October 2020: Alexey Navalny on the poisoning attack he survived and why he thinks Putin was behind it

Russian President Vladimir Putin's political opposition has taken to the streets once again in cities across the country. They were ignited by the imprisonment of opposition leader Alexey Navalny, who is said to be near death in the prison infirmary, partly the result of a 24-day hunger strike, which he ended Friday.

Last month, President Biden announced new sanctions against Russia for incarcerating Navalny, who has become an international symbol of freedom in an increasingly autocratic country.

Navalny was taken into custody as he returned to Russia in January after treatment in Germany for a near-fatal poisoning. We spoke last fall in Berlin, as he recovered. As we reported then, he told us he was aboard a flight from Siberia to Moscow when he began to feel very sick.

Alexey Navalny: I said to the flight attendant, and I kind of shocked him with my statement, "Well, I was poisoned and I'm gonna die." And I immediately lay down on-- onto his feet.

Alexey Navalny was on a flight to Moscow from Siberia where he had been campaigning against Putin's party in a local election when he collapsed with no pain but knowing he was dying.

Alexey Navalny: Actually, every cell of your body just are telling you that, "Body, we are done."

One of the other passengers turned on his phone and captured Navalny moaning in anguish.

The pilot made an emergency landing in Omsk. Where medics, thinking Navalny must be a drug addict, administered the usual treatment for an overdose and rushed him to a local hospital where they said he wasn't poisoned but wouldn't let him leave for days.

Alexey Navalny: Well, it was a big fight. They thought that after 48 hours, this poison would be untraceable. And they just keep me there until this 48 hours will be gone.

Navalny is under constant surveillance. His wife, Yulia, says government agents were at the hospital controlling access to her husband and she believes calling the shots. At the time, Navalny was in a coma, unaware that Yulia was waging a public campaign to encourage western diplomatic pressure. And…

Lesley Stahl: Did you write a letter to Putin?

Yulia Navalnaya: Yeah, I did it.

Lesley Stahl: "Dear Mr. Putin… free my husband."

Yulia Navalnaya: I wrote, like, "I insist that he should do it."

Lesley Stahl: "I demand you free my husband."

Yulia Navalnaya: Yeah.

Alexey Navalny: It was an online campaign, "Let him out!" And Putin thought it would be safe for him, just let me out after the 48 hours.

So after 48 hours, the Russian government allowed him to be flown by air ambulance to a hospital in Berlin known for its experience with victims of poison attacks.

Lesley Stahl: And I gather they suspected poison right away?

Alexey Navalny: Yes, of course.

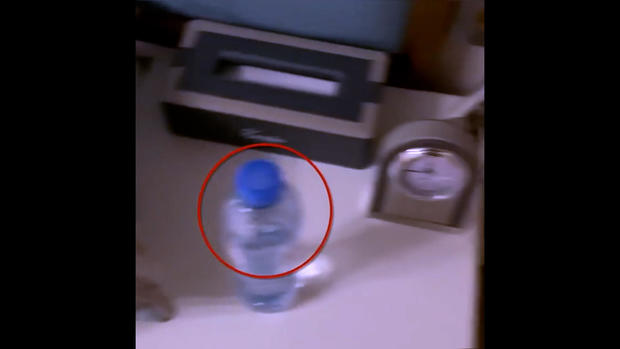

Meanwhile, his team in Siberia searched his hotel room, collecting things Navalny may have touched, like this water bottle, which the doctors in Berlin sent along with a blood sample to a German military lab to see exactly what the poison was. And the answer was Novichok.

Alexey Navalny: They discover Novichok, this nerve agent in my blood, inside of body, on my body and on this bottle from the hotel. So-- that's why we now-- we know that I was poisoned in the hotel. Because I, well, it's again, it's just pure speculation, because no one knows what-- what-- what happened exactly. But I think that when I was-- maybe put some clothes with these-- with this poison on me, I touch it with the hand, and then I sip from the bottle. So this nerve agent was not inside of a bottle but on the bottle.

Novichok is a highly toxic nerve agent said to be ten times more potent than sarin gas. Labs in France and Sweden corroborated the finding: there's no doubt it was military-grade Novichok.

Alexey Navalny: It's maybe-- it's the most toxic agent invented by the humans. So it's new type of Novichok, which proves that, unfortunately, Putin have-- developing new program of these chemical weapon, which is forbidden.

Lesley Stahl: The Russians have said that they destroyed all these chemical weapons.

Alexey Navalny: That's why, actually, they deny everything. Because it means that they still have this Novichok. So it means they're not just violating with keeping it. They are continue to improve it.

Lesley Stahl: And there's no doubt that Russia is the only place where that could have come from?

Alexey Navalny: This is absolutely correct.

Lesley Stahl: It's a banned substance.

Alexey Navalny: It's a banned substance. I think for Putin-- why-- he's using this chemical weapon to do-- do both, kill me and, you know, terrify others. It's something really scary, where the people just drop dead without-- there are no gun. There are no shots and in a couple of hours, you-- you'll be dead and without any traces on your body. It's something terrifying. And Putin is enjoying it.

Lesley Stahl: You have said you think that Mr. Putin's responsible.

Alexey Navalny: I don't think. I'm sure that he is responsible.

Putin spokesman Dmitry Peskov says the charge is "completely baseless and unacceptable."

But Angela Merkle of Germany and Emmanuel Macron of France have persuaded the European Union to impose sanctions over this.

Lesley Stahl: Well, all these leaders have signed on, except Donald Trump. And--

Alexey Navalny: Yes, I-- I have noticed it. (LAUGH)

Lesley Stahl: Is it important to you that he condemn this action?

Alexey Navalny: So, I think it's extremely important that everyone, of course, including and maybe in the first of all, president of United States, to be very against using chemical weapons in the 21st Century.

But why would Putin want to poison Alexey Navalny? When we first met Navalny three years ago, he was running against Putin for president. He had made a name for himself by getting his hands on incriminating internal financial documents related to high-level officials and posting them on a blog.

Lesley Stahl in 2017 interview: Did these documents that you got prove corruption?

Alexey Navalny in 2017 interview: Absolutely. I work as a whistleblower. And I'm not afraid to announce the names.

He says he found that the Kremlin's inner circle was accumulating vast amounts of wealth and published pictures of multiple homes and yachts. He moved on to airing documentaries on YouTube, with video of the officials' lavish lifestyle.

Alexey Navalny: And it's-- it's something very special about Mr. Putin, that he's crazy about money. Personal money, about his family being rich. His friends, like, all his people who-- was-- served hi-- with him-- with him in the KGB, all of them, they are billionaires. That's why fighting corruption means for him that he's fighting me.

Lesley Stahl: You know, I'm smiling because here you are. You have survived the most potent nerve agent there is, and you are as fiery and worked up about your-- about Putin and what's going on in this country as you were when I met you a couple years ago.

Alexey Navalny: Well, I'm glad. (LAUGH) I'm glad that I survived.

His blog enflamed so much outrage in 2017 that tens of thousands of Russians took to the streets against Putin. When Navalny called for a second round of protests three months later. He was arrested before he even left his apartment building. He's been jailed so many times, he's lost count. He's been beaten, had green dye with acid splashed in his face and now he can add poisoning to his resume and blame President Putin.

Lesley Stahl: Now how can you say that? Why wouldn't it be one of the oligarchs whom you've embarrassed by, as you say, exposing their corruption?

Alexey Navalny: Even for an oligarch, it's impossible to get this Novichok. It's not something you can buy in the store even if you have millions of the-- billions of dollars. Maybe more important, you cannot use it. You will kill yourself and everyone around. Because it's very difficult to, you know...

Lesley Stahl: Contain it. Yes, yes--

Alexey Navalny: Yes. And then this huge cover-up operation. There is no criminal investigation so far. If-- if Putin is not responsible, why there is no investigation? And look, what they're doing right now. Like-- Putin with a conversation with the French President Macron, he said, "Well, Navalny poisoned himself." Seriously?

Lesley Stahl: Mr. Putin told the President of France that you poisoned yourself--

Alexey Navalny: Yes. It was just to, you know, annoy him.

Putin is contending with rounds of protests in the far eastern part of the country with people taking to the streets for the past three months. Navalny thinks the attempt on his life is connected.

Alexey Navalny: Despite his controlling police, judges, courts, media, and everything, still he's-- like-- he understands that he is surrounded by protest. And it's increasing. So that's why his-- they decided to, you know-- extreme measures.

This is what he looked like just a month ago, soon after his doctors brought him out of an induced coma. Rail thin, with a sickly pallor. This photo was taken the first day he saw his children after being taken off a ventilator.

Lesley Stahl: So you were in a coma. And then you woke up and what happened?

Alexey Navalny: After this coma, I just jump to the long period of kind of crazy hallucinations. And several, you know, steps of realizing where I am, who I am. I could not speak and I could not write.

Lesley Stahl: Well, how has this affected your family?

Alexey Navalny: Well, it was a difficult situation. But they stand it.

Lesley Stahl: Including your children?

Alexey Navalny: Including children--

Lesley Stahl: You have-- your son is 12 and your daughter is in college.

Alexey Navalny: Right.

Lesley Stahl: Those are tough ages to realize that your father came close to being assassinated. Did they say to you, "Pop, Dad, you have to stop."

Alexey Navalny: Absolutely not. No. Absolutely not. My-- I am very lucky man because I have all support from my family.

Lesley Stahl: You'd almost have to at this point.

Alexey Navalny: Yeah.

Navalny, his wife, his bodyguard and I went out for a walk in front of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin and a phalanx of police showed up.

Lesley Stahl: You certainly travel with a lot of protection.

Alexey Navalny: Yes, I have a lot of security.

He is under the protection of the German government because there's concern he could be the target of another poisoning. And yet, he said he's determined to return to Moscow in a couple of months as soon as he is 100% and resume his work where he left off campaigning against Vladimir Putin.

Lesley Stahl: You know, you used to be known as the man who had no fear. But what about your family? Do you ever think-- that you are you're putting them in danger?

Alexey Navalny: That is a toughest part, yes. I don't feel any fear, but children. What is kind of really a horrible thought, if they will try to use this Novichok somewhere around my apartment where my children is come. And, like, you know, this door or something, but everyone can touch it. Well-- (SIGH) but anyway, we should fight these people because they will never stop. They will poison someone else. They will poison more people.

Lesley Stahl: Well, how do you feel now? Are you back? Totally back? You seem to be.

Alexey Navalny: I still need some time to recover. And I'm working on it.

Lesley Stahl: But you do go to rehab. Do you go every day?

Alexey Navalny: Yes, to learn from the scratch how to move, how to do some things. They-- interesting that-- I feel kind of a bit of wooden or tin man, like from "The Wizard of Oz" because the body lost all flexibility at all. Interesting how it's work. I have no idea. It's-- now it's-- difficult move is for me, for example, pick something from the ground.

Lesley Stahl: What about the psychological effect of having-- knowing that somebody tried to kill you, came that close?

Alexey Navalny: You know, I think it's a good thing. It's very useful for politician, maybe facing death once, because it's-- change you a bit. So maybe ironically, I became kind of more human after this, facing death.

The Biden administration's national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, on CNN last Sunday, warned the Kremlin of "consequences," if Alexey Navalny dies in custody.

Produced by E. Alexandra Poolos. Associate producers, Kate Morris, Collette Richards and Anna Noryskiewicz. Broadcast associate, Wren Woodson. Edited by Peter M. Berman.