50th anniversary of Medgar Evers' broadcasting milestone

(CBS News) JACKSON, Miss. - In the early 1960s, as Medgar Evers was becoming better known nationally as a civil rights leader in Mississippi, he found himself shut out of local television newscasts in his hometown and the state capital, Jackson.

Although Evers served as the field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, local TV and radio stations never called, his wife, Myrlie, recalled in an interview.

Coverage of civil rights demonstrators was rarely seen on local stations' like Jackson's dominant Channel 3, WLBT. She said Medgar's press releases were often wired to NAACP headquarters in New York so it could get information before interested national media. At home, her TV screen would sometimes go dark when black entertainers like Sammy Davis Jr. or Lena Horne came on.

"So, we were blocked from seeing successful people of our own race appear anywhere. I can recall my eldest son saying to me, 'Mommy, the television's broken again,'" Myrlie said. "It was a form of suppression."

As the civil rights movement grew across the South, on WLBT only the segregationist point of view was regularly heard, such as on programs sponsored by the White Citizen's Council. Starting with the Little Rock school desegregation crisis in 1957 and continuing for six years, Evers wrote letters to the station pleading for equal time. But he was turned down repeatedly by station manager Fred Beard.

"He was a militant segregationist. He was deeply, ideologically involved in maintaining white supremacy in the South," said former Mississippi Gov. William Winter, who went to the University of Mississippi with Beard.

Winter, now 90, estimates that 99 percent of white Mississippians were segregationists at the time, and admits that he was one too. Winter had served in the state legislature and ran and lost for governor in 1967.

"On local TV and in the local media, the print media, it was a one-sided story all the way," Winter said.

Evers described the news blackout as a "cotton curtain" that enabled racial atrocities to be perpetrated. She said, "There was a desperate need to keep Mississippi's secret...secret."

Myrlie and Medgar, both native Mississippians, met at historically black Alcorn State University, in Lorman, Miss., during Myrlie Beasley's first day on campus. At 18, she was married to Medgar, and at 30, she was a widowed mother of three.

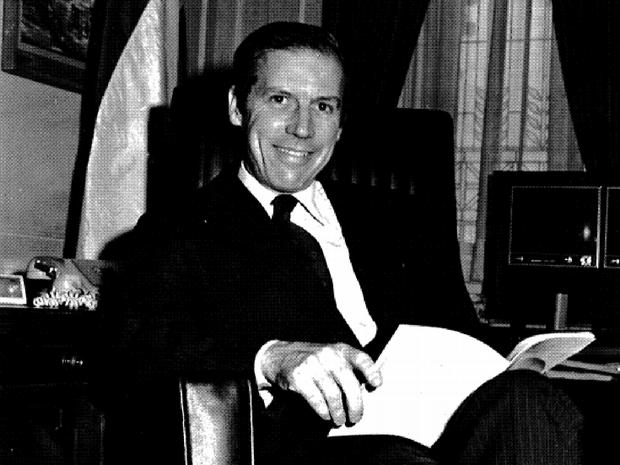

Medgar Evers is enshrined in history books for his courageous efforts to register blacks to vote, desegregate schools and boycott white merchants who wouldn't serve blacks, but his breakthrough on the airwaves is less well known.

In the spring of 1963, following the successful civil rights campaign in Birmingham, Alabama, Evers and the NAACP sued the city of Jackson to desegregate its public elementary and high schools, and he called for equal access to public accommodations and city jobs.

On WLBT, Jackson Mayor Allen Thompson rejected the idea of a biracial committee to study change and criticized the NAACP as "outside agitators."

Finally, Evers was granted time to respond, on May 20, 1963. He spoke for 17 minutes, beginning by telling his audience he was as an U.S. Army veteran who fought fascism and Nazism in Europe during World War II. He talked about a 40 percent black city of 150,000 residents that had no black police officers, firefighters, or clerks. He called for a black man being able to "register and vote without special handicaps imposed on him" and "more jobs above the menial level in stores where he spends his money."

Evers said toward the end: "The two races have lived here together. The Negro has been here in America since 1619, a total of 344 years. He is not going anywhere else; this country is his home. He wants to do his part to help make his city, state, and nation a better place for everyone, regardless of color and race. Let me appeal to the consciences of many silent, responsible citizens of the white community who know that a victory for democracy in Jackson will be a victory for democracy everywhere."

Tape recordings of viewer calls to WLBT, preserved at the Mississippi Department of Archives and History vividly depict the irate reactions of many white viewers who laced their comments with racist epithets.

"There was support in the white community, but it was very low key and very quiet," Myrlie Evers said. She believes her husband's groundbreaking speech made him a more visible target.

"If you challenged any tradition, certainly in Mississippi, your life was on the line," she said.

The next several weeks saw a fury of civil rights demonstrations in Jackson, including lunch counter sit-ins at a Woolworths that met violent resistance.

Less than one month after Evers' appearance on WLBT, he was assassinated, the very night President John Kennedy gave a nationally televised speech promoting his civil rights agenda. On June 12, 1963, after pulling his car into his driveway, Evers was struck in the back by a single rifle bullet fired from the bushes across the street. His wife and children were inside the home and heard the fatal shot.

Myrlie said, "I could never get his blood up off of the concrete. My eldest son stopped eating. He would take a toy rifle with him to bed. My daughter would go to bed holding a large picture of her dad. Our youngest, who was three, just had this sad look. Those children suffered, because they saw their father shot down. They saw him bleeding; they saw him die."

Evers was only 37. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. By then, President Kennedy had engaged in direct negotiations with Mayor Thompson, and Jackson had sworn in its first black policeman.

It took three trials over three decades to convict Evers' killer, Byron De La Beckwith, who died while serving life in prison in 2001.

Today, the National Archives in College Park, Md., retains the records of Evers' quest for equal time. It became a years-long legal battle that ultimately forced the Federal Communications Commission to revoke WLBT's license and award it to new owners who shared Evers' vision.

"I wish Medgar had lived to see and participate in that, but he didn't," Myrlie said. "We broke barriers, and more people of color did away with their fear and joined in the movement to crush -- crush -- segregation."

William Winter served as Mississippi's governor from 1980 to 1984, focusing on education reform and sending his daughters to integrated schools. Since his retirement from politics, he has opened an institute for racial reconciliation. Winter never met Medgar Evers but is an admirer.

"He was the man on the horse out there leading the charge and gave courage and encouragement and support of people who largely had been without hope," Winter said.

In Jackson, the airport is now named after Medgar Wylie Evers, which has a permanent exhibit detailing his contributions to historic change.

Myrlie was married again for 18 years to Walter Edward Williams, who died in the mid-1990s right before she became the NAACP's chairman of the board for one term.

"It was critically important to have the airwaves open to all people, so all issues, pro or con, could be discussed, and he felt that something positive would come from it," she said. "There was a sense of movement, that we were moving forward."