The Music of Zomba Prison

Something unusual happened on the way to the Grammy Awards last year, an album was nominated from Malawi, a small country in southern Africa not exactly famous for its music. As we reported in October, the artists weren't polished pop stars but prisoners and guards, men and women in a place called Zomba, a maximum-security prison so decrepit and overcrowded, we heard it referred to as "the waiting room of hell." How could such beautiful music come from such misery? We went to Malawi to find out.

This is the music that brought us to Malawi, one of the least-developed nations on the planet. It's a place of staggering beauty. There's vast mountains, lush forests, and a long, idyllic lake. Drive through the countryside however, and you quickly see poverty is widespread. For the country's 17 million people, life is full of hardships.

Zomba is Malawi's only maximum-security prison and the music you're hearing comes from behind these walls. This prison was built to hold around 400 inmates. Today, there are 2,400 here.

What's so startling when you walk into the prison yard on a Sunday morning, is that everywhere you turn, there is music. A cacophony of choirs.

Many here are hardened criminals. Robbers, rapists, murderers. Others are casualties of a legal system that can be chaotic and arbitrary, where court files are routinely lost and most suspects have no legal representation.

In a small room off the yard, there's a prison band practicing every day on donated instruments. Those men in green are guards. They play side-by-side with inmates. Ian Brennan, an American producer who travels the world recording new music in unlikely places, heard about Zomba and, four years ago, flew to Malawi to check it out.

Anderson Cooper: You're taking a gamble. Because you go to places you don't necessarily know what's there, right—

Ian Brennan: No, no, no. We have no idea. It's a leap of faith every single time.

His was not the only leap of faith. Officer Thomas Binamo took one too. He helped found the prison band nine years ago, and wasn't sure what to think the day Ian Brennan showed up.

Thomas Binamo: I was quite surprised because I couldn't understand how this guy knew about us. And why would he be interested in our prison?

Anderson Cooper: It's not every day a white American knocks on the prison door and says he wants to come in?

Thomas Binamo: Yah it's true, it's not every day.

[Ian Brennan: What took you so long?]

Brennan saw promise in this prison, and the possibility of an album so he set up his microphones and asked anyone interested to write and sing songs about their lives – men and women, inmates and guards. It was something most had never done before.

Anderson Cooper: What were you hoping to find?

Ian Brennan: Well, you know, the thing we look for everywhere, which is, you know, music that resonates with us.It's just-- just this is-- this is what moves me. And hopefully it'll move someone else.

Anderson Cooper: And when you hear it, you know it.

Ian Brennan: Yeah. You feel it, usually.

Anderson Cooper: Even if you don't understand the words right away?

Ian Brennan: It's better when you don't understand the words. Because when you don't understand the words, you have to listen to what somebody means, not what they're saying. And if they mean it.

[Binamo in front of microphone singing "My Wife."]

Officer Binamo was reluctant to write and sing about his life, but when he did, Ian Brennan knew his music would be on the album. Just listen to what he came up with one morning when we were there -- a softly-sung ballad about the sudden death of his wife.

"You left without saying goodbye," he sings.

"You left behind the children too"

"They no longer cry"

Ian Brennan: He writes songs and plays as beautifully as someone can. He's reached that level of transcendence where it can't be better than it is. It just is. It's something that just hits you.

To fully appreciate the music here, you have to see the misery, but when we arrived at Zomba, authorities didn't want us to show what life is like for the prisoners. So, much of what we filmed, we had to record secretly, without the guards knowing. Inmates in Zomba are fed just one meal a day -- a small bowl of gruel made out of cornflower. The menu, we're told, rarely changes. On good days they get a few beans. On bad days, inmates say, there's no food at all.

Chikondi Salanje sang on the album nominated for a Grammy. He's doing time for burglary.

Anderson Cooper: Do you eat meat, chicken, beef?

Anderson Cooper: You're laughing. That's not good. When was the last time you had meat?

Chikondi Salanje: 2014… 25 December.

Anderson Cooper: Two and a half years ago on Christmas Day?

Chikondi Salanje: Yah

It's not just the lack of food, Zomba is so overcrowded prisoners say they only have enough room in their cells to sleep wedged against one another lying on their sides. Stefano Nyirenda also sang on the album.

Anderson Cooper: So you're sleeping on your side?

Stefano Nyirenda: When you want to turn, you have to do it together.

Anderson Cooper: Right next to each other?

Anderson Cooper: How do you sleep?

Stefano Nyirenda:: We just sleep. We have no choice.

Stefano is in for robbery and he is HIV-positive, as are around a quarter of Zomba's inmates. They occasionally get visits from an Italian nun, Sister Anna Tommasi who runs a small charity providing some food and legal aid to prisoners.

Anderson Cooper: If you were writing a postcard to somebody who had never been to this prison, how would you describe it here?

Sister Anna: Oh. I think it's impossible for somebody outside to get-- there are no words which could explain because--

Anderson Cooper: What life is like here?

Sister Anna: Yes, I think before you came, three days ago, if I had written anything, would-- do you think you could have had a clue?

Anderson Cooper: No.

Sister Anna: Sometimes I call it, it's the waiting room of hell.

Anderson Cooper: That's what this prison is like? Sometimes.

Sister Anna: Yeah.

If it is the waiting room of hell, salvation for Chikondi Salanje comes from music.

Chikondi Salanje: When I'm singing, I feel like I'm in another world. I don't feel like I'm in prison at all. It's only when I stop that I realize 'Oh, I'm still in prison.' When I'm singing I forget about everything else.

Anderson Cooper: When the music stops, that's when you realize you're in prison?

Chikondi Salanje: When we're singing the walls are no longer there. But when we stop, the walls return. And then we're back to counting the bricks again.

Chikondi wouldn't have to count the bricks much longer. After 5 years here, he was about to get released and when we were there, recorded a new song for Ian Brennan.

It's about leaving prison...and his fears of life as a free man.

[Chikondi (and Elias) singing "I Paid My Dues."]

"Don't call me a criminal, he sings."

"When I get home they'll reject me."

"When something goes missing, they'll accuse me of stealing."

"It hurts badly when you call me a criminal."

In the men's section of this prison, there are rooms where prisoners take classes taught by inmates and guards. There are also two small libraries where they pour over faded books, and a rundown computer room. But in the women's section, there is no library, no computers. There is little else but music.

Until Ian Brennan came along the women didn't have their own instruments, and they couldn't understand why he was interested in listening to their singing at all.

Ian Brennan: They really-- were-- believed that they were not singers or songwriters. I mean, they were pretty adamant about this. And just at the moment, I-- I was gettint pretty close to feelint like, "Well, you know, we-- we tried"-- one person stepped forward and said, "I've got a song." And then the minute she did that, they literally lined up.

Rhoda Mtemang'ombe was one of those women who stepped forward. The song she wrote for the Zomba prison album is called "I am alone."

Anderson Cooper: What does that mean?

Rhoda Mtemang'ombe: I have no parents. I have no husband, and I'm here in prison. So I realize there's no one who can help me. So I ask God to help me. He's the only one who can guide me across this huge river.

Rhoda is serving a life sentence here in Zomba. She's in for murder.

Anderson Cooper: Do you feel like you're glorifying criminals?

Ian Brennan: No. No, no, no. it's humanizing them--

Anderson Cooper: Humanizing--

Ian Brennan: --not glorifying them, at all, right? They've committed crimes. Many of them have learned from their experiences. This is about humanizing individuals--

Anderson Cooper: Wha-- wha--

Ian Brennan: --and that's for the benefit not of them; that's for the benefit of the listener.

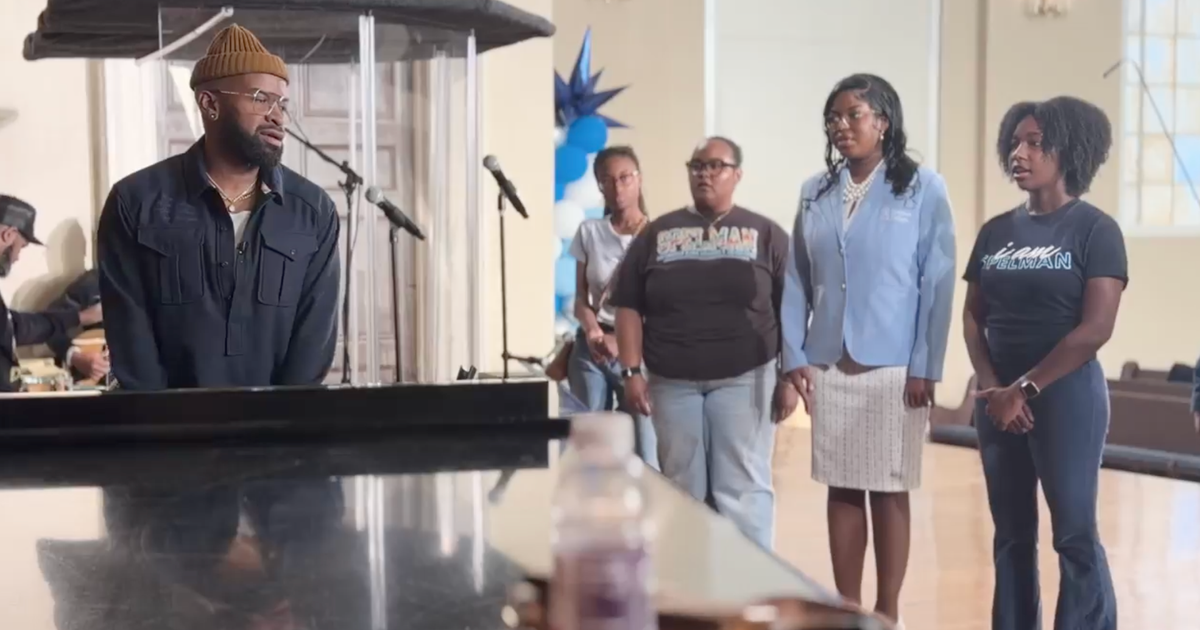

The album Ian Brennan recorded at Zomba did not end up winning the Grammy last year and it hasn't turned a profit either. Brennan has paid the musicians and they have a contract to receive more money if there are future earnings. When he showed up at Zomba with his wife Marilena last May to present the prisoners with some gifts and their Grammy nomination certificate, it was cause enough for celebration though some of the singers like Stephano Nyrenda still had questions about what a Grammy award really was.

Stephano Nyrenda: Can I ask a little question?

Anderson Cooper: Yeah, of course.

Stephano Nyrenda: This trophy, does it have any money inside of it, or is it just a small prize?

Anderson Cooper: It's just a token, there's no money inside the, inside the award.

Being nominated for a Grammy has not changed life for the inmates inside Zomba or for guards like Thomas Binamo living just outside the prison walls. But they are still writing music, and in September, released a whole new album. It's called "I Will Not Stop Singing." Inside this prison, it's the only promise they have the power to keep.

To donate to the Zomba Prison Project, visit http://www.sixdegreesrecords.com/zomba-prison-project-donations

Produced by Michael H. Gavshon and David M. Levine. Jolly Ntaba, associate producer.