that a company like Bacardi is just making a moral argument. That it's just about…

Rick Wilson: We're-- we're not. We're makin' a moral and a legal argument.

Sharyn Alfonsi: OK. And the legal argument is?

Rick Wilson: Um, theft. I mean it comes down -- it's stolen property. That's what it comes down to.

Sharyn Alfonsi: The Bacardi family will say that this Havana Club is stolen property.

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: Well, you see the place. We are here in our distillery. It was built in 2007.

Sharyn Alfonsi: And none of these facilities were used—before the revolution?

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: None of these facilities were used before the revolution, no.

And Asbel Morales dismisses the argument that the Havana Club rum he produces for Pernod Ricard in Cuba is not the real thing because it's not made from the original Arechabala family recipe.

"The recipe remains in this land," he said. "It is here in this climate, the culture."

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: It's very simple. To make a Cuban rum, you need to make it in Cuba. You know, it doesn't-- take more than that. You cannot make Cuban rum in Puerto Rico.

And the Arechabalas cannot, he insists, claim to own the Havana Club brand decades after abandoning it.

Sharyn Alfonsi: How do you feel that they used that word about the family, saying they abandoned the brand?

Amparo Arechabala: They can say whatever they want. They can say that we abandoned. We didn't abandon anything. They threw us out.

The Castro government did that. The French company Pernod Recard came along much later, and turned the Cuban Havana Club into a global brand and an icon of Cuban culture. We found the logo everywhere we went in Cuba: on every glass in every bar…on taxi drivers and parking attendants…on the chairs we did our interviews in…and at the tourist market, on artwork and tote bags and T-shirts, right alongside other symbols of Cuba.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you sell more Che T-shirts or more Havana Club T-shirts?

Man: Same.

Sharyn Alfonsi: About the same

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: When we sell a bottle of Havana Club in France, in England, or in Chile, we not only sell the liquid, we sell the soul of the country.

The one place in the world they can't sell their Havana Club at the moment is the United States, because of the trade embargo on Cuban products that's been in place since 1962.

But there is a way for Americans to have the Cuban version; in 2016, then-President Obama lifted limits on how much rum and cigars tourists can bring home from Cuba.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Will you be bringing rum home with you?

Woman: Yes. Lots of rum. We stocked up. Now we just need another case to bring it back in.

The makers of Cuban Havana Club aren't satisfied with just sending suitcases full of rum home with tourists. They want to ship containers full when the trade embargo is lifted.

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: In Cuba-- we know how to be patient. Look, all the rum sitting around us, all these barrels. It's years and years of aging. Years and year of work, of—dedication. We know that one day, we'll be able to sell our rum, Havana Club, the true Cuban rum made in Cuba, and that the U.S. consumer will have the chance-- the opportunity to enjoy it.

Consumers in the U.S. drink 40 percent of the world's rum, which explains why they're stacking barrels sky-high in Cuba in preparation.

Sharyn Alfonsi: This is all ready to go?

Jérôme Cottin-Bizonne: This is all ready to go.

For now, though, the trade embargo continues, and so does the court fight over who has the right to use the Havana Club name. On the streets of Havana, there's no disagreement on that point. We took a few bottles of Bacardi's version there to sample reaction.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Do you drink rum?

Players: Si!

Sharyn Alfonsi: Have you ever seen this before?

These men we found playing dominos on an old Havana side street were more than happy to try it…

Man: Similar.

Sharyn Alfonsi: Similar.

"It's good," he said, "but the Cuban is better quality."

Ernesto Iznaga: Color is different, the stamp is different. This is the real Havana Club. The symbol.

In a bar called Sloppy Joe's, manager Ernesto Iznaga wanted no part of Bacardi's Havana Club.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You don't even wanna try it.

Ernesto Iznaga: No.

Sharyn Alfonsi: You can just have a sip. You don't have to drink the whole bottle.

Ernesto Iznaga: No.

Sharyn Alfonsi: No?

Ernesto Iznaga: Sorry.

These are the front lines: two bottling lines in two countries. Each one producing Havana Club rum. Each claiming that its version is the only real and authentic one. Not so far apart in miles, but worlds apart in the rum war.

Produced by Rome Hartman. Associate Producer, Jack Weingart.

The Restaurateur

If you've eaten out in the past couple of decades, chances are a restaurateur named Danny Meyer has had a big impact on how your meal went. Since Meyer opened his first restaurant in 1985, the innovations in food, service and hospitality he's pioneered have been so widely copied they've changed the way America dines out. He now runs 15 restaurants, and Shake Shack, the burger joint he opened in 2004, has become a global, billion-dollar chain. But as Anderson Cooper first reported last fall, in Danny Meyer's most daring innovation to date: he is eliminating tipping in his restaurants, a move, which if successful, may radically alter the way restaurants do business.

Thousands of people line up every day to eat Danny Meyer's food. Here at Citi Field, the home of the New York Mets, some fans come early just to get a taste of Shake Shack. When we were there, the wait was almost an hour long.

Anderson Cooper: Have you been to your seat yet? Or you just came straight here--

Rob: No, no, no. We came straight in.

Anderson Cooper: To beat the line?

Rob: You have to. It's the only way you get a burger.

Anderson Cooper: Is it worth it?

Rob: It's very good.

Anderson Cooper: Really?

Rob: Yeah. Would you like one?

Danny Meyer says Shake Shack burgers taste so good because he makes them with the same high-quality ingredients he uses in his expensive restaurants, but that still doesn't explain why people are willing to stand in those long lines.

Anderson Cooper: It's burgers and it's fries. And it's shakes. You haven't reinvented the wheel here.

Danny Meyer: We are as sometimes as mystified as anybody as to what the magic of Shake Shack is. I think we know that this is fine-casual. This is a new way of dining--

Anderson Cooper: Fine-casual.

Danny Meyer: Fine-casual, which is marrying together the ethos and taste level of fine dining with the fast food experience.

Anderson Cooper: So you don't call it fast food.

Danny Meyer: When did you ever go to Shake Shack and find the experience to be fast?

We went with Danny Meyer to New York's City Madison Square Park – where he created the first Shake Shack in 2004.

Anderson Cooper: The reason I haven't had a burger before from Shake Shack is because of the line.

Danny Meyer: Instead of simply asking yourself, "Is the burger so good that you would choose to wait in line?" I think the question is, "What else are they getting out of the experience? And I think what fast food hijacked was the notion that people actually want to be with people. Their whole promise, was basically, "We're gonna get you out of here so quickly you'll never have to see a person. In fact, we're even gonna give you drive-through lines so you never have to get out of your car." And we're kind of doing the opposite of that.

Anderson Cooper: I'm gonna get a-- cheeseburger, a Shack Burger?

CASHIER: Shack Burger.

Danny Meyer: Shack Burger.

Anderson Cooper: Shack Burger, sorry. And a-- coffee milkshake and fries.

Anderson Cooper: There's something about the combination of the bun and the burger.

Danny Meyer: So if you think about it, a hamburger is basically two things. It's the bun and the meat. And what's great about this bun is that it doesn't fight you as you're eating it. It absorbs juices.

Anderson Cooper: It doesn't fight you?

Danny Meyer: It doesn't fight your teeth. I think it's a mistake if the bun is too big and too hard.

His attention to detail has made Meyer a leader in fast casual dining, or what he calls fine-casual. Although not the largest, it is the fastest growing sector of the restaurant business. Meyer believes many consumers want good food delivered in less time and at less cost than at a full-service restaurant.

Danny Meyer: And I think what fine-casual is doing is, "If you're willing to give up waiters and waitresses and bartenders and reservations and table cloths and flowers, we're gonna s-- we're gonna give you about 80 percent of the quality that you would have gotten in a fine-dining restaurant. We're gonna save you about 80 percent of the money you'd spend in a fine-dining restaurant. And we're gonna save you about 60 percent of the time."

Fine-dining is how Meyer started in the restaurant business more than 30 years ago. He opened his first restaurant, Union Square Cafe, in 1985 in what was then a seedy neighborhood in Lower Manhattan. Back then, people dined out less frequently, and expensive restaurants were often formal, and intimidating. Danny Meyer had a different vision.

Danny Meyer: I said, "Let's create a restaurant where you can feel great if you're dining alone." So we created a bar for dining at a time when you never got three-star food at a bar in New York City. That was the domain of coffee shops. I wanted to go to a restaurant where I could drink great wines by the glass, so I was just looking to break as many rules as I possibly could. But ultimately to create a restaurant that at the age of 27 would have been my favorite restaurant, if only it had existed.

Meyer has been fascinated with food since he was a child. He grew up in St. Louis -- the son of an entrepreneur and an art gallery owner who loved entertaining and cooking.

Anderson Cooper: Do you think about food all the time?

Danny Meyer: Constantly.

Anderson Cooper: Have you always?

Danny Meyer: I think I have, for whatever reason, since I was a little kid. I'd go to the St. Louis Cardinal baseball games and I was the guy that would get the whole hot dog, like everybody did. But I'd go to the relish station and I'd put a little ketchup on this bite, a little mustard on this bite, a little onion here, a little pickle relish here to see which I liked better.

Anderson Cooper: I, I don't know how to ask this. But, I mean, were you a chubby kid, if you were eating all the time?

Danny Meyer: I actually was a chubby kid-- by the time I got to be 12 years old, 12, 13, 14. And that's kind of how I always felt thereafter. And so it, it gives me great pleasure that today I can kind of eat as much as I want 'cause I know how to exercise. And I know how to balance it out. But it also probably put me in a position where I love seeing other people eat.

Today, Meyer's company, Union Square Hospitality Group oversees 15 different restaurants, all in New York – they operate upscale eateries, casual bistros, a cocktail lounge, and a neighborhood bakery.

What they all have in common is Danny Meyer's philosophy of hospitality – which he pioneered but has since become a standard for the industry.

Danny Meyer: Hospitality basically says that the most important business principle at work, way beyond that the food taste great, and by the way, if the food doesn't taste great you're never coming back here, but if the food tastes great, that alone doesn't not assure that you will come back here. So what hospitality does is it adds the way we made you feel, to how good the food tasted.

Anderson Cooper: So the experience of dining out for you is the most important thing?

Danny Meyer: I think the experience of how you are made to feel is the most important thing.

The key, he says, is to hire people who are intuitive and empathetic. He has more than 2,000 employees, and he trains them to pick up on the customers' cues.

Danny Meyer: Everyone on Earth is walking around life wearing an invisible sign that says, "Make me feel important." And your job is to understand the size of the font of this invisible sign and how brightly it's lit. So make me feel important by leaving me alone. Make me feel important by letting me tell you everything I know about food. So it's our job to read that sign and to deliver the experience that that person needs.

Anderson Cooper: This is the reservation system.

Scott Reinhardt:: Yes.

Danny Meyer: Are there any folks here that I'm supposed to be saying hello to today?

Scott Reinhardt:: We have a regular right here.

In the restaurant business, profit margins are razor thin and repeat customers are critical. Meyer has made an art of making his customers feel welcome, tracking their likes and dislikes.

Anderson Cooper: I've also heard you say that you always identify the boss at the table. W-- h-- I didn't realize there was a boss-- at each table. But how do you do that?

Danny Meyer: Well there-- there's no question in my mind that at every single table there's somebody who's got the biggest agenda. If it's two people doing business, there's someone who's trying to sell something to somebody else. And I think that if you can figure that out early on in the meal, and understand what is it gonna take for the boss to leave happy, it could be make sure that someone else gets to pick the wine. You just gotta pick up on those cues.

Meyer's most controversial innovation is also his riskiest. He is trying to eliminate tipping to combat pay inequities between servers – whose tips have gone up as menu prices have increased – and those who work in the kitchen, who under most state laws can't share in gratuities.

Anderson Cooper: So the cooks, dishwashers, they don't get any part of the tip?

Danny Meyer: They don't get any of it. And what I noticed after being a restaurateur for 30 years is that the growing disparity between what you can make in the dining room where tipping exists, and what you can make in the kitchen had the disparity had grown by 300 percent.

Meyer has so far eliminated tipping in ten of his restaurants. He's increased the base pay of both servers and kitchen staff and in some restaurants gives waiters a share of the weekly revenue. He has raised menu prices significantly, on average, nearly 25 percent. But when the bill comes, there's no line for leaving a tip.

Anderson Cooper: You call it "Hospitality included." Wha-- why? You don't-- you don't say, "No tipping."

Danny Meyer: So by saying, "Hospitality included," it's basically saying, "You see that price that it costs to get the chicken? That includes everything. That includes not only the guy that bought the chicken and the guy that cooked the chicken, but it also includes the person who served it to you and how they made you feel."

Anderson Cooper: So for the customer, in the end, is the bill the same?

Danny Meyer: The bill, by the time you get your bill, whatever shock you did or didn't feel when you saw the menu prices should completely dissipate, because you should say, "That's exactly what it would have been if they hadn't had this new system"—

Anderson Cooper: Plus at the end of the meal, you don't have to deal with the hassle of figuring out what to tip.

Danny Meyer: That's absolutely true and let's face it, the end of the meal tends to be when people have had more wine than the beginning of the meal, and sometimes people make honest mistakes.

Anderson Cooper: There's not a lot of restaurants though-- who are following your lead.

Danny Meyer: That's absolutely true, and it kind of reminds me of--in 1990, when I decided to eliminate smoking at Union Square Café.

Anderson Cooper: That was long before the law actually--

Danny Meyer: It was 12 years before--

Anderson Cooper: --ended it.

Danny Meyer: --it became law. And so for me, it's almost immaterial who's doing it besides us. What matters is that – that we're doing it. It could be that we're slightly ahead of our time. But we're in it to win this thing.

Meyer reopened his first restaurant Union Square Cafe, in a new location in late 2016. It's another no-tipping restaurant. Minutes before the first customers arrived, Meyer was still making final adjustments determined to deliver a dining experience that would keep them coming back for more.

Danny Meyer: My mind doesn't shut up. And I'm constantly thinking about, "How could we do this better? How could we make this better? I don't want to ever open a restaurant that if it closed people just wouldn't care.

Anderson Cooper: I will say, I mean, it's been now 24 hours since I had my first burger at Shake Shack and a coffee milkshake. I have been thinking about it more than I have thought about food in a long time.

Danny Meyer: So all you need to know about me after all these questions is that nothing in the last 24 hours makes me happier than hearing what you just said.

Produced by Ruth Streeter. Kaylee Tully, associate producer.